The long, dark past behind the National Gallery’s latest acquisition

John Geddes: The painting shows ‘a peaceful, rich life’. In reality, the Nazis murdered the painting’s Jewish owner and the artist was on the Nazi side.

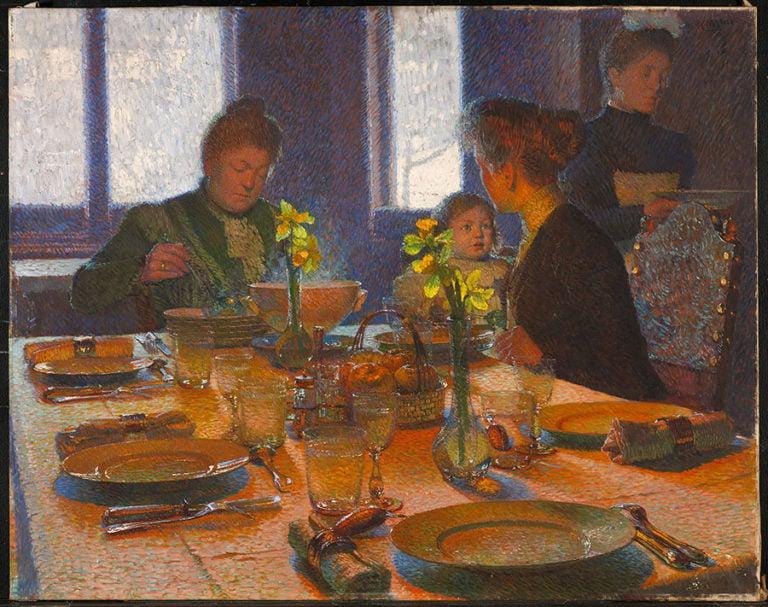

Carl Moll’s “At the Lunch Table”, 1901, oil on canvas, 107 x 136 cm. Purchased 2018 (NGC)

Share

In early 2018, on a winter morning, I visited the National Gallery of Canada especially to see “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer.” It’s one of Gustav Klimt’s celebrated paintings of well-heeled Viennese women from near the beginning of the last century, the most famous of which, in recent years, has been “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I”—the gilded image alluded to in the title of the 2015 movie Woman in Gold, starring Hellen Mirren as the real-life Jewish refugee who fought in court to have the painting, stolen from her family by the Nazis, returned several long decades later.

The gallery in Ottawa, where I live, had made a bit of a splash about securing the long-term loan of a prime Klimt portrait, along with one of his less-familiar forest landscapes, from an unnamed private collector. “Elisabeth Lederer,” which the artist worked on between 1914 and 1916, can’t have disappointed Woman in Gold fans drawn by the publicity. The dewy 20-year-old daughter of his friends and patrons, August and Szerena Lederer, gazes out dreamily at the viewer. Her white dress is diaphanous, her blue cape fancifully decorated. Behind her are arrayed, as if on a sort of textile backdrop, many mysterious Chinese figures, which one critic shrugged off as “cartoonish,” but others analyze for subtle symbolism.

Whether the Asian motif is deep or merely decorative, the overall effect is undeniably lovely. Yet Klimt, I have to admit, has never quite grabbed me. Maybe I suffered too much early exposure to posters of his “Kiss,” the ultimate undergrad decor cliché. Or is it just that I’ve failed to keep up with the times? Klimt’s reputation has soared since 1980, when my intro art history professor suggested we rely on the Penguin Dictionary of Art & Artists for quick reference. Digging out my dogeared copy of the fourth edition from 1976, I found that back then Klimt rated only a brief entry, where he is called “essentially a decorator” who was “perhaps most successful as a designer for the applied arts.”

Even I can see now that he was more than that. Still, on the day I made the acquaintance of his “Elisabeth Lederer,” I found my attention straying. Out of the corner of my eye, I caught a glint of sunlight on glassware, silver and china. So I left Elisabeth to her steady stream of admirers and slipped over to “At the Lunch Table,” which turned out to be a dining-room scene painted in 1901. It depicts the stolid lady of a prosperous Viennese household about to dish out the midday meal. Seated with her at that glimmering table, awaiting their plates, are a pretty toddler and a done-up young woman. A discreet servant hovers behind them.

