Margaret Atwood’s urgent new tale of Gilead

In her much-anticipated sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, the renowned author takes her anti-woman dystopia to the age of Trump

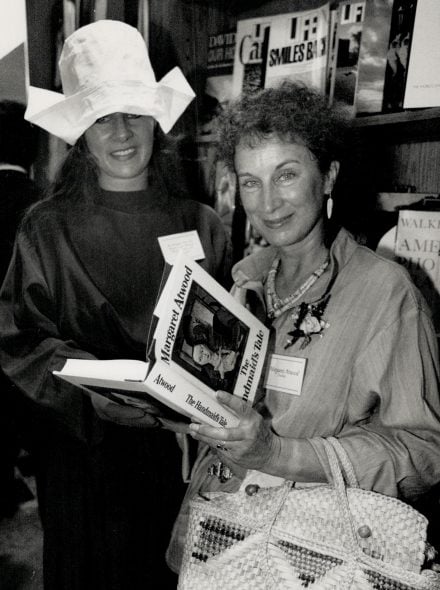

Margaret Atwood in Toronto, Aug 20, 2019. (Photograph by Markian Lozowchuk; Wardrobe courtesy of MGM Television; Wardrobe styling by Jessa Pegg/Judy Inc.; Hair and make-up by GianLuca Orienti/Judy Inc.)

Share

It’s not every literary novel that gets to be launched at a midnight bash at London’s Waterstones Piccadilly, the largest bookshop in Europe. Or every author whose two-hour question-and-answer session at Britain’s National Theatre the next day was to be live-streamed, at up to $20 a ticket, to over 1,000 theatres around the world, including 104 Cineplexes in Canada. But the writer is Margaret Atwood and the novel is The Testaments, the long-awaited sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale. Thirty-four years and eight million copies (in English alone) later, the original novel may be more newsworthy, controversial and popular than ever, thanks to a rancorous American political climate and an acclaimed television series. The sequel—written, Atwood says, only after it became clear in 2016 that “we were going towards the world of The Handmaid’s Tale rather than away from it”—is well on its way along the same path. Weeks before its Sept. 10 release, pre-orders had put The Testaments at No. 3 on Amazon’s top 100 bestsellers list.

The novel, already named to the shortlist for the Man Booker Prize, the Anglosphere’s most prestigious literary award, fully deserves the attention. On the cusp of her 80th birthday this Nov. 18, Atwood has delivered a sequel as creepily gothic, compulsively readable, and richly thematic and topical as its predecessor. Paradoxically—given the depressing fact that the totalitarian theocracy of Gilead is still in place years after the events narrated by handmaid Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale—The Testaments offers more hope, however strange and shadowy that hope is. And more humour, too, most of it Atwood’s unforgiving, needle-to-the-eyeball wit.

In a conversation with Maclean’s, one of only a few prepublication interviews she has agreed to, Atwood discussed topics ranging from her afterlife expectations (both personal and in terms of literary reputation), to the practicalities of keeping her two novels and the Hulu TV Handmaid series in harmony, to why—after 30 years of resistance to the idea—she decided The Testaments was not only doable but should be done. “I’d been thinking about it for a while, though my first thought always was I’d have to be out of my mind to do it,” she confessed. “People had been saying ‘sequel’ for years, and I always said no because I thought what they meant—and what they did mean—was a sequel featuring Offred as the central voice. I could not have done that.” But when history took “a different turn” with Donald Trump, “I reconsidered and thought of a different way of approaching the question. Gilead ends—we know that because we’re told that in the first book—but we’re not told how. So the collapse of totalitarianism takes many forms. Which form could this one take?”

In a conversation with Maclean’s, one of only a few prepublication interviews she has agreed to, Atwood discussed topics ranging from her afterlife expectations (both personal and in terms of literary reputation), to the practicalities of keeping her two novels and the Hulu TV Handmaid series in harmony, to why—after 30 years of resistance to the idea—she decided The Testaments was not only doable but should be done. “I’d been thinking about it for a while, though my first thought always was I’d have to be out of my mind to do it,” she confessed. “People had been saying ‘sequel’ for years, and I always said no because I thought what they meant—and what they did mean—was a sequel featuring Offred as the central voice. I could not have done that.” But when history took “a different turn” with Donald Trump, “I reconsidered and thought of a different way of approaching the question. Gilead ends—we know that because we’re told that in the first book—but we’re not told how. So the collapse of totalitarianism takes many forms. Which form could this one take?”

