Remembering Gord Downie, Kingston’s king

Opinion: What the Tragically Hip’s Gord Downie meant to his hometown—a place of contrasts, of potential, and of hope

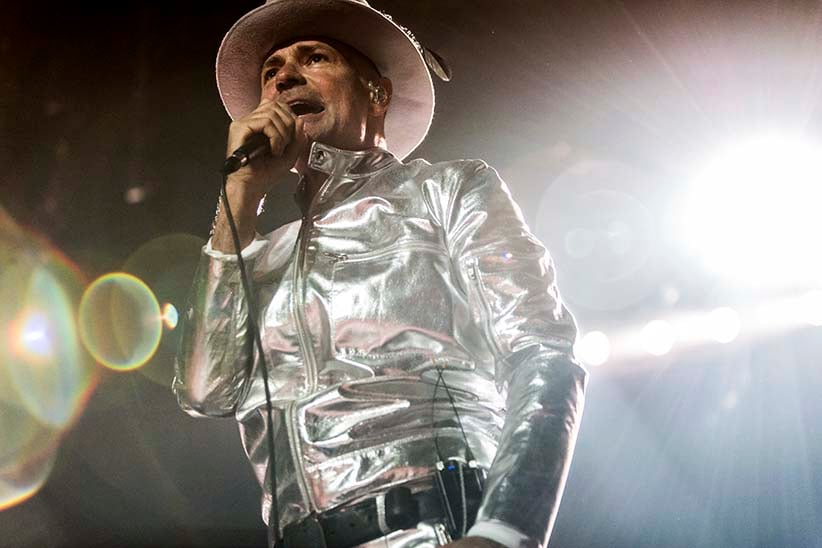

Gord Downie, lead singer for the Tragically Hip, performs during the band’s last concert in Kingston. (David Bastedo/The Tragically Hip)

Share

Luke Ottenhof is a writer living in Toronto who spent his first 18 years in Kingston.

Growing up in Kingston, Ont., isn’t much different from growing up in any other mid-sized city in Canada. The city of roughly 125,000 people is a relatively provincial place, caught in a triangle between Ottawa, Toronto, and Montreal on the coast of Lake Ontario. But each mid-sized city life needs a narrative, and every narrative begs for a soundtrack. Kingston’s is wrought, inextricably, with the sounds of hometown pride Gord Downie and The Tragically Hip.

The same must be true for many millions of lives across Canada during the band’s 30-plus years of existence. But it was Kingston’s narrative and Kingston’s soundtrack first, and for just that reason, Gord and the Hip have always been—and will always remain—the sound of my home.

Whether it was blaring over radio stations like 98.9 The Drive, or cutting through beer-glass clinks on the alleyway patio of the Toucan bar downtown, or humming over chatter between sets at The Mansion on upper Princess, Downie’s voice has been a fixture in Kingston’s daily life for decades. Growing up in the lakeside city, we were reared on a steady diet of folk and Can-rock that trickled into Kingston from the major hubs around us, but it became quickly apparent that Gord was not like Stan Rogers, nor Gordon Lightfoot, nor Stompin’ Tom Connors, nor anyone else. For a quiet city like Kingston, it was a rallying cry, like spark to kindling. Though many Canadian voices passed through the city, Downie rose from within, fiery and virile, to shake the city awake.

OUR OBITUARY: Remembering the life and legacy of Gord Downie

When my cousins and I learned to sing and play guitar, they were Gord’s words that we sang. It didn’t matter that we didn’t know who David Milgaard was, or what Downie meant when he snapped, “Baby eat this chicken slow, pull apart them little bones.” When we were given electric guitars, the only riff we cared to perfect was the shuffle of “New Orleans Is Sinking.” We flocked to Gord’s word like moths to a light.

Our attachment to Downie’s voice grew to become more than an appreciation. It became a fascination: the switchback dynamics from soft and low to soaring hollers, the tortured, disruptive wails, the stuttering delivery, the vibrato that seemed not so much trained as innate, a force of nature that rippled through his heart and mind and burst from his vocal chords, shaking his voice. That voice—and even this descriptor feels disrespectful to Gord—will follow Kingston forever, emboldening a city always seen as lesser and yet striving to be as much as it can possibly be.

Perhaps more than we connected with Downie’s voice, we connected with who he was speaking to: us. The rock radio stations we grew up with in Kingston, as across Canada, were inundated with Americanness: American artists speaking about American people and American places. Bruce Springsteen and Guns N’ Roses sprinted beside each other on the airwaves, speaking in imperial measurements and forging a Canadian town’s culture through explicit Americana. But when we heard Downie speak about a small town in the Kawartha Lakes or a line of longitude in Manitoba or Canada’s capital city, we heard something rooted in reality, not fantasy: We lived there, and someone from Kingston was singing about it. It was a necessary reflection for us; we could identify with and celebrate ourselves, and we could do it on drive-time rock radio. We existed, in an anthemic golden wash of sound that swept across the nation.

