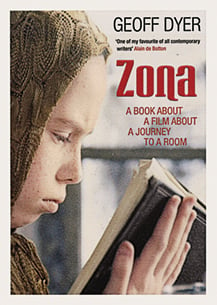

Any writer reading Zona, especially a film critic, will likely be stricken with envy. British writer Dyer has done the authorial equivalent of getting away with murder: he’s devoted an entire book to a rambling essay on a somewhat obscure Russian art film, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979). To summarize Stalker in a sentence, rather than 228 pages, it’s a metaphysical journey about three men in a bar (Stalker, Writer, Professor) who travel through a postwar wasteland of rusting artillery into a puddled wilderness called the Zone, and more specifically the Room, a grail-like gulag where all one’s wishes come true.

Any writer reading Zona, especially a film critic, will likely be stricken with envy. British writer Dyer has done the authorial equivalent of getting away with murder: he’s devoted an entire book to a rambling essay on a somewhat obscure Russian art film, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979). To summarize Stalker in a sentence, rather than 228 pages, it’s a metaphysical journey about three men in a bar (Stalker, Writer, Professor) who travel through a postwar wasteland of rusting artillery into a puddled wilderness called the Zone, and more specifically the Room, a grail-like gulag where all one’s wishes come true.

The film left a radioactive imprint on Dyer’s psyche—eventually he lets drop that around the time he encountered it, he was ingesting a lot of LSD and magic mushrooms, while immersing himself in cinema. Dyer conducts a shot-by-shot tour of Stalker, but Zona is not some microscopic act of cinephilia. He doesn’t revere the film. Instead, he marvels at it, argues with it, makes fun of it—and basically uses it as a daydream machine to launch flights of digression and memoir. As footnotes start crowding out the text, Dyer’s tangents skip from Kafka and Wordsworth to Bergman and Tarantino, from his love for quicksand to the aesthetics of Chernobyl, from his wife’s resemblance to Natascha McElhone to his unfulfilled desire for a threesome. A rotary phone rings in the film and prompts an aside on the evolutionary decline of the index finger and the ascendancy of the texting thumb.

It’s all great fun, and astute in the bargain. Like a literary love child of Pauline Kael and Henry Miller, Dyer strays from his subject with guiltless delinquency, but never loses sight of it. As he sifts through Stalker’s archaeological layers, puzzling over the point of the movie—and his book—he concludes: “If someone will deign to publish this summary of a film that few people will have seen, that will constitute a success far greater than anything John Grisham could ever have dreamed of.” Immodest but true.