Gord Downie’s ‘Introduce Yerself’: What makes his last album so brave

Gord Downie’s ‘Introduce Yerself’ is the latest album by a dying musician to stare down death. But what insight do such works really provide?

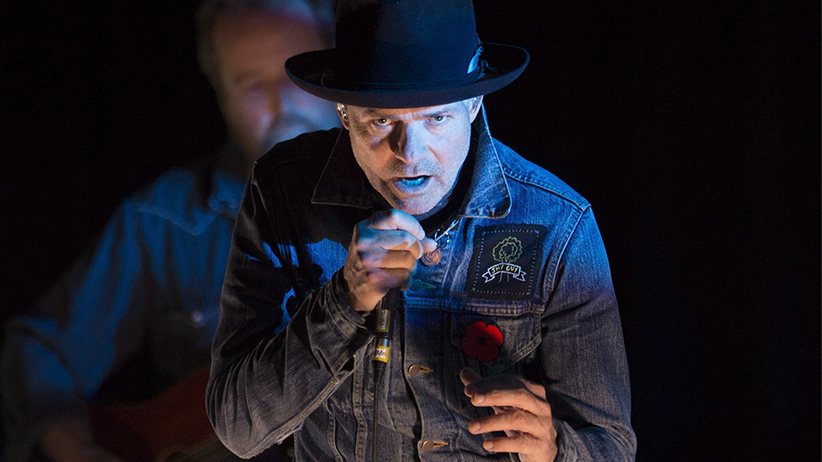

Gord Downie is seen performing part of his solo project, ‘Secret Path’ at the National Arts Centre, in Ottawa. The album is a collection of songs which tell the story of Chanie Wenjack, who died fleeing a residential school 50 years ago. (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

For his last act, Gord Downie stared into the abyss—and found peace, anyway.

Introduce Yerself, which comes out on Oct. 27, may well be the last solo album from Downie, the Tragically Hip frontman who died at 53 on Oct. 17 after a terminal diagnosis of glioblastoma (Hip bandmate Rob Baker told the Toronto Sun that the band has still has “like three albums’ worth” of unreleased music.) It is flush with love: these are delicate songs of excruciating longing, fortified by the sturdy beams of his clarion voice. It begins with “First Person,” a farewell to both an anonymous friend and, in a way, to his own first-person perspective, as he subsumes himself to deliver a series of specific, second-person love letters to his friends and family. Some songs lilt and soar, others are dulcet lullabies, others still are keening and spectral—but for an artist whose omnivorous solo music has flirted with all manner of genres, it’s perhaps a surprise that Introduce Yerself is so sonically similar to the simple piano-and-guitar arrangements of Downie’s previous album, Secret Path.

The album is a remarkable final coup from the singer-poet from Kingston, Ont. But he’s hardly the only musician to stare down death’s approach by taking to their craft, marshalling a lifetime of wisdom to produce a culmination of their artistic legacy, or to turn their suffering into some kind of catharsis.

Under the shadow of terminal cancer, Warren Zevon crafted The Wind, a heartbreaking meditation on dying, capped by his choked-up biddings to “Keep Me In Your Heart.” The hip-hop producer J Dilla worked on his soulful, haunting album Donuts—which is almost Buddhist in how, as the album ends, it loops perfectly back into the first song—as he lay dying in the hospital of a rare blood disorder. Jazz musician Billy Strayhorn’s final arrangement, “Blood Count,” was completed on his deathbed, and the recording by his collaborator Duke Ellington has some of the saddest swing ever put on wax. David Bowie knew he didn’t have long before liver cancer claimed him, and he set to work on a career monument, Blackstar; even though he was reportedly planning one last album to follow it, he died just two days after its release, and it sounds every bit like a last musical will and testament all the same. “His death was no different from his life—a work of art,” Blackstar producer Tony Visconti wrote in a Facebook post after Bowie’s passing. “He made Blackstar for us, his parting gift.”

SPECIAL ISSUE: Maclean’s commemorates the life and legacy of Gord Downie, 1964-2017

By and large, these are beloved albums, with listeners gripped by the insight offered by those at death’s door. But they elide the cruel fact that death is never so neat. Most people do not have a sense of when their day will come, and even when they do, it is often in the face of the wild unknowable, or at the end of a period of unjust pain. And music, ironically, may actually be an inadequate medium for the task: its chords often resolve, a song’s minor falls and major lifts culminating then fading out; its rhymes are clean and rounded, as reliable choruses wrap familiarly around verses; a song usually clocks in as a taut, three- or four-minute unit, an album a parcel of concepts.

