My Prediction: Downtowns won’t recover from their pandemic slumps—yet

The future is bright for post-pandemic cities, but it won’t look like the past

Share

Karen Chapple is a professor of geography and planning, and director of the School of Cities, at the University of Toronto.

In some of Canada’s biggest cities, downtown activity isn’t likely to return to pre-pandemic levels in 2023. My recent research used mobile-device usage to measure downtown visits in cities nationwide. I found that Canadian downtowns in general are lagging behind those in the U.S.—and those in Toronto, Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver are doing worst of all. Their challenges include the initial severity of their lockdowns and harsh weather, which makes people less inclined to come into work unless they really have to.

One of the biggest problems, however, is that cities like these rely heavily on professional services such as law, accounting and management consulting. Those are businesses in which workers don’t need to be together to be productive. That means transit usage will remain lower, restaurants that catered to downtown workers will continue to struggle, and many office towers will stay empty. If a downtown economy has a lot of that kind of specialization, it’s not going to recover as quickly, since more people can work from home—and the work-from-home phenomenon is here to stay. According to Stanford researcher Nick Bloom, it will ultimately settle at about 30 per cent of hours spent working at home, compared to five per cent before the pandemic.

Luckily, things should improve in the long run. My research showed that in the spring of 2022, Toronto was only at 46 per cent of pre-pandemic activity. If Bloom is right, that should grow to 60 or 70 per cent in 2023 as we settle into the new work-from-home pattern. On the other hand, that’s not 100 per cent, and empty restaurants and office towers will eat away at the city’s tax base. How are we going to fill up that remaining capacity downtown and make it a lively, desirable place to be? Finding the answer to that question is going to take collective action on the part of businesses and cities. One solution is to replace those specialized white-collar sectors downtown with more non-profits, arts organizations, health and education outfits, public administration and so on, where more people are likely to be present at work.

Many downtowns experiencing a stronger recovery have benefited from a lot of new housing. In my analysis, for example, Halifax was the Canadian leader in downtown recovery, at 72 per cent of pre-pandemic activity—thanks partly to an influx of new residents. Many downtowns in smaller cities get a boost from having bigger, family-sized apartments or single-family housing near downtown. Cities like Toronto, with a large share of bachelor apartments, are at a disadvantage, since that housing stock doesn’t work for households where multiple people need to be on Zoom at the same time.

The residential sector can’t save all downtowns all by itself. In cities like Toronto and New York, many people are not using downtown housing units as their main residence, or they have a second home, like a cottage. This means thousands of units are empty most of the year. If we keep more residential units occupied year-round by building affordable and student housing, that’s part of the puzzle.

Transit will also play a big role. In cities like Toronto, which rely more on streetcars and subways and have longer commute times, people will be less willing to come back. You might think that the solution is to make the city more car-friendly; that’s not the case. You could make parking free and try to get rid of gridlock by prioritizing traffic flow, but you would still have so much congestion in the region at large that you’re not going to solve long commutes. New transit projects that are under construction in Toronto—new streetcar and subway lines, and more dedicated lanes for buses—will be a key part of making the city thrive again. Even so, people with 90-minute commutes probably won’t be coming back to the office unless they have to.

We’re also in a worsening part of the economic cycle, facing slower growth. Somewhere like Quebec City could be fully recovered relatively soon because of its robust tourism sector. But other places with more specialized economies, like Toronto, are stuck, at least for a while longer.

—As Told To Liza Agrba

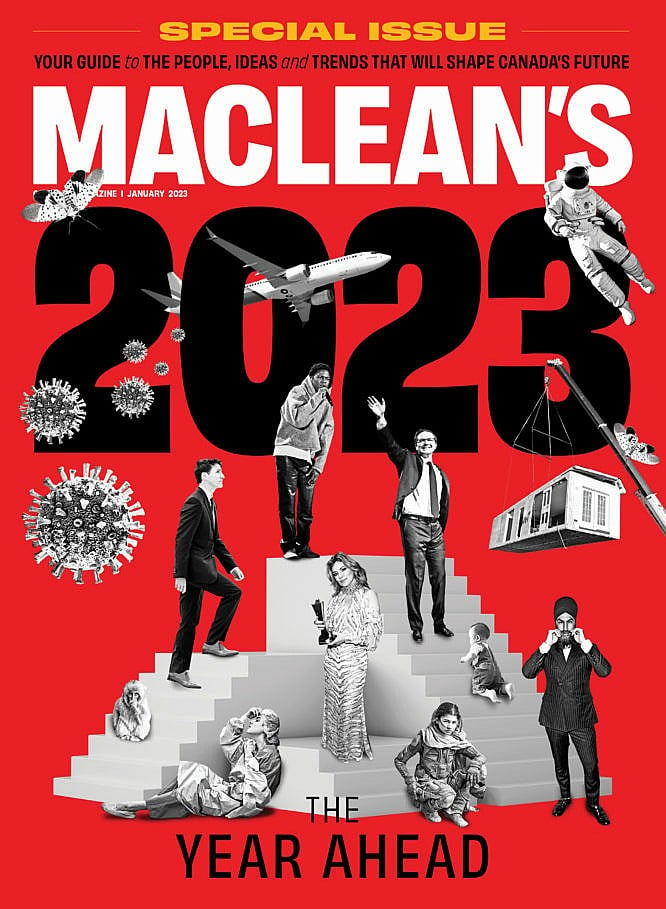

This story is part of our annual “Year Ahead” package. Read the rest of our predictions for 2023 here.

This article appears in print in the December 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.