How an exhibit of protest art wound up sparking a protest of its own

A Toronto resistance-art exhibit has raised a furor—and a renewed debate over what’s artistic appropriation and what’s in the public domain

Share

A recently launched exhibition at Toronto’s Power Plant art gallery has shed light on the tangled subject of backlash—though not quite in the way it intended.

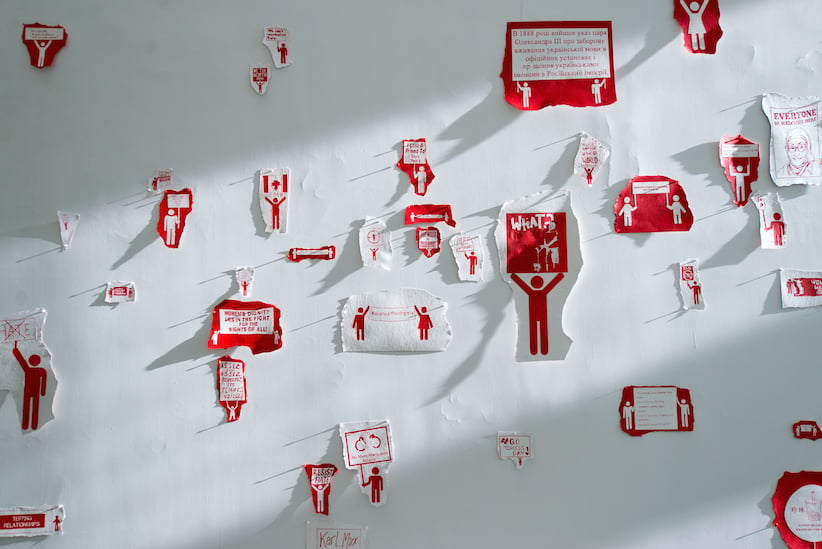

Demonstration, commissioned under the Power Plant’s Fleck Clerestory program, showcases images selected from a body of public submissions. Last summer, the gallery put out an open call for images of protest art that people had come across in their daily lives—affixed to telephone poles, for example, or held up at rallies. Alongside a team of eight Power Plant drawing assistants, Michael Landy—the British artist and member of London’s Royal Academy of Arts who received the Power Plant commission—reproduced selections of his choosing in a uniform red-and-white oil paint style. Landy is known for his destructive artistic confrontations of consumerism. The reproductions, displayed on two opposing walls, follow the theme of the artist’s Breaking News exhibition in Athens earlier this year, for which the local public also sent in submissions. (Landy reproduced those in blue.) Together, the walls make up what Landy calls “a wall of protest”; the pieces featured range across various social issues and levels of seriousness, from “Slut Pride” and “Make Hummus Not War” to “Solidarity With Standing Rock” and “Stop Islamaphobia”.

“It’s meant to open up some kind of channel of engagement in Toronto,” says Landy, in an interview with Maclean’s. “…They can be small ideas, big ideas. It’s a demonstration: people can be angry or sad. There are no rules, it’s just whatever people want to send in.”

At a moment when many people are becoming political in an atmosphere where protest is once again becoming mainstream, it is understandable that a gallery would use its space to discuss the power and prevalence of protest art. As the Power Plant puts it, the hope was to see “Canada’s social and political landscape through the eyes of its inhabitants.” Most would not dispute the ethos in theory: after all, the point of any public display is that it be seen, its message considered by as large an audience as possible. Having these pieces appear in a prominent gallery extends the latitude of protest.

But the execution, from the gathering process to the curation, has proven controversial. Some of the artists whose work was reproduced—many of whom work and live as activists, very close to the poverty line—have accused Landy of stealing their work, as the exhibition does not credit the original artists. The work has reignited a debate over whether the spirit of activist art can remain genuine when it is reproduced for spectacle—and to whom art in the public domain belongs.

“Where is the Power Plant when Black Lives Matter are protesting?” asks Lido Pimienta, a multi-disciplinary artist who won Canada’s Polaris Music Prize last month. “Where is the Power Plant when we’re walking for missing and murdered Indigenous women? That’s the issue. It’s so lazy to say that this is resistance… It’s a decoration to them. Am I supposed to be honoured?”

One of Pimienta’s posters, created in support of Black Lives Matter, appears as a reproduction in the gallery. The Power Plant’s version replicates the style of her other artwork and would be recognizable to those familiar with her practice. She feels that the gallery should have taken measures to compensate and credit the original artists. At the very least, she says, an attempt should have been made to inform the creators of their works’ inclusion.

“In no context is it acceptable to use artwork without permission,” says Pimienta.

Some feel that Landy’s paintings were arranged antithetically to the principle of the art itself. In each painting, for example, the slogan featured is held up by an icon symbolizing a male or female body, similar to that of bathroom signage. While the intention was likely to reiterate that these signs were once held up by people at protests, the pants-versus-skirt distinction reinforces a gender binary—even though the gender binary is among the subjects being challenged.

“The Power Plant has created a context to contain radical messages, and to make sure that their bourgeois patrons don’t have to think too hard about their complicity in various injustices,” says an artist who unknowingly had a reproduction appear in the exhibition, and who asked to remain anonymous for this story. “It’s insulting to see my slogans divorced from their images, sharing wall space with total apolitical garbage and knowing that Michael Landy is getting a cheque for defanging my political speech. An institution that takes money from RBC, who bankrolls tar sands expansion…could never display my artwork by a method other than theft. My work is anti-colonial.” (The Royal Bank of Canada funds a curatorial fellowship at the gallery, and for Demonstration, Landy worked alongside Nabila Abdel Nabi, the RBC curatorial fellow.)

