Margaret Atwood on the stark differences ‘back home’ before and after the Great War

Although nothing was shelled or destroyed, everything changed on the home front

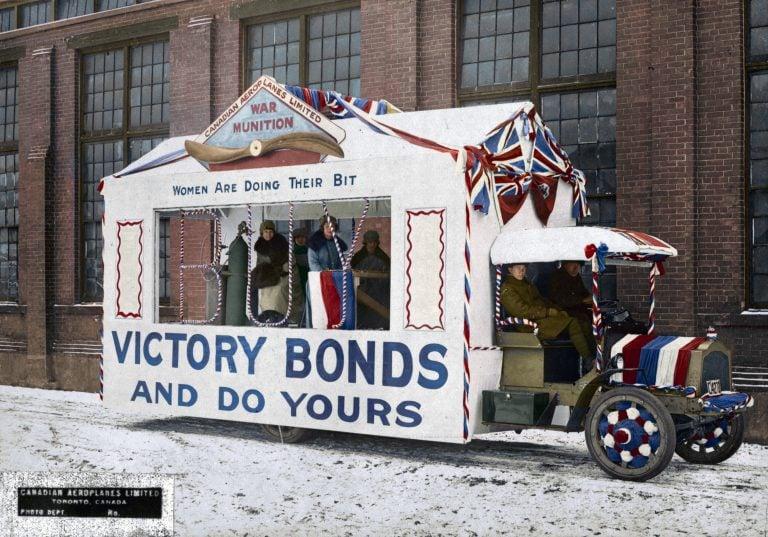

This photo of a Canadian Aeroplane Victory Loan Float c. 1917 is one of the images in the Vimy Foundation’s ‘They Fought in Colour,’ a new book that collects 260 digitally colourized photographs showcasing Canada’s contribution to the First World War. (John Boyd, PA-025181/Library and Archives Canada/Vimy Foundation)

Share

You can’t be my age in Canada and have escaped the impact of the Great War. I was born in 1939—only 20-odd years after that war ended—which means I am old enough to have known people who were actually in that war. Almost every Canadian family then had a relative—an uncle, a grandfather, an older cousin of some kind—who had fought in it and who might even have been killed or wounded in it. One of my boyfriends had a father who’d worked with the “war horses,” still used then to haul heavy equipment. I didn’t talk to him about it much at the time; now I wish I had.

In the 1940s and early 1950s—when I was in public school and then in high school—Remembrance Day was a solemn occasion. We all wore poppies and memorized In Flanders Fields. We listened to the wreath-laying ceremonies on the radio—they were broadcast over the school PA system, once this technology appeared. We heard the cannon salute, the recitations, the sounding of the trumpet: first, the “Last Post,” the call to sleep, which signified death; and then, at the end, “Reveille,” the call to awaken, which signified the Resurrection. We heard the lines from Laurence Binyon’s poem For the Fallen, with its pledge to remember.

RELATED: Surreal colour photos show Canada’s contribution to the Great War

But remember what? The Second World War, definitely—we’d spent our earlier childhoods in that wartime—but the First World War? What had happened, exactly? And why? Nobody told us, exactly. My own take on it was vague, apart from the larks still bravely singing, scarce heard amid the guns below. It was a terrible thing; that much was clear. Whatever its causes, it marked the end of an era, the era of the once-dominant British Empire; though, when we were singing Rule, Britannia! in our late-1940s classrooms, we didn’t know that yet.

In 1997 or so I set out to write a novel set in 20th-century Canada. It was to begin just before the Great War, in that Edwardian age that, looking back, seems to have been so hopeful, so golden. There was a “before the war,” there was an “after the war,” and the two worlds were very different. I wanted to try to grasp those changes: in my novel, the Great War would shatter lives and families, as it did in real life; its baneful effects would persist for long afterwards, as they did in real life. My novel was not to be a war novel as such—no trenches, no gas attacks—but rather a story about the lived impacts of that war on those “back home.”

