The best books to read this winter

From the sex lives of First World War soldiers to the stunning new novel from Esi Edugyan, this list offers a seasonal banquet

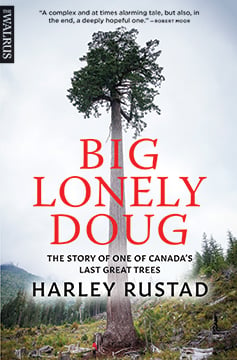

Harley Rustad, author of ‘Big Lonely Doug: The Story of One of Canada’s Last Great Trees,’ stands next to Doug, which was saved from a clearcut (Melissa Renwick)

Share

Fall and winter are the busiest times in the publishing business. It’s also when inclement weather begins its assault, so people are more likely to stay indoors and settle in with a great book, and it’s when they buy new titles for gift-giving over the holiday season. Here are 15 new books to keep you and yours company during the Canadian winter.

Non-fiction

ALL THINGS CONSOLED

A good novelist requires a “sliver of ice” in her heart, British writer Graham Greene once remarked, meaning the willingness to portray emotional truth even when others see it as betrayal. True enough, but what if the novelist turns to memoir and the characters are no longer inventions (with a certain familiarity), but actual family members? Giller Prize-winning author Hay faces that issue in her account of her parents’ last years, when the rapid deterioration of their health, both physical and mental, threw Hay’s life and those of her siblings into turmoil. She responds with careful but stark honesty. Her four years as primary caregiver were exhausting, disorienting and often depressing, while her attempts to understand her family pulled buried pain and grievances to the surface. It’s familiar territory for increasing numbers of Canadians as the population ages, and it’s all unflinchingly laid out in this intense memoir.

—Brian Bethune

THE SECRET HISTORY OF SOLDIERS

Historian Cook’s newest delve into the Great War is not, despite what cynics might assume from the title, entirely about sex. The book doesn’t shy away from the topic, of course, nor could it, given that the Canadian army had the Western Allies’ highest VD rates—at one time, a staggering 29 per cent. But there was much else to occupy soldiers when they weren’t focused on staying alive. Above all, as participants in the first mass war after the arrival of mass literacy, they wrote: songs, theatrical productions, trench newspapers, diaries and 85 million letters. Composed with one eye on the censors, the letters reveal a kaleidoscope of aims and emotions—some lied to reassure families, others were as truthful as possible to discourage younger brothers from enlisting. Many, perhaps most, as Cook persuasively sets out, represented the soldiers’ attempts to make sense of their experiences.

—Brian Bethune

BIG LONELY DOUG

Man meets tree: there is a lot of ground covered in Big Lonely Doug, Harley Rustad’s account of one of the last great trees in Canada, including the contentious history of logging and anti-logging protests on Vancouver Island. But the crux of the story lies in the moment in 2011 when Dennis encountered Doug. The tree, 70 m tall, was spectacular, the man more ordinary. But Dennis Cronin, a forest engineer mapping what would soon be clear-cut forest, did an extraordinary thing. For reasons he later articulated as, “Because I liked it,” Cronin wrapped Doug’s 12-m circumference with ribbon bearing a precise order for the fallers who would come after him: “leave tree.” Soon Doug stood alone in a clear-cut wasteland, about to embark on a new stage in its thousand-year life. That’s when Rustad’s absorbing story of how the human fixation on individuals turned one tree into an icon of both ecotourism and resource extraction really picks up steam.

—Brian Bethune

THE LIBRARY BOOK

The spine that supports Susan Orlean’s marvellous book about the place libraries hold in our cultural imagination is the fire that destroyed Los Angeles’s Central Library on April 29, 1986. A monster of its kind, the blaze reduced 400,000 books to ash, while another 700,000 were badly damaged by smoke or water or both. The Library Book’s superbly nuanced exploration of the fall and rise of the Central Library—the services it provided, the chronic underfinancing that crammed two million volumes into a known firetrap meant for half that number, the 50,000 Angelenos who showed up the day the renovated city jewel reopened six years after the fire—establishes one unmistakable truth. Widely expected to be one of the major casualties of the digital age, contemporary libraries are flourishing perhaps more than ever: society values the common space of the cultural depository as much as its contents.

