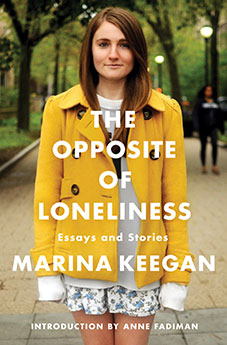

THE OPPOSITE OF LONELINESS: ESSAYS AND STORIES

THE OPPOSITE OF LONELINESS: ESSAYS AND STORIES

By Marina Keegan

In the essay “The Opposite of Loneliness,” for the 2012 graduate issue of the Yale Daily News, Marina Keegan chides her fellow classmates: “Some of us have focused ourselves. Some of us know exactly what we want and are on the path to get it: already going to med school, working at the perfect NGO, doing research. To you I say both congratulations and you suck.” One glance at Keegan’s CV, and most would agree that she “sucked,” too: Harold Bloom’s research assistant, internship at The New Yorker and The Paris Review, a musical accepted to the New York Fringe Festival and a post-graduation job lined up at The New Yorker. Yet, in the essay, Keegan admits to being “lost in a sea of liberal arts,” while convincing herself and her peers, “We’re so young, we’re so young. We’re 22 years old. We have so much time.”

Tragically, Keegan died in a car crash five days after commencement, at the age of 22. In the wake of her death, her call-to-arms essay went viral: “I plan on having parties when I’m 30. I plan on having fun when I’m old.”

This collection of Keegan’s writing, pulled together by her parents and teachers, includes the title essay, some short stories and non-fiction pieces she wrote during high school and while at Yale. Author Anne Fadiman (Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader) contributes a deeply affecting introduction, describing her former student as “brilliant, kind and idealistic,” while also “more than a little contrarian.” This is not a case of posthumously romanticizing a mediocre talent. Keegan’s writing is shockingly good, especially her mastery of first-person fiction. Her characters—such as the woman who reads to the blind while naked, the university student who’s been called upon to eulogize a guy she was casually seeing, and a young woman who may or may not have left her boyfriend over a game of Yahtzee—not only remain with, but haunt, the reader. If only each story were just a few pages longer, you might figure out their motives to better understand these fascinating new acquaintances.

Fadiman’s explanation of why Keegan was such a rare find resonates throughout the collection: “Many of my students sound 40 years old. They are articulate but derivative, their own voices muffled by their desire to skip over their current age and experience, which they fear trivial . . . Marina was 21 and sounded 21: a brainy 21, a 21 who knew her way around the English language, a 21 who understood that there were few better subjects than being young and uncertain and starry-eyed and frustrated and hopeful.”

SHANDA DEZIEL