This book was to be based on the memories of my mother, and also those of my grandmother, transmitted through my mother and my aunts—my extended family went in for a lot of oral history, not that they used this term—but all of these people were too nice to feature in any novel by me. However, throughout my childhood, their stories had provided me with many anecdotes.

“In the Halifax explosion, Uncle Fred was blown right out of the second-storey window and landed on the street. He was still in his bed.”

“But Aunt Rose fell down through two floors, into the cellar.”

“She lost the baby, though.”

“They were lucky! Thousands were killed.”

What did ordinary people do in the war if they weren’t anywhere near the battlefields? They wrote letters to loved ones overseas and waited anxiously for answers. They dreaded bad news: Who had been killed in action? How many? Sometimes towns would lose all of their young men in a single day: the catastrophe would be in the papers even before the official telegrams began to arrive.

RELATED: What kept Canadian soldiers committed during the First World War?

Many people had war-connected jobs. Women stepped into jobs that would have been done by men if there had been enough men remaining to do them. Women ran farms, worked in factories making shells and other military equipment, and sewed uniforms and war gear, including the trench coats that became such an important garment for those living in the cold wet mud-tunnels of the front.

Women also tended gardens, ran canning clubs to preserve food, sold Victory Bonds and helped with recruitment drives. They joined war committees, raising money to send care packages to the troops, or to train nurses to serve not only overseas but—increasingly—back home, tending the soldiers who were too mangled to be patched up and sent back to the trenches.

My grandmother was a member of a ladies’ knitting circle: its members knitted washcloths, then graduated to scarves, and if they were very good knitters, they could proceed to balaclavas and socks. (My grandmother, being a fine bridge player but a terrible knitter, never made it past washcloths.)

It was from her that the phrase “Remember the starving Armenians” made it into the family vocabulary, to be used for decades on children such as myself who didn’t want to eat their bread crusts or their cooked carrots. I later learned that it was a widespread saying in the First World War: news of the slaughter and starvation of Armenians at the hands of the Ottoman Empire had made it to Canada. Some Armenian orphans were even rescued and shipped across the Atlantic, and settled in Canada. My high school year contained several of their descendants; one was my friend. She was a smiling, happy girl, or so she appeared, but it became clear to me, years later, that the suffering caused by this catastrophe was not confined to one generation.

My grandfather was a country doctor in the Annapolis Valley of Nova Scotia. He had been an officer in the Medical Corps for the Nova Scotia militia’s fall training camps, but when the war broke out, he joined the regular army and was promoted to captain. During the war, he did two jobs: his Medical Corps job at Camp Aldershot, and, in his off hours, his private medical practice. He was sent to Halifax on the first relief train to treat the victims of the Halifax explosion, but his own closest brush with death was during the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918-19. This flu was said to be particularly lethal because of the weakness of the many war-wounded. The doctor’s whole family got the flu—five children and both parents—all at the same time.

“Who took care of you?” I asked my mother.

“I suppose it was Father.”

“Even though he was sick, too?”

“Well, somebody must have because none of us died.”

On Nov. 11, 1918, after four punishing years, the Great War was suddenly over. Although nothing in Canada had been shelled or destroyed, everything had changed. Newspapers greeted the news with headlines in huge type: “GREAT WAR ENDS.” My mother was born in 1909, so she was old enough to remember what the end of the war felt like. The church bells began to ring all over Canada, even in my mother’s small Nova Scotia village. To the end of her life, this ringing of bells—so strange for a weekday—remained one of her clearest memories.

The bell-ringing made it into my novel, as did the ladies’ knitting circle. So did a family blighted by death and war trauma, and a mangled soldier. And so did the puzzle of commemoration: How to explain and portray such a devastating event? It’s a conversation we are still having.

Excerpted from They Fought in Colour / La Guerre en couleur by the Vimy Foundation © 2018 by the Vimy Foundation. All rights reserved. Published by Dundurn Press.