—Brian Bethune

EREBUS

In his post-Monty Python life, Michael Palin, the member who sold the dead parrot and sang the lumberjack song, has become a popular travel writer. It’s a career that meant Palin—already aware of HMS Erebus’s other polar expedition, its highly successful 18-month exploration of Antarctica—was galvanized by the 2014 discovery of the wreck of the command ship in John Franklin’s doomed Arctic expedition. Palin’s response is an extraordinary book: part biography of a ship, part study in courageous folly. The little-known tale of the southern voyage, based on copious surviving records, is enthralling, but it’s Palin’s refusal to speculate on the thoughts and emotions of the 129 men aboard Franklin’s two ships before the last of them died that gives Erebus an eerie resonance. Franklin’s crew passed on their last letters to their homeward-bound supply vessel on July 13, 1845. Then they sailed off, into silence and 150 years of endless speculation, neatly summed up by Palin.

—Brian Bethune

DEFYING LIMITS

It might be de rigueur for astronauts to pen memoirs when they put down their spacesuits, but that’s no bad thing: even those who aren’t governors general or celebrity polymaths have doubtless led interesting lives. Raised in Montreal, Williams became self-reliant at an early age—“When you’re a 10-year-old kid building fires in the woods and playing in streams, it’s up to you and your pals to figure out the important things.” He went on to save lives as an emergency physician, fly planes, scuba dive, orbit the Earth twice while battling cancer in between, have kids, found a hospice and write this book. Williams’s story shows off his infectious joie de vivre, and if the narrative at times feels thin—one wishes he’d flesh out the conflicts he must have faced along the way—perhaps this is only natural. You can’t shape the future by dwelling on the past.

—Mike Doherty

THE SPY AND THE TRAITOR

In July 2015, the British agents who had smuggled Oleg Gordievsky—a KGB colonel turned British spy—out of Russia in 1985 held a 30th-anniversary reunion with him, and presented the 76-year-old Russian with mementoes of his escape, including a baby’s diaper. Macintyre has been crafting exceptional espionage histories for years, but he’s outdone himself here, especially with the adrenalin-filled description of Gordievsky’s desperate run to the West, when a soiled diaper, strategically dumped beside his hiding place, threw off sniffer dogs and may have saved his life. Gordievsky was KGB royalty, the son and brother of spies and an agent runner in Denmark, when disillusionment led him to work for MI6 in the 1970s. In Macintyre’s account, perhaps no one since Igor Gouzenko himself supplied more priceless information about Soviet operations, aims and fears. Or ever provided so enthralling a true-spy story.

—Brian Bethune

Fiction

WASHINGTON BLACK

The most celebrated Canadian novel of the literary season, Washington Black has been nominated for the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the Man Booker. Set in the 1830s, it follows the journey of a black boy, a gifted illustrator, who escapes slavery in Barbados by means of a hot-air balloon. He is accompanied by his white mentor, a scientist and abolitionist, who suddenly abandons him. Alone in a ruthlessly racist world, Washington seeks a place where he can live in peace and practise his art. He is reminiscent of Hieronymus Falk, the hero of Edugyan’s previous novel, the Giller-winning Half-Blood Blues: he is a genius thwarted by the racism of his era. The author’s meticulous rendering of his story combines the profundity of Melville with the sprightliness of Dickens, and often feels stingingly relevant.

—Donna Bailey Nurse

READ MORE: Esi Edugyan on why readers can’t get tired of books about slavery

BEIRUT HELLFIRE SOCIETY

Set in Hage’s native Beirut in the early days of the Lebanese Civil War, the novel, shortlisted for the Governor General’s and Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction prizes, follows 20-year-old Pavlov. After his undertaker father’s death, Pavlov assumes his place in caring for Beirut’s “orphan” corpses—the atheists, gays, prostitutes and others denied decent funeral services in a religiously conservative society. Pavlov becomes a kind of Charon to his marginalized community, listening to their stories—fantastical or heart-rending or both—while they are alive, and ferrying their bodies to their desired ends after they die, even if it requires secretly exhuming them from where their families have buried them. Full of bleak humour and gem-like sentences—“Their breath reeked of killing,” Hage writes of Pepsi-drinking sectarian fighters outside a grocery store—Hellfire is about death, of course, but not really about war. In this bleakly beautiful novel, that’s just another of the thousand natural shocks our flesh is heir to.

—Brian Bethune

READ MORE: In ‘Beirut Hellfire Society’, Rawi Hage returns to war

UNSHELTERED

The first novel in six years from Poisonwood Bible author Kingsolver implies that if the arc of the moral universe bends anywhere—pace Martin Luther King—it turns back upon itself. The book’s two narrative threads, told in alternating chapters, depict families who live in Vineland, N.J., in 1875 and 2016, and who face similar problems. Nineteenth-century schoolteacher Thatcher Greenwood falls out with Vineland’s founder, real-life historical figure Charles Landis—a charismatic, teetotalling real estate developer who distrusts science and believes violence toward journalists can easily be justified. One hundred and fifty years later, Willa Knox is an out-of-work 21st-century journalist whose dying father-in-law racks up medical bills as he cheers on Donald Trump’s presidential run. Both protagonists trade ideological blows with members of their own families. Often, their conversations feel like stage-managed debates, but Kingsolver is a skilled observer of human nature who suggests that ultimately, confrontation won’t help her divided country move forward.