The novel opens about 16 years after The Handmaid’s Tale—the exact date is left deliberately uncertain—and three new female voices narrate the story. Two of them are young enough not to remember the time before Gilead. One grows up in Canada and the other is a child of the Gilead elite, and the contrast between them is a running commentary on open versus closed, Canada versus the United States. Readers will soon guess who they are, or at least who they are supposed to think the young women are. In a story where almost every female name carries significance and almost every woman has two names, they have three each. More uncertain than their identities, right until the final pages, is the purpose for which their individual reports, known as witness testimonies 369A and 369B, were compiled. Are these accounts of their roles in an anti-Gilead triumph or are they testimony at the treason trial of the third narrator?

And she is Aunt Lydia, the cruelest and most powerful woman in Gilead, head of the brown-robed “aunts” who keep the handmaids in line, who rules her own operatives with “an iron fist in a leather glove in a woolen mitten.” Lydia provides “The Holograph of Ardua Hall,” a secretly written apologia pro vita sua—she hides it in her forbidden copy of Cardinal Newman’s defence of his life—meant for someone, someday, to pick up and judge how she, a former family court justice, got here from there. Mostly, according to Lydia, a masterful and seductive apologist, a survival instinct took her down “the road more travelled,” taking the first step to save herself, and the second to “avoid the consequences of the first,” and so on to the next.

Now she of the infamous “rat’s teeth” of Handmaid has turned her rat cunning to the question of her eventual demise. She has survived the violent coming of Gilead and three purges since then, but she’s in her 70s now. Death is close enough, possibly from natural causes but more likely, in Lydia’s cold-eyed assessment, from running out of luck in a fourth purge. Aunt Lydia decides to act while she still has some say in how she goes out: “Oh, and on who to take down with me. I have made my list.” With bloody-minded precision, she sets in motion a costly plot—the high price paid not just by her but by innocent bystanders—to destroy Gilead.

As good as The Testaments is as a stand-alone novel, it is a measure of Atwood’s achievement that her new book forms a brilliant diptych with The Handmaid’s Tale. Each explains and expands the other. To re-read the original in the light of the sequel is to add yet another layer of context to the single most famous novel in Atwood’s prolific career. The Handmaid’s Tale grew out of a tangled skein of roots. There was Atwood’s robust feminism, her already-deep ecological concerns and her abiding interest in her Puritan New England ancestors, including Mary Webster, who somehow survived being hanged as a witch in 1685. (The Handmaid’s Tale is dedicated to “Half-Hanged Mary,” the subject of Atwood’s 1995 poem of the same name, and Perry Miller, a historian of Puritanism who was among Atwood’s mentors during her time at Harvard.) But the main factor in Handmaid’s genesis was the political situation of the early 1980s: Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, Ronald Reagan’s America, the medieval theocracy in Iran, the horrific state kidnapping of children that marked the Argentinian “Dirty War” and the enforced childbearing of Romania, all of which to varying degrees raised alarm among those dedicated to women’s rights, especially reproductive rights. The idea for The Handmaid’s Tale arose when she was having dinner with a friend in 1981. Talk turned to “some of the more absolutist pronouncements of right-wing religious fundamentalism,” Atwood later wrote, and someone said, “No one thinks about what it would be like to actually act it out.” The book then “came into my head.”

The result in 1985 was a still-vibrant dystopian satire set in the near future—more or less now, that is—when environmental degradation has cratered human fertility and violent Christian reactionaries known as the Sons of Jacob have overthrown the U.S. government. In the new totalitarian Republic of Gilead, anchored in a New England that has returned to its Puritan roots, women are valued only as breeders. Even the relatively privileged—the wives of the elite and the aunts—are virtual slaves, forbidden to own property or, aside from the aunts, even to read or write. The title character and narrator is so completely the possession of Fred, the Gilead commander who needs her womb to acquire an heir for his childless marriage, that her own name is erased, though it is likely June. She is known as Offred, after her owner, a very Atwoodian pun on “offered,” and like the other handmaids she dresses in the now iconic Dutch milkmaid-inspired red robe and white bonnet that clothe Elisabeth Moss on TV.