Landy’s British identity, too, is a point of contention. Given the exhibition’s proximity to Canada 150, and how much art featured therein addresses the subject of colonialism in Canada, Pimienta notes that the exhibition ignores how it is mirroring the act of colonialism itself. “Is the intention to show that art can be also be settler colonialism?” asks Pimienta. When the exhibition finishes in May, those who sent in successful submissions will be offered the resulting reproduction, essentially giving participants a free facsimile to take home.

“With money flying at the appropriation prizes and Joseph Boydens of the world, it’s obvious we need venues to put their resources behind thoughtful anti-racist and anti-colonial artwork made by Indigenous people,” says the artist who asked that their name be withheld. “Paying a British artist to co-opt Indigenous voices marks a dismal failure on the part of the Power Plant to address the cultural needs of this country.”

Isaac Murdoch, an Anishinabek artist, was perplexed to learn that a reproduction of his work appeared in the exhibition. Murdoch makes art “for the movement,” he says, and allows people to use his designs for free when rallying for land and water defence. “I openly tell people, ‘if you’re in a crisis situation in your territory, if you’re trying to stop a pipeline, by all means use my work, fundraise and get the funds that are needed.’ My art is for the people to use. If anyone makes a profit off my work, it’s going right into land and water defence,” he says. “…If they’re using my art, I have a lot of questions… My art needs to be on the ground with the people. I’d never want it to be seen in another light. That’s what I like about my art: regular people can go with it to create awareness.”

In this regard, Landy’s exhibition could arguably be achieving what it set out to—uniting protest art with the people. “I was trying to talk to people directly, rather than through the media, in a sense,” he says. “…I was interested in asking people where they’re at in this particular point in time. That’s what really frames it. It’s a snapshot of Canadian life today, a small segment of the thoughts and feelings of people who live in Canada.”

When asked about the criticisms surrounding his exhibition, Landy offers few words. During his interview with Maclean’s, the Power Plant’s marketing and communications officer Nadia Yau jumps in to clarify that submissions are “photographs of things that already exist in the public sphere and are part of the public dialogue.” Yau mentions that anything reproduced for the exhibition could just have easily appeared in a newspaper or blog post.

“The placards are in the public domain already,” says Landy, referring to protest signs. “It’s not like I’m going into an art gallery and photographing things and reproducing them…It’s quite hard to take ownership over something that’s in a public demonstration.”

Indeed, some of the original creators of the reproduced pieces would have been difficult to track down given the anonymous nature of the work. In other cases, however, such as that of Pimienta and Murdoch, the designs are recognizable enough that the artist’s identity is not hard to determine.

At the heart of the debate is a discord of artistic ideology. Some see protest as a survival mechanism; others see it as décor. If art is indeed in the tapestry of our lives, who determines the limits of its purpose? The real question, perhaps more importantly, is one of ethics and compensation—how adequate an argument is fair use when artists are struggling to afford to feed themselves?

MORE: Why art galleries are quietly clearing out their vaults to private bidders

Elizabeth Legge, a professor of modern and contemporary art at the University of Toronto and a fan of Landy’s work, recalls reaching out to him years ago, seeking permission to reproduce his work for a project of her own. He told her to go ahead, and use it at no cost. “He wrote back and said, ‘I don’t believe in that kind of thing,’ ” she says. “He had an ideological belief that once the work was out there, it was out there.”

Legge points to the controversy surrounding American photographer Richard Prince’s 2014 Gagosian Gallery exhibition—in which he reappropriated photographs from Instagram and sold them for extravagant fees—as a turning point in the art world’s conversation about inspiration and theft. “The objections of people who feel their work has been taken should be acknowledged,” she says. “It doesn’t hurt anybody to say who the original artist was.” (Prince has been the subject of several lawsuits that claim he used work without permission from the original artist.)

This debate has come up before, too. “Appropriation is the idea that ate the art world,” wrote New York Magazine art critic Jerry Saltz in 2009. “Go to any Chelsea gallery or international biennial and you’ll find it. It’s there in paintings of photographs, photographs of advertising, sculpture with ready-made objects, videos using already-existing film. After its hothouse incubation in the seventies, appropriation breathed important new life into art. This life flowered spectacularly over the decades—even if it’s now close to aesthetic kudzu.”

But “taking images and using them yourself, it is problematic,” says Legge. “The thing that possibly distinguishes this is that the images were functioning anonymously. But there’s always a gulf between legal positions and moral issues.”

Those critical of the exhibition say that the Power Plant missed an opportunity to bridge the gap between local artists and Power Plant-goers. Pimienta, for example, says a panel discussion could have been held to engage artists and the public in dialogue. Legge suggests that an information sheet with additional artist credits could have been (or still could be) distributed to gallery visitors, or that the Power Plant could display artist names at the exhibition’s entrance. Murdoch feels that if the exhibition is really about the people, the gallery should make a donation to charitable organizations that represent issues at the heart of it.

“There’s nothing wrong with gallery art, but the symbols I’ve created, that’s not what they’re for,” he says. “It’s almost like grabbing a sleigh dog that really knows the bush, knows the trapping roots, can read the stars, knows where the thin ice is—and putting it in a fancy dog show. No. That dog needs to be in the bush, doing what it does.”