After the apocalypse

Edan Lepucki’s California, though it got a boost from Stephen Colbert, doesn’t leave enough to the imagination

Share

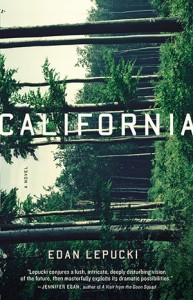

CALIFORNIA

Edan Lepucki

In the not-too-distant future, when soaring oil prices, civil unrest and a series of natural disasters have decimated the population of the United States, a young married couple named Frida and Cal abandon the ruins of Los Angeles and head for the wilderness. They move into an empty shack, living off foraged mushrooms and a few measly crops, until everything changes: Frida realizes she’s pregnant. The couple takes off to the nearest human settlement—one that poses its own dangers, to them and to their child.

This is the premise of the debut from Edan Lepucki, who—despite her own publisher’s modest expectations—looks to have penned a blockbuster. California’s early success comes in large part thanks to Stephen Colbert, who’s used it as a wedge against Amazon. In a feud over ebook pricing, the online retailer discouraged customers from buying titles published by Hachette (both Colbert and Lepucki are Hachette authors). Colbert contends that these tactics hurt first-time novelists like Lepucki the most; he’s repeatedly urged viewers to buy Lepucki’s book at independent stores. But, Amazon vs. Hachette aside, does this novel warrant the attention?

In California, Lepucki has created some memorable characters: Frida, a city girl who thinks longingly back on her days in L.A., spent smoking joints and baking cakes (when the ingredients, now an impossible luxury, were available), and Cal, a perennially useful type. Their relationship is shaped by the man who introduced them, Frida’s brother, Micah. A student-activist-turned-suicide-bomber, Micah blew himself up in a shopping mall, sparking a series of attacks across the U.S. At the opening of the novel, Frida is consumed with pain over his death, whereas Cal wants to leave it behind. But Micah still exerts a strong influence on them both, as Frida’s and Cal’s allegiances—to Micah, and to each other—shift in surprising ways.

Lepucki falls into a common trap of science fiction. She explains too much of the dystopian world she’s creating (character monologues, which give background on how everything fell apart, become particularly grating), and doesn’t leave enough to our imagination. Her writing is suspenseful, although she’s prone to drop the thread too early, delivering a punchline before it’s necessary.

Yet she does bring something fresh to the (increasingly popular) post-apocalyptic genre. With Frida and Cal’s unborn child as a constant and unseen presence, their fear of the future—their need for community, and for each other, at almost any cost—becomes incredibly stark, and that’s what ultimately drives the novel forward.