The storyline—an unflinching, suspenseful exploration of misogyny in action—is captivating enough to obscure some of the novel’s underlying themes. They include frequent musings from Offred on how “we lived in the time before,” ignoring the clear indications something like Gilead was coming, and the role women play in their own oppression: both overtly, as in the case of the aunts, and by undermining one another. (“Handmaid’s Tale, Cat’s Eye and The Robber Bride demolish the notion that women have an innate, God-given moral superiority,” Atwood once told an academic roundtable in France.) And the chillingly opaque ending of Offred’s story, when she literally steps into the unknown— a van driven either by the Mayday resistance movement or by Gilead agents—tends to be thought of as the book’s ending.

But it’s not. The “Historical Notes” that follow Offred’s leap into the dark—the proceedings of an academic conference held in 2195—illustrate what is Atwood’s single most consistent theme throughout her writing: Who gets to tell the story and who has the power to suppress it? The relatively far-future setting of the conference makes it clear that Gilead has fallen some time ago—there is progress in human affairs—but its seeds remain, however dormant. Male voices still shape, and distort, female stories.

The Handmaid’s Tale was a spectacular success on its release, nominated for numerous awards, winning the Governor General’s Literary Award and—despite Atwood’s vociferous objection that she did not write (down-market) sci-fi—winning the Arthur C. Clarke Award, the U.K.’s most prestigious science fiction prize. The novel became an instant feminist classic. Although it has never been out of print, it carried that classic, as opposed to urgent, status into the 1990s. Gina Wisker, a contemporary literature professor at the University of Brighton in Britain, says that when she began teaching The Handmaid’s Tale a quarter-century ago, it was during a time of complacency for her female students. They admired Atwood’s dystopian work but believed “we didn’t have to speak about feminist writing any more, that those battles for women’s rights were won long ago.”

Atwood, though, never held that opinion. Less a tale about a past possibility, now dead and buried, she says now, Handmaid was more an exploration of what turned out to be “a bullet dodged,” fired by a gun that was cocked and loaded again in the 21st century. “In the two elections Obama won, The Handmaid’s Tale was a frequent meme because of the things that the Republicans were saying,” Atwood observes. “What those people would have done then had they taken power was pretty clear, just as it was clear in the 1980s what their desired goals were.”

Then Donald Trump came down his golden escalator on June 16, 2015, to talk about Mexican rapists. The following April, the Hulu series was announced. Trump was elected president in November 2016, despite his retrograde view of women and associated behaviours, with all that promised in terms of the potential appointment of Supreme Court justices hostile to the legal precedent that allowed abortion access in the United States and of the emboldening of state-level anti-abortion forces. In January 2017, Trump’s inauguration was followed the next day in Washington by the 200,000-strong Women’s March, and in April of that year—the same year the #MeToo movement took flight—the first Handmaid’s Tale TV episode was broadcast. In the midst of this matrix of events, across the border in Toronto, Margaret Atwood was changing her mind.

Soon women around America, and as far afield as Ireland and Argentina, began attending protests dressed as Offred, essentially eclipsing, at least in terms of visibility, the pink hats worn as identity badges at the Women’s March. The novel itself was increasingly present in internet chatter and on bestseller lists. In February, after the inauguration and march but before the TV show aired, Atwood wrote her various editors—including Canadians Louise Dennys and Martha Kanya-Forstner—about what she had been doing since around election day: plotting out a sequel after all.

Small wonder, then, that The Testaments is now receiving Harry Potter-level treatment, or as close to it as any novel for adults could expect. That meant a ferocious non-disclosure agreement for early readers set to last until Sept. 6, four days before publication, and an equally strong temptation to break it (the embargo was shattered Sept. 3). Still, Atwood was to wait until 11 p.m. London time on Sept. 9 before reading from her opening chapter in Waterstones. Indie bookstores are holding themed events and encouraging handmaid wear. A few shops are staying open until midnight Sept. 9, while others—cognizant their clients are working women—are letting their customers in early the next day and providing breakfast. For many indies, the arrival of The Testaments is a political as well as a literary moment: in Duluth, Minn., Zenith Bookstore is sending a portion of its pre-order profits to a centre for sexual assault victims.

