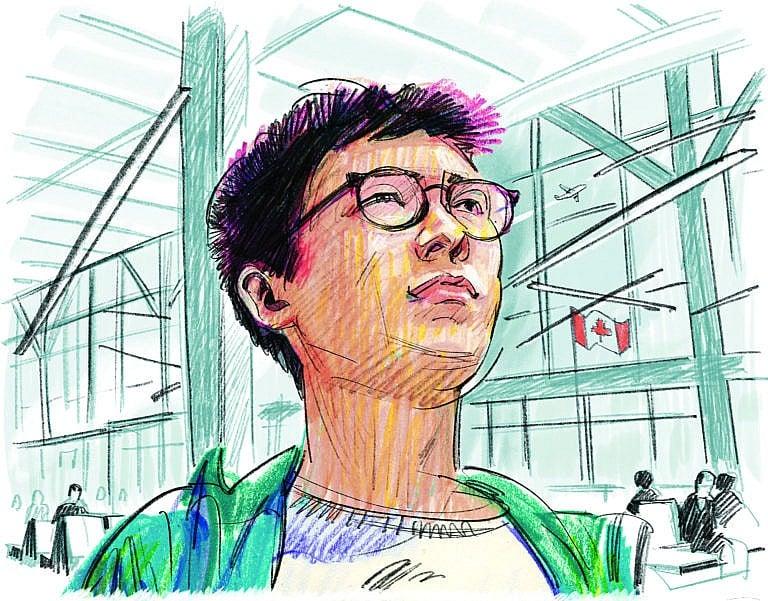

“I was almost arrested for my activism in Hong Kong. I fled to Vancouver for refuge.”

I can see a life for myself here, but I still miss the city where I grew up

Share

I was born in Hong Kong in 1994, back when it was still a British colony. When I was three years old, Britain returned the region to China; the countries agreed that Hong Kong would govern itself and operate as China’s special administrative region for 50 years.

And yet, over the past decade, Hong Kong’s independence has waned. In 2014, China started unrolling rules that declared only candidates nominated by Beijing’s central government could run in legislative and district council elections. This meant our elections would be just for show—and it was unacceptable to me and many other Hong Kongers. I joined hundreds of thousands of demonstrators who held a mostly peaceful occupation in the streets. It gave me a sense of purpose: our protest was a meaningful way to make the government listen to the people.

After I graduated in 2017 from the computer science program at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, I worked as a programmer for a software company and continued my activism work online. Later, I became a labour union executive, advocating for democratic, labour and human rights in Hong Kong. When the government forced civil servants to sign a declaration upholding the authority of Beijing and the Hong Kong government, we felt it interfered with the political neutrality that civil servants should have. To campaign for change, we requested meetings with government officials, but we were ignored.

READ: Thirteen years ago, I left St. Lucia to work in Ontario. I don’t know when my family can join me.

In 2020, Beijing imposed national security laws that would allow the extradition of Hong Kongers to mainland China. I was scared—and angry. The laws were unclear. Officials could use them to punish anybody who committed an act of secession or said something bad about the government. The following year, a Beijing-controlled publication ran articles about our union that called for the police to arrest me and my colleagues, labelling us criminals for being pro-democracy. I knew then I had to leave. With little time to prepare, I packed only the necessary items, secured a tourist visa for Canada and bought a one-way ticket to Vancouver; I’d heard it was a multicultural and welcoming place for newcomers. The week before I left was the Mid-Autumn Festival, a harvest festival in the lunar calendar. It was a well-timed excuse to gather my close friends and family, eat good food and enjoy our remaining time together under the moonlight.

I cried a lot on the day of my flight. I didn’t want to leave the only home I’d ever known, and I wasn’t sure when I would see my family and friends again. But when I landed, I felt relieved—finally, I didn’t have to worry about getting arrested or extradited. With the help of a friend from Hong Kong, I found a room for $1,000 a month in Richmond. Once settled, I applied for an open work permit and explored the area. I came across restaurants serving Hong Kong cuisine, like fried squid and sweet-and-sour pork. I talked to the staff in Cantonese, which helped me feel at home.

READ: “I always felt uncertain about my future in the U.K. I finally found my home in Calgary.”

By January of 2022, I received my open work permit and found a job as a sales representative at a nearby mobile store. I researched permanent residency pathways and discovered that Canada had two options for Hong Kongers: Stream A applicants needed a post-secondary degree from a Canadian school, and Stream B required 12 months of full-time Canadian work experience, plus a post-secondary degree from the past three years. My graduation date just missed the cut-off.

It was hard to sleep at night because I felt so anxious about my future. I could only stay here for three years with my permit, and I helped lobbied MPs to reform this policy. Finally, in July of 2023, during a push to expand immigration, the government relaxed the rules. Now, Hong Kongers with a post-secondary degree from the past 10 years are eligible for Stream B. Hearing the news was a relief—I was happy to finally see a life for myself in Canada.

Early next year, I will apply for permanent residency, and my plan is to find work as a computer programmer in Vancouver. In the meantime, I still do what I can for my people and participate in local protests supporting Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. I want to visit my city again, but I don’t know if or when that will happen. I just have to keep hope.

This article appears in the December 2023 print issue of Maclean’s magazine. You can purchase the issue here, or become a Maclean’s subscriber here.