A celebration of Robertson Davies (on what would have been his 99th birthday)

Robertson Davies is a permanent fixture in the Canadian canon, yet today, at least among younger readers, he is sadly neglected.

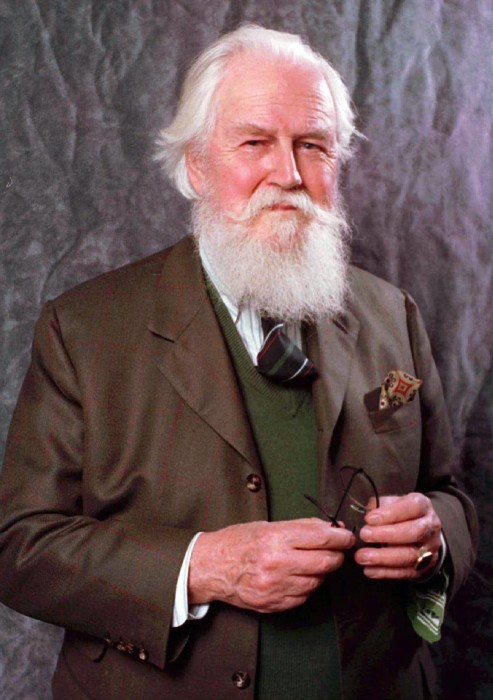

Robertson Davies, seen in a 1992 file photo, widely recognized as one of Canada’s most accomplished authors, died Saturday night Dec. 2, 1995 in a hospital in Orangeville, 50 miles northwest of Toronto, after suffering a stroke, said his secretary Moira Whalon. He was 82. Davies, also a playwright, actor and critic, was mentioned as a possible winner of the 1993 Nobel Prize in literature, which was won by American novelist and essayist Toni Morrison. Davies’ best-known works are two trilogies “Fifth Business” (1970), “The Manticore” (1972) and “World of Wonders” (1975) centered on the fictional Ontario town of Deptford. “The Manticore” won the 1973 Governor General’s award for fiction. (AP Photo/Tom Keller)

Share

Robertson Davies, who would have turned 99 today, is a permanent fixture in the Canadian canon, yet today, at least among younger readers, he is sadly neglected. This is thanks in no small part to the brutal practice now in vogue of judging literature by its political or practical value rather than for its aesthetics. During my teaching practicum in 2008 many teachers said Davies, particularly in Fifth Business, doesn’t speak to today’s multicultural high school student and should no longer be taught. Meanwhile my peers at OISE, Canada’s epicentre of political activism, dismissed the novel–the first installment of the Deptford trilogy– as merely the work of an old white Christian male. In their hands, Davies’ humorous narrative voice and idiosyncratic ideas, such as the notion of history as myth, disappear, and the art is reduced to the author’s racial or gender brand. An insidious threat, these educators and educators-to-be literally judge books by their cover.

Davies is timeless and universal because his wisdom is all encompassing, including, for example, both the worlds of the street hustler and the rare breed of classical academia that transcends boredom and pedantry. Accordingly, the world of his novels is not just original and learned, it’s funny. And so was Davies: While teaching at Massey College in Toronto, the author dared his students to ambush him with water balloons, and to tempt and taunt them he walked around campus on sunny days holding an umbrella! Davies played off the students’ assumption that he, an old-fashioned Caucasian scholar, was a humourless prig.

For Davies, and for canonical authors, wisdom must include humour or else it is fatally incomplete. Perhaps his formidable beard invites people to mistakenly take him too seriously. As Davies states in A Voice From the Attic, “the idea that a wise man must be solemn is bred and preserved among people who have no idea what wisdom is.” Mordecai Richler not only called Davies a “master of magic” but complimented him for looking like a writer, in contrast to most writers who he thought resembled, “drug dealers, card sharpers, barmaids or shoplifters.” Richler wasn’t shy about criticizing Canadian writers, but he repeatedly held up Davies as an outstanding example of a Canadian who, unlike himself, proved himself internationally while remaining in Canada.

And Davies doesn’t write about dull Canadian towns dully. The inhabitants of Deptford fit somewhere between “laughable, lovable simpletons” and those for whom, “incest, sodomy, bestiality, sadism and masochism were supposed to rage behind the lace curtains and in the hayloft while a rigid piety was professed in the streets.” Quite a spectrum. And while the Deptford trilogy isn’t filled with the overt and consciously multicultural cast of the McDonald’s commercial, it’s sufficiently colourful and diverse to include town folk and business tycoons alongside bearded ladies, magicians, and a human frog who can sit on his own head.

It’s curious that while many desperately claim Toronto is a “world-class city,” Davies, who died at the age of 82 in 1992, isn’t a greater source of pride. Like Torontonian Glenn Gould, the author is a first-rate artist appreciated more in Europe, eponymous parks and studios notwithstanding. If we don’t read him, it’s only our loss.