Death is messy and hard. And yet we find ourselves craving the lie that reconciliation awaits for us, anyway—and these albums, beautifully or not, are willing to give it to us.

“You can’t shoehorn a universal [interpretation] onto them because death is such a unique experience for every person, whether they know it’s coming or it’s sudden,” says Jordan Ferguson, a Toronto-based freelance writer and the author of a book on J. Dilla’s Donuts for the 33 1/3 series. “But we want the creative summation, we want the final statement. We want to hear that the person was okay with it, so that we’re made to feel okay with it.”

The thematic familiarity of these kinds of works—elegiac albums about a peaceful coming-to-terms with death—sits at loggerheads with what the intellectual and writer Edward Said notes in his 2007 book On Late Style: that a distinctive artistic “late style” emerges from a dying master boldly confronting an accepted norm of either society or the artist’s own past work. “The artist who is fully in command of his medium nevertheless abandons communication with the established social order of which he is a part and achieves a contradictory, alienated relationship with it,” he writes. (Said produced the book as he himself was dying of leukemia.)

Take Wolfgang Mozart’s opera Cosi fan tutte, for example. It’s one of the composer’s final works, and it keeps with operatic tropes in its frivolous narrative about two men who disguise themselves in a plot to woo each other’s partners—but with its void-like amorality of its key players, disproportionately beautiful music, and an ending that leaves the traditional happy return to normal ambiguous, it shows us “a universe shorn of any redemptive or palliative scheme … and whose only conclusion is the terminal repose provided by death.” Ludwig van Beethoven’s late period featured some of his most difficult and dissonant work which, despite being lauded today, was referred to by one contemporary as a series of “indecipherable, uncorrected horrors.” And, more recently, Frank Zappa—dying of prostate cancer—spent his final years working on the compositions that appeared on The Yellow Shark, an album of experimental orchestral music that broke with the tradition of his earlier, more antic output. These works, in many ways, may be truer reflections on death as it actually feels: they are challenging, abrupt, fractures against the grain.

But still, there’s something radical and confrontational about artists in their twilight simply making music at all—a refusal to back down from the often unseen torments of dying, even if they’re packaged as soothing false promises. “Dilla’s knuckles were stiffened and his hands were swollen; for a guy who had to tap out beats on samplers, that becomes problematic,” says Ferguson. “The tools at your disposal become more limited, so you have fewer means to express the things you want to express.” Indeed, as Terry Teachout wrote in a 2009 Wall Street Journal essay, “when creative artists … do manage to eke out enough energy to make art in the face of death, their creations are almost always modest in scale, if not in significance.” They do not owe us their last works, but they do it anyway, even if they are diminished—an act that makes the gift all the more remarkable. No matter how it sounds or what it says, any art made at dusk still counts as an act of rage against the dying of the light—so this art breaks from the normal just by being made.

As for Downie, who reportedly started work on Introduce Yerself in January of 2016—not long after emergency surgery to remove some brain-tumour mass, and while he was undergoing painful daily radiation treatments—his own late style may also be defined by his confrontation with Canada’s relationship with First Nations, the cause he devoted his last months to. It’s in the way that Secret Path and the Hip’s final tour tackled Indigenous issues; it’s in this album’s final song, “The North,” which weaves together the insight we crave with an advocacy for an issue “that is over 100 years old,” as Downie sings—one that many might find challenging, abrupt, a fracture against the grain. “Turn our faces to the sun,” he growls as the album’s final words, a last plea to the living, “and get whatever warmth there is.”

There may not be any bold stylistic moves introduced in Introduce Yerself. But it will fracture your heart all the same.

MORE ABOUT GORD DOWNIE:

- ‘No dress rehearsal, this is our life:’ Gord Downie and the Canadian conversation

- Remembering Gord Downie, Kingston’s king

- Powerful Gord Downie memorial fills Kingston’s Springer Market Square with light and lyrics

- Remembering Gord Downie through his lyrics

- Gord Downie memorial: Fans in Kingston belt ‘Ahead by a Century’

- Gord Downie: Watch a special, two-hour tribute

- Tearful Trudeau makes emotional statement about Gord Downie’s death

- Gord Downie remembered: Tributes to the Tragically Hip frontman