Mary Lawson: Why I write about the Canadian Shield

The Canadian novelist on her profound, unreasoning love of the landscape: ‘The the way the mist lifted slowly off the lake in the early morning, the smoothness of water sliding over your skin, the clear looping call of the whippoorwill’

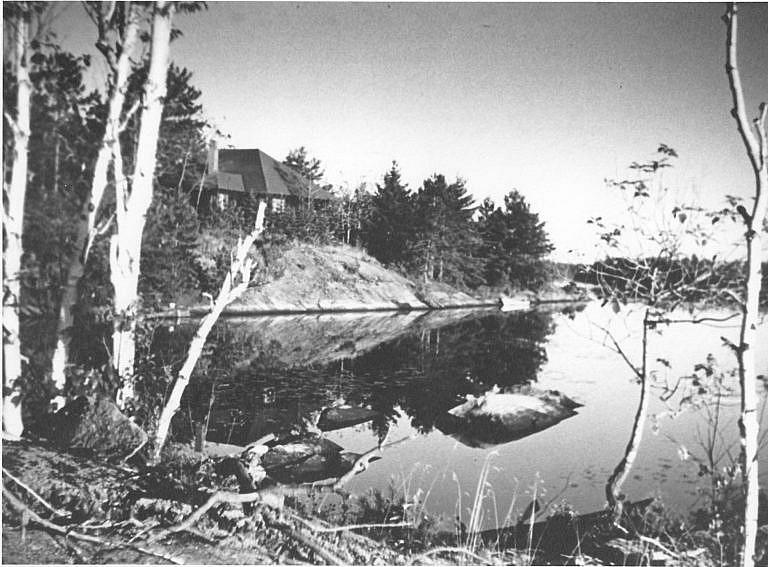

Mary Lawson’s family cottage ca. 1920 (Courtesy of Mary Lawson)

Share

After almost a decade, Mary Lawson releases a new novel, A Town Called Solace, on Feb. 16. Her 2002 debut, Crow Lake, was a New York Times bestseller and a Book of the Year, while her second, The Other Side of the Bridge, was longlisted for the Booker. All of her novels are set in the Canadian Shield territory of Northern Ontario.

“I know every tree, every rock, every boggy bit of marshland so well, that even though I almost always arrive after dark I can feel them around me, lying there in the darkness as if they were my own bones.”

Crow Lake

At one end of the portage, a few yards from the lake, was a granite outcrop about 30 feet high, curving around a small clearing. The rockface had been chiselled by time (lots of it, three billion years, give or take) and ice (more recent, but lots of that too, several kilometres deep in places) into rough tiers so that it formed a small, intimate, though not wonderfully comfortable amphitheatre, fringed around the edges by red and white pines.

God knows how long the portage itself had been in existence, winding its way across the long smooth slabs of rock, skirting small pines and birches, clumps of sumac, blueberry bushes. It may have been made by the Anishinaabe, long before we Europeans arrived. Certainly by the time I’m talking about—a hot sunny Sunday in the summer of 1928—the trail looked as if it had been there since the day the earth was born.

In one corner of the amphitheatre (if amphitheatres can be said to have corners) stood a rough pulpit made of birch. Despite the fact that apart from its beauty, the principal allure of Ontario’s Muskoka area back then was that it was a long way from other people, the few scattered families who had cottages on the lake had found they wanted to see each other from time to time. Where better than at church? It didn’t matter what denomination, all were welcome; the preacher could vary according to who was there to preach. No need for a building, this was perfect as it stood: celestially beautiful, the right shape for small communal gatherings, plenty of rocks to sit on, and because the portage linked the two main arms of the lake, accessible to pretty much everyone. And pretty much everyone came.

The elderly brought cushions. If it was raining or looked as if it might, they brought umbrellas.

On a rock on the top tier, without a cushion, sat my mother, age 17. She wasn’t sitting as a young lady should, back straight, knees together; she was slouching, elbows on knees. There is a possibility that from the lower tiers you could see up her skirt. (I’m guessing all of this—I wasn’t even dreamed of yet—but I’m confident that it was so: I’ve never known anyone as unconscious of or indifferent to her appearance as my mother. It wasn’t that she hadn’t been taught the social niceties, she’d been very properly brought up; it was just that she didn’t notice and didn’t care. She was the despair of her mother.)

She had chosen the top tier in order to have a good view of the portage. People were starting to arrive. Half a dozen canoes and rowboats were being tied to convenient tree trunks or hauled up on rocks, people in twos and threes were appearing between the trees on the portage, everyone was greeting everyone else and exchanging the week’s gossip.

My mother smiled and waved at those she knew (which was all of them) but the person she was really hoping to see was a boy. His parents had a cottage on the northern branch of the lake. They’d been there since 1917 and were among the first cottagers. My mother’s family had started spending their summers on the lake the previous year, but it wasn’t until 1927 that they began building their own cottage, a big, airy, comfortable place with a cathedral ceiling, a huge stone fireplace and a veranda big enough to play tennis on. By the summer of 1928 it was finished, all bar the shingles on the roof. That was where my mother got to know the boy—his mother had sent him across the portage to help shingle the roof. Of course, she’d seen him at church for years, but the roof was where they got to know each other, looking out over the still, quiet lake, shattering the silence with their hammers and nails. The roof was steep and the house was built on a massive mound of granite; if they’d fallen off they’d have broken every bone in their bodies, but they didn’t fall off.

And now, finally, here he came, with his sister and their parents. He smiled when he saw my mother. She would have beamed back. He was shy and very quiet (she was neither) and had absolutely no idea that he was destined to be my father.

