My Prediction: Netflix and YouTube will balk at restrictive CanCon rules

In the face of confusing new legislation, streaming companies and influencers will take their business elsewhere

Share

Michael Geist is a law professor at the University of Ottawa and the Canada Research Chair in internet and e-commerce law.

My specialty is the intersection between law, technology and policy. This work has brought me to the centre of a wide range of Canadian legislative proposals and digital policies, including internet streaming regulation. For many years, the government took a relatively hands-off approach to internet regulation, but that changed with the introduction of Bill C-10 in 2020, which was later reintroduced with amendments as Bill C-11.

The stated objective of Bill C-11 is to bring large streaming services, like Netflix, Disney+ and Amazon Prime, into the Canadian broadcasting world. The language used in the bill is so broad that its parameters are subject to interpretation, which leads to a great deal of confusion about what it will do in practice. One concern is that the law opens the door to rules that make CanCon more prominent on streaming services and forces the services to make financial contributions to CanCon, just as conventional broadcasters such as CTV and Global are obligated to do. The bill is under study by the Senate and will likely pass imminently.

RELATED: Why YouTubers like me oppose Bill C-11

The plan to promote homegrown video is all well and good. The problem is what counts as CanCon. And that depends on an outdated—and inherently flawed—government points system. One example is the Netflix-funded film Jusqu’au déclin, which features a Quebec-based story, producer and cast. Everything is Canadian, but Netflix owns the intellectual property, so it doesn’t count as CanCon. Other iconic Canadian stories such as Turning Red and The Handmaid’s Tale have also failed to meet the standard. Companies like Netflix might object to being accountable to such a defective system. The bill also poses problems for Canadians who post videos and other creative content on services like YouTube and TikTok.

My interpretation is that the new legislation will lead to regulation of user-generated content, despite the government’s claim to the contrary. The bill’s broad language could require YouTube and TikTok to identify what is Canadian and prioritize this content in user feeds. Canadian digital creators may not meet the official definition of CanCon and be deprioritized within Canada. Even if they do meet the definition, they face being deprioritized outside of Canada. That’s because services like YouTube use algorithms to determine what users like based on what they click, what they don’t and how long they watch a video. If the CRTC effectively forces companies to promote Canadian videos to people who might not be interested in them, the algorithm will interpret that lack of interest as proof that the content is lacklustre. It may then be downgraded in the rest of the world, which is where creators generate the overwhelming majority—typically more than 90 per cent—of their audience and revenue. Creators could simply pack up and leave Canada altogether to avoid this fate.

In 2023, the CRTC will likely conduct a series of hearings to flesh out the ambiguity in the legislation. Streaming companies and individual creators will come before the CRTC to discuss a wide range of issues, like the definition of CanCon and whether and how user content gets regulated. Services like Netflix will find themselves in a morass of regulatory uncertainty and face the possibility that their investments won’t meet the requirements. Which is a problem, because Netflix pumps billions of dollars into film and television production and content licensing in Canada; it spends more on dramatic film and television production in Canada than any Canadian broadcaster. It’s wishful thinking to imagine that a company will say, “Okay, no problem, we’ll put another billion into Canada while we wait to see how this plays out,” especially in a tough economic climate. Meanwhile, smaller, more niche streaming services may also look at the Canadian marketplace and decide that it’s become too expensive to adhere to the regulations and instead simply exit altogether.

There is still time to fix this bill. Removing user content from its purview would help. And we need to get the definition of CanCon right. A better way of determining what qualifies as CanCon is to look at whether the original source material is from Canada and to treat IP ownership as one of many potential elements to consider, rather than a mandatory requirement. If the goal of the legislation is to increase the production of CanCon, then surely we need a modernized definition of what CanCon is.

—As told to Liza Agrba

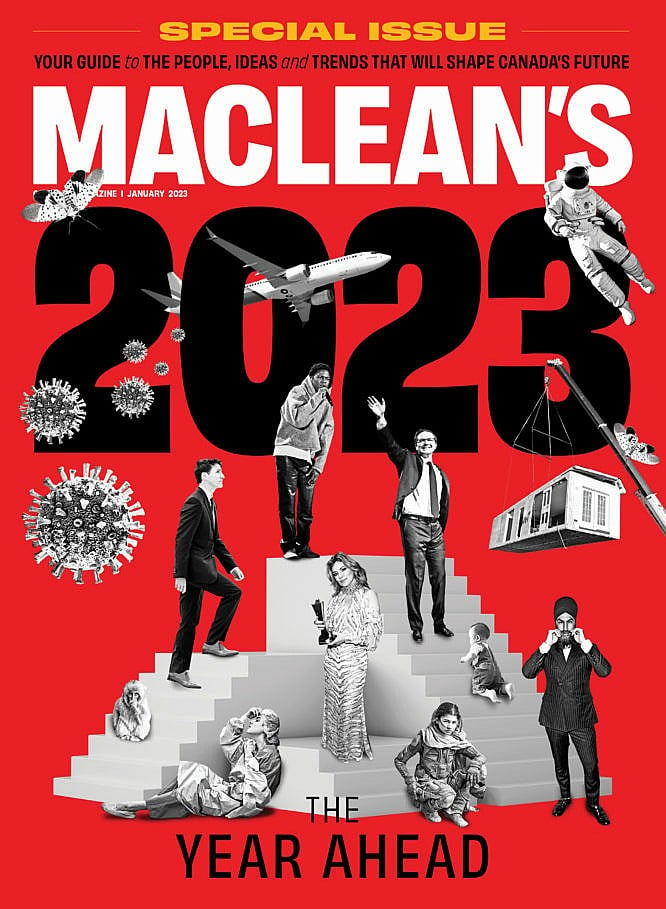

This story is part of our annual “Year Ahead” package. Read the rest of our predictions for 2023 here.

This article appears in print in the January 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.