The label told me this painting was another recent long-term loan from an anonymous private collection, and that the artist was Carl Moll, a name I had not come across before. Naturally I pulled out my iPhone, and quickly learned that Moll and Klimt had been close colleagues. Both were founding members in 1897 of the Vienna Secession, and they quit that seminal art movement together in 1905. Moll’s short Wiki bio also informed me that he liked Van Gogh and pointillism, and then offered this stark detail: “He committed suicide at the end of World War II, in Vienna.”

Standing before “At the Lunch Table”—noticing how the apples in the centrepiece glowed in the sunlight filtering in through the windows behind the frau—I wondered how Moll came to such dismal end 44 years after he executed his calming fin-de-siècle scene. Although he is not a big enough name for the answers to be instantly available, I didn’t have to hunt too hard. According to various sources, Moll was a lifelong anti-Semite. The little girl in the painting was his daughter Maria, who would grow up to marry a Viennese lawyer named Richard Eberstaller and share her husband’s early enthusiasm for Nazism. The three of them—father, daughter, son-in-law—took poison together as the Red Army marched into Vienna on April 12, 1945.

***

Since my first encounter with Moll’s domestic idyl, and with Klimt’s glamorous portrait, I have been troubled, now and then, by how I reacted to them. I failed to sustain interest in a signature work by an admired modernist and gravitated to a genre piece by a relatively obscure bigot. Misgivings about my own taste made me curious about these paintings as artifacts of their moment in history. And that curiosity made me want to know something about, not just the painters, but the individuals in the paintings.

Klimt’s rising celebrity in the early 21st century—as evidenced by the eight- and nine-figure prices his paintings fetch at auction—has helped bring the “golden age” Vienna of the years leading up to World War I closer to the popular imagination. It was the city where Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg composed, where Sigmund Freud and Ludwig Wittgenstein theorized, and where the grand outpouring of creativity was underwritten by art collectors and concert-goers, many of them Jewish, including the Lederers.

About a year after putting “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer” on display, the gallery published an article on its website pulling some of these threads together under the headline, “Tragedy beyond the canvas: Gustav Klimt’s Elisabeth Lederer.” It sketches how the Lederers were among Vienna’s very richest families, and gave Klimt a string of important commissions. He vacationed with them in the countryside. By the time he died in 1918, they owned many of his paintings.

In the 1930s, however, life grew increasingly precarious for Vienna’s Jews, and then, after Hitler annexed Austria in 1938, far beyond precarious. The Nazis wasted no time looting the Lederer collection. Most of the family fled. But Elisabeth stayed put, concocting the story that Klimt, who was not Jewish, was her real father. That bid to half cleanse her blood is believed to have been invented; from exile, her mother, Szerena, trying to protect her daughter, signed an affidavit to verify it. The city’s Nazi regime evidently accepted the ruse, perhaps partly because Klimt had been known for his womanizing. Elisabeth was able to stay on in Vienna, to die there of natural causes in 1944.

By the time of the Anschluss, Klimt had been dead for 20 years. The way his paintings were seen by the Nazis—who were notorious, of course, for cataloguing modern artists as “degenerate”—is rife with contradictions. This surprising story is expertly told by Laura Morowitz, professor of visual arts at New York’s Wagner College, in her 2016 paper, published in Oxford Art Journal, “‘Heil the Hero Klimt!’: Nazi Aesthetics in Vienna and the 1943 Gustav Klimt Retrospective.”

Given the implications of that surprising title, it’s important to keep in mind that Klimt’s close relationships with Jewish patrons and friends—the Lederers foremost among them—were not merely the opportunism of an artist looking for sales. “If Klimt ever had an anti-Semitic thought—hardly unusual for an artist whose career chronology is nearly identical to the Viennese mayoral term of Karl Lueger, the first politician in modern European history to use a populist anti-Semitic platform to ensure his vote—there is no record of it,” Morowitz writes.

This is no small mark of distinction for Klimt. Morowitz frames his career in a Vienna where lofty cultural achievements coexisted with a countervailing undercurrent of anti-Semitism. The young Adolf Hitler was among the aspiring artists drawn there—only to leave a failure, nursing what Morowitz says would prove to be a “life-long grudge.” He visited for the first time in 1906, then again in 1907, when his application to study at the Academy of fine Arts was rejected, and then finally to live in Vienna for several years, starting in the winter of 1908.

That spring Hitler appears not to have attended a major art exhibition, starring Klimt and featuring his student, the noted Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka. Instead of taking in the show, he honed his coruscating disdain for modern art, which Vienna’s reactionaries, according to Morowitz, were already beginning to equate with “Jewish Culture.” After Hitler seized control of Austria in 1938, he sought to extinguish the Viennese cosmopolitanism that had so repelled him in those formative years. Morowitz quotes from the diary of Joseph Goebbels, where the Nazi propaganda minister recorded that Hitler was “determined to break Vienna’s cultural hegemony.”