Part of the pre-release buzz speculated on what Atwood might do to reconcile TV screen and printed page. As was notoriously the case with the HBO version of George R.R. Martin’s multivolume, but incomplete, Game of Thrones saga, the Hulu series eventually ran out of author-provided source material. Season 1 covered the entirety of Atwood’s Handmaid novel, leaving show writer Bruce Miller to strike out on his own for Seasons 2 and 3 (with a fourth on the way). The show is more militantly resistant and visibly violent than the book, just as Moss’s June/Offred is far more combative than the Scheherazade-like but decidedly unheroic storyteller of the novel. (Atwood once described her Offred as “an ordinary, more or less cowardly woman.”) But the issue was far less acute than it was with GOT, where future episodes and future novels had to cover the same ground. The TV Handmaid carries on in the days immediately following the last scene in the novel, while The Testaments starts 16 years later, territory that Miller is unlikely to face. But the two genres still had to coalesce in the backstory when Aunt Lydia’s past began to emerge this July during Season 3.

There is a regular exchange of information with Miller, Atwood says. “I read all the scripts, though I have no actual power—I just get to say things like, ‘What are you thinking?’ And I don’t have to say that really often. We discuss what the culture of Gilead would be like, what certain characters’ motivations might be, and, of course, we had to negotiate a bit on Lydia so things would line up.” Actually, divide up: Lydia, it turns out, had two careers in the “time before,” working briefly as a teacher before becoming a judge. The former looks set to be a gold mine of motivation for Miller, while The Testaments glosses over school days to reach back to Lydia’s abusive childhood and then ahead into her legal chambers as Gilead thugs burst in after the coup. The novel’s main backstory focus, in fact, is on a male commander’s shrewd read of Lydia’s capacity and character, their mutual recognition that her “lethal combination of law degree and uterus” allowed her no room to manoeuvre and the vicious abuse he inflicts to convince Lydia to make common cause with the regime.

“There are various opinions about Aunt Lydia,” Atwood says evenly of her main character. That’s not strictly true among fans right now, unless the division is over whether Lydia should be shot or hanged. But The Testaments will bring some readers to share Atwood’s ironic regard for her evil witch (half-hanged Lydia?). More will probably view her, as evangelicals claim to regard Trump, as a repulsive but invaluable ally. Lydia’s desire to not go into that good night alone “is me channeling Marilyn French,” laughs Atwood. After the celebrated American feminist writer was diagnosed with esophageal cancer in the early 1990s, “she announced she would like to take somebody down with her, and I said ‘Marilyn, who would you like to take down with you?’ and she said, ‘Newt Gingrich.’” (Then the Republican Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Gingrich is now a prominent Trump cheerleader.)

French is not the only eminent female writer channelled by The Testaments’ main narrator. Lydia channels Atwood just as reliably, sharing her creator’s career-long interest in who gets to control voices, who gets their story out. Atwood too is speaking when Lydia forces herself to pause before committing irrevocably to her scheme. Should she stick to the safe path, meaning to maintain silence, or put her thoughts out into the world? If so, “future reader,” she writes, “I would destroy you along with these pages. What a godlike feeling! I waver, I waver.” No one writes anything “without postulating a reader,” Atwood says of Lydia’s uncertainty, “and sometimes you think of extinguishing that reader. But then you don’t.”

There’s more reason than an approaching milestone birthday, then, to ask questions of Atwood about legacy, reputation and retirement, even when an interviewer can guess the probable answers. With regard to retiring, writers don’t, period, and if it’s said they do, that’s “code for cancer” or some other disability, Atwood responds. If you’re born to write, let alone someone who believes “fiction writing is the guardian of the moral and ethical sense of the community”—and she is both—then a retirement for the sake of, say, more birdwatching will end repeatedly. It would be “one farewell tour after another,” to the annoyance of all: “How many ‘It’s time for your close-up, Ms. Desmond’ moments can we have?”