—Mike Doherty

WOMEN TALKING

Between 2005 and 2009, a group of Mennonite men regularly gassed households into unconsciousness in their remote Bolivian colony. They would then go inside and rape the girls and women, hundreds of them over the years, from three-year-olds to the elderly. That’s the backdrop to Women Talking by Toews, born and raised in the Mennonite town of Steinbach, Man. Her fictional take, nominated for a Governor General’s Literary Award, is set after the rapists have been caught, when the other men have left the colony to go bail them out. Those women who do not want to yield to the colony elders’ demand to forgive and forget gather in a hayloft to decide, for the first time, their own fate: stay or go? Over two days, the women pick apart the issues, practical and moral, that confront them, and pick at wounds that reach much further into the past. Very little happens and everything changes in this mesmerizing story by one of Canada’s finest novelists.

—Brian Bethune

MACHINE WITHOUT HORSES

Humphreys has been blending her writing into “hybrids”—mixtures of fiction and non-fiction—for years now, to critical and popular approval. Most of those books, though, like 2017’s The Ghost Orchard, began on the non-fiction side, where the popularity of “creative non-fiction” has led readers to value the adjective as highly as the noun. Humphreys’s new hybrid novel—the story of Megan Boyd, a real-life salmon fly dresser in the north of Scotland who died in 2001—arrives without that path-breaking preparation. The first half of the book features the author ruminating on why Boyd’s life resonates with her and how best to depict it fictionally; only the second half holds a novel about Boyd. Those for whom the purpose of reading is uninterrupted immersion in another world may find Machine jarring. Yet Humphreys’s beguiling prose is as good as ever, and her low-key melding of process and result ultimately proves fascinating.

—Brian Bethune

TRANSCRIPTION

There is an afterword to this book in which Atkinson seems set to justify its mix of fact and fiction, before losing her patience. “I am fiction’s apologist,” she writes unapologetically, and for every historical fact in this book, “I made something up.” Fair enough, and exquisitely apt for a brilliant spy novel. Set mostly in London, it opens in 1981 as Juliet Armstrong lies dying, near where another “sacrificial virgin”—that would be Lady Di on the eve of her wedding—was being prepared to serve the nation’s needs. But the story, full of whiplash twists, is soon in 1940, when 18-year-old Juliet is recruited to MI5. In Atkinson’s deliberate and manipulative hands, spy stories are simply regular fiction on steroids. Ordinary characters guard their deepest secrets well; for spies, there are lies, damned lies, the lies they tell other spies and, finally, the lies they tell themselves.

—Brian Bethune

KILLING COMMENDATORE

A mysterious figure tells Killing Commendatore’s unnamed protagonist that when it comes to artistic inspiration, “What is important is not creating something out of nothing,” and that he needs to “discover the right thing from what is already there.” He might be describing Murakami’s own process: the celebrated Japanese maverick keeps recombining his favourite idiosyncratic tropes to unexpectedly powerful effect. So too with his latest tale of an emotionally cocooned man who’s obsessed by classical music on vinyl, and to whom some very weird things happen. This time out, a career portrait artist unlocks inspiration when he moves into a dying master’s old house and communes with a violent painting he finds in the attic. Where the novel’s predecessor, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, was rather drab, Killing Commendatore is at times tense, creepy, absurdly funny, self-aware and baffling—and engrossing throughout. Late Murakami by way of late David Lynch.

—Mike Doherty

THE KINGFISHER SECRET

In October 2016, a Montreal tabloid journalist has wrangled an interview with a porn star who will talk about her dalliance with Anthony Craig, who may well be elected U.S. president in a month. But Grace Elliott’s boss buries the story and sends his reporter to Prague to seek out Craig’s Czech ex-wife. Soon Grace has a new scoop—a sexpionage story about a KGB-trained woman marrying into the American elite—that will blow the U.S. election apart. If, that is, she lives long enough to get it into print. The Kingfisher Secret is, of course, one timely thriller, based as it is on Donald and Ivana Trump while Robert Mueller’s Russia-ties investigation is reportedly grinding to an end. And quite entertaining to boot. The author has a lot of fun with names—the porn star, Stormy Daniels in real life, is here Violet Rain—though one of his choices may have outed his nationality. Who but a Canadian would name his protagonist after Justin Trudeau’s grandmother?

—Brian Bethune