The affirmation of identity that Downie gifted to us went right down to the most personal of minutiae. Like most small-ish cities, Kingston doesn’t have a vast number of elementary and secondary school identities to choose from. Unless you’re a star athlete—and despite my best efforts, I was anything but—your social status, which in those days often equated to your humanity, is probably poor. If you existed beyond the bounds of conventional culture in Kingston, you might cease to exist at all. Resources for inclusive counterculture and people who don’t subscribe to hockey-bro aesthetics are vital but sparse. One of the city’s few identifiable spaces for inclusion and progress, the beloved Sleepless Goat, closed its doors last March.

But Downie, draped in a smoky bar-rock mantle, planted a flag for Kingston’s freaks. His lyrics were dense, bordering on esoteric; his voice was manic and intense; his stage presence was confrontational and shocking—but he made it work with a blue-collar blues-rock framework, a meat-and-potatoes crush of guitar crunch and simple rhythms. Downie distorted those conventional machinations, weaving abstract, intellectual narratives and poems overtop of them. He wove a patchwork of critical social theory, bland observations, and high-brow literary references to create something truly original and accessible, painting him as a friend of both the proletariat and the academic. Little wonder he came from Kingston, a study in dichotomies splintered between the university’s teeming student population and the city’s loyal residents. The students have Queen’s; the townies have the Hip.

Sure, there’s the Tragically Hip Way, a road hemming in Kingston’s arena, the Rogers K-Rock Centre. There’s the fact that one can rarely stroll downtown without crossing paths with Hip guitarist Rob Baker, his towering frame and shimmering brown hair feeling as institutional as the city hall itself. Still, though most Kingstonians hardly bat an eye at these signifiers. What’s most remarkable about The Tragically Hip in Kingston is that the band feels as unremarkable as a favourite well-worn shirt or a trusty take-out place; they’re a part of our daily existence, and a cornerstone in our conspicuously cultivated identities. Just as he could be venerated as a working-class everyman, he could be lauded by scholars and poets as an exemplary writer. He was everything to everyone, and so he was an icon for Kingston’s possibilities.

In Kingston, the Tragically Hip are our common cants; when we speak of where we come from, we speak of the Hip. We’re referring to family with whom we jammed “Wheat Kings”; we’re referring to bars that played Downie’s music; we’re referring to car rides with Yer Favourites blasted front-to-back on a CD drive; we’re referring to streets named after the band and venues where they had performed. While I was far away, my homesickness could be assuaged by hearing Downie’s voice on the radio, a quixotic salve for whatever the world could throw my way. It’s my understanding that most Kingstonians have this same coping mechanism. Gord has shown us the power of the human spirit: if Gord, who walked the same streets we do, and he could fight, so can we.

And if you weren’t home, the Hip always found a way. I was living in Vancouver when news of Gord’s illness broke, and I was still there months later when the Hip played their last show in Kingston, so my friend and I piled into an at-capacity venue near Gastown to watch the CBC’s live-stream of the show. Without a Hip T-shirt to wear, I grabbed a permanent marker and scrawled THE HIP across my left and right knuckles, desperate to show my support from the west coast. By night’s end, I was dripping tears on those markered-on knuckles, by then already smeared with sweat and beer. I was soon arm-in-arm with a fellow Kingstonian I’d never met before, who wept on my shoulder. I wasn’t home, but I felt like I was.

When I heard of Downie’s passing on Wednesday morning, I was in a tent in southern California, and like many Canadians, I wept and I cursed. But kilometres away, through a macabre slate-grey wall of clouds, sunlight was bursting through like spotlights over Joshua Tree in the distance. I got in my car and kept heading north, not to Canada but in its direction, with “Ahead By A Century” playing, and with Kingston in my heart. But of course, they were the same: when I speak of Kingston, I speak of Gord Downie.

MORE ABOUT GORD DOWNIE:

- Powerful Gord Downie memorial fills Kingston’s Springer Market Square with light and lyrics

- Remembering Gord Downie through his lyrics

- Gord Downie memorial: Fans in Kingston belt ‘Ahead by a Century’

- Gord Downie: Watch a special, two-hour tribute

- Tearful Trudeau makes emotional statement about Gord Downie’s death

- Gord Downie remembered: Tributes to the Tragically Hip frontman

- Gord Downie’s most memorable quotes

- Remembering the life and legacy of Gord Downie (1964 – 2017)