As for legacy and posthumous reputation, Margaret Atwood officially does not care. She has always practised a prickly kind of deflection when asked such questions, having received a lot of attention in what she believes—quite naturally, since she, too, loves the slaughter of sacred cows—to be a country whose unofficial motto is an Alice Munro title, Who Do You Think You Are?

Honours and positive attention, amounting almost to adulation at times, have followed Atwood throughout her writing life to an unprecedented extent. It’s almost inconceivable that the winner of the 1966 Governor General’s Poetry Award has been nominated for the Booker Prize 53 years later. But her career has also been accompanied by a constant stream of barbs, snark and criticism, proportionally more of it, to the surprise of more than one foreign admirer, from her compatriots. The life of a successful Canadian writer—indeed, the proof of the success—she once told American author Joyce Carol Oates, is “fervent attack and rejection.” The GG prize, awarded for poems she published at age 25, prompted a Maclean’s editor to suggest a profile that was later cancelled, Atwood says, by a senior editor who said, “no woman under 30 has anything to say worth listening to.” (Instead, Margaret Eleanor Atwood first appeared in this magazine on the occasion of the moon landing a half century ago, contributing a poem with the carefully gender-neutral signature of M.E. Atwood.)

Atwood has always guarded herself against the criticism, which comes from all sides, for being a mere “women’s” writer or an uppity feminist, a strident nationalist or too much an “American” author, or even for her avid embrace of technology and social media. (Her current crime is simply being too much present: “Our Mother of the Written Word,” wrote author and cultural commentator Stephen Marche in 2015, is “sometimes the smothering mother . . . sometimes the lecturing mother.”) But Atwood’s wall has also protected her from the weight of the adulation, which has long included admirers’ not unreasonable hopes of a Nobel Prize in Literature for her. That’s a more remote possibility than it may once have been, given that her countrywoman Alice Munro won the award as recently as 2013.

The author acted early to carve out space and privacy while protecting her brand. In the mid-1960s Atwood was one of the first writers in what was scarcely more than a cottage industry in Canada to realize the importance of agents. In 1976, she was the first Canadian to incorporate her business as a writer, founding O.W. Toad, an anagram of her name. And it’s notable, about the private Atwood, that the earliest relationships between her and the key figures in her career—all of them, from agent to editors, women—became long-lasting and loyal friendships. Her wide Twitter following, almost two million strong, often displays as much generosity of spirit. In 2018 she gave a stuck Ontario student some help with a Handmaid’s Tale essay, while stressing once again one of the novel’s frequently glossed-over themes: “It’s not just women who are controlled in the book. It’s everyone except those at the top. Gilead is a theocratic totalitarianism, not simply a men-have-power women-do-not world.”

None of the protective measures would have been necessary had it not been for the work, as extraordinary in its quantity as its quality. There are 24 books of poetry—a case can be made that, in the end, Atwood will be honoured most for her poetry—as well as eight children’s books and eight books of short fiction. There are 10 non-fiction titles, primarily literary and social criticism, some of them—notably Survival, Negotiating With the Dead and Payback—almost as well-known as her fiction. And then there are the novels, 17 in number now over a half century: The Edible Woman, Surfacing, Lady Oracle, Life Before Man, Bodily Harm, The Handmaid’s Tale, Cat’s Eye, The Robber Bride, Alias Grace, The Blind Assassin, Oryx and Crake, The Penelopiad, The Year of the Flood, MaddAddam, The Heart Goes Last, Hag-Seed, The Testaments. And, in recognition for her work, a host of literary prize nominations and awards, including the GG (twice), the Booker and the Scotiabank Giller. Atwood’s thoughts on her native land, on the lives of women and respect for the natural world have been persistent themes.

Many of the novels speak intimately to readers, especially women, particularly in the way female characters are always aware—whether they fight them or accept them—of social expectations borne by women. The lead epigraph to The Testaments—and Atwood’s epigraphs are all carefully chosen—comes from (female) Victorian novelist George Eliot: “Every woman is supposed to have the same set of motives, or else to be a monster.” For similar reasons, editor Louise Dennys talks of how much Cat’s Eye meant to her as an immigrant woman in Canada, while British academic Gina Wisker comments on how Atwood has “dominated my professional life since it began. She has such a clear head on women’s lives, plus the environmental concerns; the wry, concentrated writing, all of it so well crafted, such good stories. Toni Morrison was the only other giant of her time as eloquent and as focused on human rights.”