They were an odd match: he would become a scientist—he thought with his brain, while my mother thought with her heart; he was cautious, reserved, socially awkward, she was spontaneous, passionate, articulate, funny. But they did have things in common: both were from respectable, churchgoing families with similar values (socially conscious, left-leaning, strong believers in the value of education); both families were from farming stock, but by dint of much family sacrifice had escaped the drudgery of the farm (my father’s father was a university professor, my mother’s a minister, formerly Presbyterian, by then moderator of the newly formed United Church of Canada), and both had inherited from their parents a profound and fathomless love of the landscape of the Canadian Shield, and in particular, this small lake.

When my mother was here, she was utterly and completely happy. When my father was here, he felt connected to infinity.

***

Of course, what is now called “cottage country” isn’t and never was the North—if you look at a map it’s scarcely even the Middle—but to those from the South it felt like it. It was a long way short of “tamed” back then; you could only get there over roads that in places were right on the edge of impassable, and once you reached the lake the road ran out and you had to transfer everything to a rowboat or canoe for the long haul up the lake in the gathering dark. Getting there took determination, planning and time, and as a consequence it was nearly empty. The silence, the peace, were indescribable.

By the time I came along the roads were somewhat better and the drive to the head of the lake had shrunk to a mere eight hours. Still a long time, with six of us in the car, myself a buffer between my two older brothers on the back seat, my younger sister squashed between our parents in the front, the trunk and footwells jammed with essentials to see us through the summer, nothing to see out of the windows but fields and fences, nothing to do but bicker and whine. I pity our parents. It must have been hell.

But gradually, as the day wore on, the soil got thinner and the fields began to give way to meadows bounded by trees, with rounded grey shapes of granite breaking the surface here and there like whales. Then the whales began to take over and the meadows were merely patches of scrubby grass between the rocks and forests. Now and then a pond or small lake glinted through the trees. We children fell silent, gazing out of the windows, remembering the silkiness of the water, the feel of warm, rough, lichen-covered granite under our feet.

I remember those feelings as a kind of ache, a longing, deep in my bones. I feel them still, and so, I know, do my siblings. It turns out that along with fair hair, blue eyes and a tendency towards anxiety, all four of us have inherited that same profound, unreasoning love for the landscape that brought our parents together.

***

It was my mother’s parents’ cottage we inherited, that huge old place set high on the rock, its wooden frame scarcely visible among the trees. Land up there being dirt cheap, we had a lot of it: four rocky points with three bays between them and an enormous lake-frontage. The cottage itself was on the basic side: no electricity, a wood stove, water by bucket from the lake. Oil lamps, which served to emphasize the depth of the surrounding darkness. An outhouse, down a steep rocky path, deep in the woods (meaning a hundred yards from the house, but at night, if you’re small, that’s deep). I was afraid of bears. No bears had been seen in the area in living memory but that meant nothing. I was also afraid (still am) of the giant spiders that squatted in the corners and—much, much worse—under the toilet seat. My brothers, being brothers, carved a huge one, extraordinarily life-like, into the seat itself. It is still there.

As I recall, on the first visit of the year the outhouse smelled of pine gum, well-rotted wood and decaying leaves. Thereafter, needless to say, it smelled of outhouse. I didn’t like it then and I don’t like it now. But I loved absolutely everything else.

Off the largest point of land there was an island, near enough to swim to, large enough to pitch a tent on. We rented it for, I think, a dollar a year. I remember finally being allowed to join my brothers camping there overnight. (My sister, being six years younger, wasn’t allowed, which made it all the sweeter.) I remember one morning discovering that we’d left the lid off a jar of honey and a mouse had drowned in it; I remember my eldest brother swimming after a water snake which grew tired of the chase and swung around and bit him on the thumb. Which turned black, but didn’t, in the end, fall off.

But mostly my memories are not of specific events but of the place itself; the way the mist lifted slowly off the lake in the early morning, the smoothness of water sliding over your skin (skinny-dipping in a northern lake is a joy like no other), the clear looping call of the whippoorwill as you lay in bed in the darkness. I may have been among the last generation to hear that song. It is gone now. The loon has hung on, though. If there is a sound of the North, it is the loon’s strange, sad call.

I don’t think I knew it was beautiful back then—the very young don’t judge things in that way—but I knew it was part of me. I grew up thinking that the cottage was our “real” family home, despite spending most of the year in Southern Ontario. Our two sets of grandparents had met each other on that lake, our parents had spent big parts of their childhood there. They had fallen in love there—without the lake we wouldn’t even exist. It was as close to an ancestral home as a Canadian can get.

Childhood passed. When I finished university, I went to England for a holiday and fell in love with an Englishman. We got married at the lake, standing under a tree on a slab of three-billion-year-old rock. My husband’s entire family, city born and bred, flew over for the event.

My husband fell in love with it on the spot. Perhaps he knew he had to. In due course, we brought our children there, and then our grandchildren. It has changed, of course. Not the cottage, the cottage is exactly the same—still no road in, no electricity, no running water, an outhouse well-stocked with spiders. And not the lake, the lake is as beautiful as it has always been. It’s just that it is no longer peaceful. There are many, many people now, and many, many speedboats, with 200- or 300-horsepower engines. I do my best not to notice them. Late September is a good time to go. Then, particularly mid-week, you can catch glimpses of how it used to be. You still hear the loons.

Sometime in the course of all this I began to write the book that became Crow Lake. I’ll leave you to guess where it was set. The story required isolation, though, somewhere remote and still, and also the sense of community that I remembered from our “other” home, a small farming community in Southern Ontario. It is now so hard to believe that the Muskoka area could ever have answered that description that I mentally picked it up and moved it several hundred miles further north, where stillness can still be found, deep within the vast and beautiful landscape that I have carried with me the whole of my life.

So then: why do I write about the Canadian Shield? Simple. When I write about it, I’m there. It’s a way of going home.

[rdm-gallery id=’1605′]