For any Nazi out to execute that destructive mission, tearing down the legacy of Klimt—trailblazing modernist favoured by Jewish art lovers—might have seemed obvious. But this is where the story Morowitz tells takes an unexpected turn. In 1940 Hitler appointed Baldur von Schirach, the former head of the Hitler Youth and a self-regarding “aesthete and poet,” to rule Vienna. He dutifully deported tens of thousands of Jews to their deaths. When it came to art, though, von Schirach had his own notions. He built a personal collection, largely made up of works expropriated from Jewish families. “Although not shying away from Old Masters,” Morowitz notes, “von Schirach owned works by Vincent van Gogh, Auguste Renoir, and Lovis Corinth—all artists declared ‘degenerate’—and purchased a Gustav Klimt….”

Despite Goebbels’ growing irritation, von Schirach promoted art exhibitions in Vienna that cut against the grain of National Socialist orthodoxy. What was safest for any Nazi to like came down to what Hitler admired. Morowitz says he preferred “above all the works of ancient Rome, but also of the Renaissance.” Among contemporary German artists, that translated into “swollen, brutal classicism.” But, beyond these rough parameters, Nazi arbiters of art were confused. So von Schirach tried to push the boundaries, ultimately by mounting an ambitious Klimt retrospective, including 67 paintings, in 1943. “Nearly a third of the paintings had been expropriated from Jewish families, twelve from the Lederer family alone, all of whose possessions had been seized in 1938,” Morowitz writes.

Von Schirach even commissioned an art historian to write an essay that sought to soften, or even erase, Klimt’s modernist edge, recasting him as steeped in Austrian folk tradition and German philosophical roots. In other words, the sort of painter an SS officer could be proud to loot. “The turbulent, challenging, multi-cultural, and questioning nature of turn-of-the-century Vienna was being refashioned here to fit the Nazi image of the past,” Morowitz says. The effort was not really a success for von Schirach: His standing as a Nazi functionary soon plummeted and he faded from importance. In any case, by the time of his Klimt show, Germany was losing the war on the Eastern Front, and the turn in the fighting that would ultimately bring the Red Army to Vienna had begun.

***

Carl Moll was still alive for those final years of World War II. The placid life he had once idealized was long gone, if it ever existed. In fact, the serenity of “At the Lunch Table” belies internecine family turmoil. Consider the two seated women—leaving aside, for now, the ill-fated toddler, Maria. The middle-aged matron serving soup is Anna Schindler-Bergen, widow of Moll’s teacher, the noted landscape painter Emil Jakob Schindler. When Schindler died in 1892, Carl and Anna had been lovers for some time; they married about three years later. The young woman in the picture is Moll’s stepdaughter Alma, a force of nature who would go on to marry, among other luminaries, the composer and conductor Gustav Mahler.

According to the recent biography Passionate Spirit: The Life of Alma Mahler, by Cate Haste, upper-crust Vienna was utterly smitten with Alma around the time Moll painted “At the Lunch Table.” “At the age of nineteen, with clear skin, and enigmatic smile, lustrous, flowing hair, and piercing, watchful blue eyes,” Haste writes, “Alma was called ‘the most beautiful girl in Vienna’.” Strange, then, that hers is the only face turned away from the viewer in Moll’s composition. Or maybe not so strange: Haste writes that Alma detested Moll. From early childhood, she had reverentially watched her father paint, and scoffed at her stepfather as a second-rate interloper. Haste raises, but cannot answer, the question of how early the precocious Alma might have been onto her mother’s affair with her beloved father’s student and trusted assistant.

In Passionate Spirit’s opening chapters, Alma waltzes across a tableau of turn-of-the-century Vienna that can be transfixing. She comes of age as an aspiring composer in a milieu of overlapping artistic excellence and romantic entanglements. Haste quotes liberally from her diaries—gushy passages about parties, earnest notes on symphony concerts, candid comments about sexual awakening. Alma went on to either marry or conduct affairs with, among others, Mahler, Kokoschka, and the architect Walter Gropius, future founder of the Bauhaus. By the time the Nazis seized Austria, she was married to the noted author Franz Werfel.