Biographer Nathalie Cooke notes how Atwood, more than any other writer, pulled Canada’s history and geography onto the international literary stage, moving from her own initial hesitation in making her Canadian setting explicit in The Edible Woman (1969) to taking it for granted with Alias Grace (1996). “The quality of her work and her fame leads her foreign readers to compare her with other international first-rankers. Her nationality is irrelevant there, but still apparent in ironic inside Canadian jokes and self-deprecation.” For Cooke, though, as for most critics and admirers, Atwood’s greatest gift lies in her career-long prescience: she wrote about feminist issues just when society was beginning to tackle them; she used massive environmental degradation as the underpinning of Gilead before climate change was on the radar; she published Alias Grace, a story about a servant accused of murder in pre-Confederation Ontario that explored ambivalent views about female criminals, when Canada was grappling with what to think of Karla Homolka. “Atwood is always just ahead of what the culture is thinking,” Vancouver writer Brian Brett once said. “Always had that grace. Could sense what was going to be a ‘paradigm crisis.’”

Atwood’s effective, often witty, self-protection gave her a reputation early on for being “frightening” to press on anything. She was asked about that tag in a 1976 Maclean’s interview, which began by listing all the varied images Canadians held of her: “goddess, bitch, nationalist, feminist, Venus, madwoman and earth mother.” She was probably as frightening as anyone backed against a wall, Atwood replied to interviewer Helen Slinger. “[But] I think it’s probably harder to get me into that situation, because I’m always looking behind, over my shoulder; I know where the wall is. You’ll notice it is you who’s sitting in the corner.”

In her 2019 Maclean’s interview, though, Atwood’s deflections on the subject of her afterlife move seamlessly between an awareness of the patterns of literary history and whimsicality. “For a long time in the 20th century the Victorian writers were considered vulgar. Who you were supposed to be interested in was John Donne. But the Victorians came roaring back—you remember the era of Pre-Raphaelite calendars and postcards? And this too shall pass. We’re no longer that keen on flower fairies. A writers’ generation that feels dominated by the generation before it tries to get rid of them. And they do, until the repressed return. So everybody will denounce me after I die and they’ll do that for about 10 years. Overrated they will say. Well, I don’t care what happens to me after I’m dead, except in terms of my corpse disposal.”

Sorry?

“Corpse disposal. There are new greener and more space-saving alternatives now for that. For a while the thing to do was to get yourself incinerated, but that’s very energy consumptive.” Can’t she be buried in a forest? “That’s one choice, vividly embraced by God’s Gardeners [the devout ecologists of Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy]. That’s what they were doing. But now there are ways of getting yourself composted and sprinkled about on the rosebushes.” Atwood, who as a child loved digging in the backyard in hopes of finding interesting items, feels bad about not leaving “something for future archeologists to dig up.” She’s been considering, she says, “an item cache that would do as well [as a body], grave goods without the corpse. I think that would be good.” What would she put in it? “Maybe a toaster oven, for a ‘What is this?’ moment for the finders. ‘They worshipped it like a god!’ A little home grill, perhaps. I’m quite keen on them.”

READ MORE: For black women, The Handmaid’s Tale’s dystopia is real—and telling

At any rate, she wouldn’t be around to care about her reputation, Atwood concludes. She pauses to adjust that conclusion. No, not physically around, but perhaps someone could come to wherever she’s taken up residence as a ghost to let her know how things are going. “What do you think I should haunt,” asks the quintessential Toronto writer. “Casa Loma?” Maybe the Ontario legislature, is the reply, Queen’s Park being just as Gothic a pile and probably fuller of haunt-worthy people. “Yes!” she laughs before adding, in her best quavering scary-movie voice, “I’m coming to get you, for what you did to the libraries.” (Please note, Premier Ford.)

