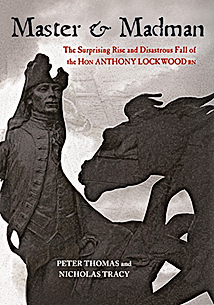

REVIEW: Master and madman: The surprising rise and disastrous fall of the Hon. Anthony Lockwood RN

Book by Peter Thomas and Nicholas Tracy

Share

Canadians prefer to maintain a prosaic view of their politics. We tend to ignore the fact our longest-serving prime minister communed with his dead mother, or that there was once a premier of British Columbia named Amor De Cosmos. But we simply don’t know about Anthony Lockwood. On June 1, 1823, Lockwood, a member of New Brunswick’s ruling Executive Council, dictated a proclamation in Fredericton’s public square declaring he was overthrowing the government. He then galloped through the village of 1,700, waving his pistols and threatening to kill his enemies. His one-man coup d’état failed when the high sheriff arrested him. Lockwood was declared mad, and later left for England to spend the rest of his life in and out of asylums.

Canadians prefer to maintain a prosaic view of their politics. We tend to ignore the fact our longest-serving prime minister communed with his dead mother, or that there was once a premier of British Columbia named Amor De Cosmos. But we simply don’t know about Anthony Lockwood. On June 1, 1823, Lockwood, a member of New Brunswick’s ruling Executive Council, dictated a proclamation in Fredericton’s public square declaring he was overthrowing the government. He then galloped through the village of 1,700, waving his pistols and threatening to kill his enemies. His one-man coup d’état failed when the high sheriff arrested him. Lockwood was declared mad, and later left for England to spend the rest of his life in and out of asylums.

Who was this guy? Thomas, a professor of English at the University of New Brunswick who died in 2007, and Tracy, a UNB naval historian who completed the book, had no easy task in finding out. In part that was because Lockwood rose from humble, poorly documented origins to the heights of colonial society, and in part because he seems to have destroyed—in his madness or out of revolutionary fervour—many of the official documents of his career. Yet enough remains to paint a portrait of his 25 years in the Royal Navy, spanning the French wars and the War of 1812. Lockwood was commended for bravery against the French, was present at the famous Spithead Mutiny in 1797, was shipwrecked and imprisoned in France, and did a three-year stint as marine surveyor of Nova Scotia and the Bay of Fundy. He was, in short, an accomplished man of his revolutionary times, and the authors—neutral about the exact mix of disease and ideology that motivated him—convincingly argue, in this intriguing look at a little-known corner of Canadian history, that Lockwood’s grand gesture on that spring day in 1823 was “both mad and meaningful.”