What a life. Even Klimt plays a roguish part as Alma’s first overheated infatuation. She’s still a teenager when they share a fervid round of flirtation and ardent letter-writing, along with a couple of memorable kisses, before Moll intervenes, warning Alma of his talented friend’s “brutality.” Never mind—there were other men in Vienna. In 1901, the year of “At the Lunch Table,” Alma caught Mahler’s eye. He was 41, she was 22. “From now on I can live, breathe and exist only if I think of you,” the great composer and conductor wrote to her. They were married in 1902, but he lived only until 1911.

Not everyone in Alma’s circle approved of her choices. When she was earlier toying with marrying a Jewish musician and composer, Alexander Zemlinsky, a disapproving Moll family friend named Max Burckhard advised, “Don’t corrupt good race.” Burckhard didn’t like the match with Mahler either, calling it a “positive sin” and tut-tutting: “A fine girl like you. And such a pedigree too.”

Mahler had to be used to it. Born into a Jewish family of very modest means in 1860, his musical gifts were recognized early. As a young talent, he rose steadily. By 1897, he was in line to be appointed director of the Vienna State Opera, but first had to convert to Catholicism—a necessary step even though Emperor Franz Joseph had publicly declared his trust in “the fidelity and loyalty of the Israelites.” Alma embodied troubling contradictions in the Viennese mindset. In her diary, to pluck just one offhand example, she observed of a friend, “What a pity that [she] is so conspicuously Jewish.” Yet Mahler was no one-off. Alma’s Viennese social circle was predominantly Jewish, as was Werfel, her husband when the Nazis took over.

Together they fled Vienna. During the war years, the émigré couple found their way to Hollywood, where they associated with the likes of Marlene Dietrich, the anti-Nazi screen star, and Erich Maria Remarque, the author of All Quiet on the Western Front. Werfel’s novel The Song of Bernadette was a U.S. bestseller and the movie based on it snagged several Oscars. After 1940, according to Haste, Alma “had almost no contact with Carl Moll or her half sister, Maria, and her husband, Richard Eberstaller, who had all been early Nazi Party supporters.” In far-away America, Alma learned only well after the grim fact that the three of them had killed themselves together in old Vienna, rather than face whatever was coming next as the Russian tanks rolled in. In a final letter, Moll wrote, “I fall asleep unrepentant.”

***

Several months after “At the Lunch Table” caught my eye, the gallery posted an article about the painting on its website under the title, “Tranquility and harmony: Carl Moll’s painting of family life.” It credits Moll for his “great influence on the Secession’s avant-garde program,” lauds him as a “sensitive observer and subtle painter,” and seeks to elevate the painting to something more than a sentimental scene. “The care taken to craft a thoughtful, cheerful lifestyle has a moral dimension,” the article contends, “implying an ordered, peaceful and aesthetically rich life, which was for Moll and many of his contemporaries, the ideal life.”

I’m not sure how much peace and order Moll’s home life actually represented, but that’s the picture he strives to paint. The article, written by a gallery staff member, shifts rather abruptly in its last paragraph to provide this sobering note on the tranquil and harmonious painting’s provenance: “Believed to have been lost for nearly a century, the work was once owned by Siegmund Isaias Zollschan of Vienna, and was among several possessions that he sent to a relative in Canada for safekeeping before the war. Tragically, the Zollschans, a Jewish family, were persecuted by the Nazis and Siegmund perished in the Holocaust. His painting has been cared for by the family in Canada ever since.”

Somewhere between the proposition that Moll imbued his painting with a “moral dimension” and the revelation that the Nazis murdered its Jewish owner, a crucial bit of information has gone missing. It’s that Moll was on the the Nazi side. Debate is possible about whether even such a nasty bit of history should cloud our view of any work of art. However, it’s noteworthy that in the case of “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer,” the gallery came down on the side of choosing, by publishing its “Tragedy beyond the canvass” article, to let the public in on the link between the painting and the Holocaust.

When it comes to Klimt and the Lederers, learning a bit about that history adds depth, with no attendant risk of making any gallery-goer feel queasy about admiring the artist. The same can’t be said about finding out about Moll and his little blended family, and what became of them, especially in light of what befell the owner of his painting.