Given that Atwood won’t talk about it, The Testaments itself has to speak for its place in the long arc of her career. The environment and women’s rights are there, obviously, although the latter plays out as much under the story’s surface as on it. In Gilead, all women’s names, from the aunts (named after household products) to the young girls, are signifiers. Witness A reveals how she was known while growing up among the Gilead elite—as Agnes Jemima—scant pages after Lydia’s Eastertide musings about “lambs being slaughtered.” In Christian theology, Jesus Christ, who dies to save mankind, is the “lamb of God,” the Agnus Dei, while Agnes is a daughter in Job’s second family, the one God granted him after God destroyed Job’s first, making A simultaneously sacrifice and restitution for sacrifice. Then there’s Shunammite, a schoolyard frenemy of Agnes, whose name comes from the Biblical term for the inhabitants of Shunem village, the most famous of whom was Abishag, the beautiful 12-year-old brought to warm the bed of the elderly King David. It’s inevitable that Shunammite will become the fifth wife of an especially repulsive commander, who has murdered his previous four child brides as they have aged out.

The focus on child brides and other sexual abuse of girls signals the most significant shift in emphasis from the original book, dominated by the oppression of the handmaids, to The Testaments’ exploration of other sexual crimes in an older and more established Gilead. Exploitation of the handmaids goes on, naturally, but now the regime’s elite men have a generation of their own female children to cruelly abuse—whether those girls are literally their own or were taken from their mothers before the women were killed, in the manner of the Argentinian junta of the Dirty War.

It’s a reflection, too, of the concerns and focus of the #MeToo era. More than once in Handmaid, Offred speaks to the shade of her mother, a militant early feminist who took part in pornography burnings and Take Back the Night marches in the 1970s. Offred’s (and Atwood’s) aim is to ironically ask her mother, “You wanted to carve out a women’s world. How do you like this one? It is, after all, a bit safer out on the streets.” But Offred’s memory of feminist issues also speaks to the earlier era’s emphasis on outsiders’ sexual violence against women, while #MeToo’s emphasis has been on intimate sexual assault, abusive acts committed with impunity by men known to their victims. “Some cultures,” Atwood comments dryly, “wouldn’t call it domestic abuse; they’d call it the way things are.”

The sequel also has more Canadian content than the original. Some of the sequel takes place in this country and includes the ongoing, frequently comic, contrast between the younger narrators, witnesses Canadian B and (sort of) American A. Atwood’s tone on her native land is best captured by comments from two foreigners. A Texan Mayday operative calls Canada’s attitude and actions toward Gilead “sloppy in a good way.” But more telling of Atwood’s ironically affectionate and approving attitude appears when Agnes says that her adoptive mother, Tabitha (a good witch), was—despite having literally stolen Agnes from her birth mother—someone who strove “to be as good a person as was possible, under the circumstances.”

“Unless you want to throw yourself in front of the bulldozer and get squashed flat,” says Atwood, that classic Canadian qualifier has to rule. “One has to avoid representing Canada as an ideal place in and of itself. Canada has always been that place where you believe you can run away to and be safe or at least safer than in the place you ran away from. And also the place that has to walk a fine line with the place to the south. Guess who’s got the bigger army?” So Canada obfuscates and caves in when necessary—“Cavemen, the Canadians,” says one angry Mayday member; “Sneeze and they fall over”—and mires itself deliberately in bureaucratic delay. “Mayday is not officially tolerated in Canada, but is unofficially,” laughs Atwood. “It’s like terrorist outfits in the Middle East that are harboured but not officially allowed, with Canada always assuring Gilead, ‘Oh yeah, we’re trying to weed them out, we’re trying really hard.’”

The Testaments is a novel from a writer still at the height of her powers, and “fresh evidence,” according to Louise Dennys, of “the prophetic sense that [Atwood] shares with many great writers, the way she has her finger on the pulse of us all, and her unequalled ability to work with these many layers. Together, The Handmaid’s Tale and its sequel are right up there with Nineteen Eighty-four and Brave New World.” For Atwood, Dennys adds, “there’s no end in sight, 80th birthday notwithstanding. She’s a touchstone for our times.”

This article appears in print in the October 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Atwood’s urgent new tale of Gilead.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.

Top portrait by Markian Lozowchuk