***

In early June I arranged to interview Anabelle Kienle Ponka, the gallery’s associate curator for European and American Art, about “At the Lunch Table.” We talked over the phone, given coronavirus social-distancing protocols. “I would absolutely say it’s a major painting in his oeuvre,” she said. “It’s very large scale, also highly ambitious. He brings us right into the picture with the familial affection and domesticity.” Her enthusiasm didn’t make raising the matter of Moll’s sordid end any easier. Yet, when I asked if she thought it was the gallery’s responsibility to contend publicly with his full story, Ponka didn’t hesitate. “Oh, it’s absolutely our job to deal with this,” she said, adding that behind-the-scenes deliberations over displaying and ultimately buying the painting were fraught. “We said, ‘Would we acquire an artist who was an active supporter of Hitler’s National Socialist movement?’”

The answer was yes. She said the gallery’s acquisition of “At the Lunch Table” will likely be finalized this fall, meaning it will shift from being on loan to becoming a permanent part of Canada’s national art trove. The Klimt paintings would be, alas, far too expensive for the gallery’s budget. Klimts have sold for staggering sums, including the U.S.$135-million paid for the golden portrait “Adele Bloch-Bauer I” in 2006. The gallery won’t disclose how much it is paying for the Moll painting, but another Moll sold in an online auction in 2013 for around $370,000.

Ponka said Moll’s Nazi sympathies must “factor into our future display.” Asked if ignoring those details in its “Tranquility and Harmony” article was the right decision, Ponka answered flatly, “No, I think that, looking back, we need to face up to that in a different way.”

But simply telling viewers more about Moll’s unsavoury side won’t be enough. As with Klimt’s “Elisabeth Lederer,” the story of the ownership of Moll’s painting adds crucial layers. The gallery’s research shows that Siegmund Zollschan’s niece in Montréal, whose name was Olga Schmerer, kept “At the Lunch Table” until she passed it on as a gift to another relative—who had also fled Nazi persecution as a child—sometime before her death in 1981. It had remained in that family’s hands until the gallery came calling. “They love the painting,” Ponka says, “and it’s given joy.” Hearing that made me feel a shade less uneasy about having liked it at first glance.

So for nearly eight decades the painting remained a hidden, private source of pleasure. Ponka told me the leading Moll experts in Austria had assumed it was lost, and were surprised to learn it had surfaced in Canada. Her excitement about the find is infectious. I asked if she is able to separate her admiration of the art from her feelings about the artist. “No I can’t, I don’t think one can,” she said, adding: “You can hear my German accent; I’m from Stuttgart. I’m quite aware and I’m quite conscious of that part. It was a troubling aspect and we were really grappling with it. We have to get to that extra step. There are uncomfortable truths—there are things in artists that make us like them less.”

***

Dip a toe in Vienna’s golden age and you’re soon swimming in treacherous crosscurrents. I admire the way Morowitz dives right in, unflinchingly addressing the vexing question of how Klimt’s paintings could possibly have appealed to von Schirach, or, for that matter, any Nazi. Among other things, she looks at how Klimt incorporated classical imagery into his designs, and concludes that his “fascination for a chilly, archaic and pagan Greece finds its counterpart in Nazi aesthetics”—that is, in Hitler’s crude distortion of classicism. But identifying this sort of commonality cannot taint Klimt any more than contemplating the Nazis’ fondness for the Ninth Symphony would lead anyone to indict Beethoven.

In her introduction to Passionate Spirit, Haste clearly anticipates objections when she admits to liking her subject, especially the way Alma comes across in those ebullient early diaries. “She is consistently and damningly accused of anti-Semitism,” Haste concedes, “yet she had two Jewish husbands, one of whom she followed into permanent exile to escape the Nazis, several Jewish lovers, and a social circle composed mostly of Jews.” Not everyone interprets the evidence of her life as exculpatory for Alma, though. For instance, in Forbidden Music: The Jewish Composers Banned by the Nazis, Michael Haas describes Mahler’s wife as “an unreformed anti-Semite who seemed to display a near fetish-like preference for Jewish men.”

One way of coping with all this disturbing biography might be, I suppose, to cordon off consideration of lives lived from appreciation of paintings painted. Like Ponka, though, I find clinging to art-for-art’s-sake pieties impossible. I would prefer to have known, when first succumbing to the surface pleasures of “At the Lunch Table,” what lies beneath the illusion. The gallery recently reopened after a prolonged pandemic shutdown; I plan to visit again soon. In room C2015, I’ll take another look at “the most beautiful girl in Vienna,” or at least the back of her neck, under all that pinned-up hair. And then I’ll turn to the other girl—the one who would have to pretend she wasn’t really Jewish in order to remain in her tragic city—hoping that this time I’m able to see what Klimt made of her with more receptive eyes.