Welcome back, Ed the Happy Clown

Chester Brown’s influential graphic novel has been reissued and, rest-assured, is just as rewarding 20 years later

Share

Last year, Toronto cartoonist Chester Brown raised eyebrows—and his profile—when he released his fourth graphic novel, Paying For It, a memoir of his life as a john that proffered a conscientious and (mostly) well-argued rationale for why prostitution should be decriminalized in Canada.

Last year, Toronto cartoonist Chester Brown raised eyebrows—and his profile—when he released his fourth graphic novel, Paying For It, a memoir of his life as a john that proffered a conscientious and (mostly) well-argued rationale for why prostitution should be decriminalized in Canada.

It was a small sensation: the book received mostly positive reviews, and sparked heated debate in the wake of Ontario Superior Court Justice Susan Himel’s controversial decision to strike down the provincial laws criminalizing prostitution. The graphic novel also provided a punctual reminder of Brown’s uncanny ability to create thought-provoking comics that transcend the medium seven years after his best-selling Louis Riel biography brought him national attention from non-comics readers.

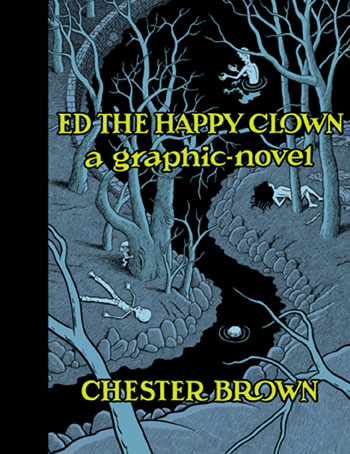

With the iron still hot, literary Montreal comics house Drawn & Quarterly decided to strike again, reissuing Ed the Happy Clown, the book that defined Brown’s early career—and won the Harvey award for Best Graphic Album in 1990—in a hardcover, note-appended edition. Since 1989, when the graphic novel was first published by now-defunct Toronto comics publisher Vortex, it’s been a cited influence for countless giants in the comics industry, including Seth, Chris Ware, Craig Thompson, Dan Clowes, Bryan Lee O’Malley and Anders Nilsen.

Over 20 years later, reading Ed the Happy Clown is just as rewarding. The story, which revolves around the exploits of Ed, the eternally white-faced, red-nosed titular character, plus a female vampire, a penis with the head of an American president, a man whose bowels move indefinitely, a hot-headed anarchist, some scientists, government workers and hordes of an alien race called Pygmies (whose depiction a now-mature Brown regrets), is the sum of those parts — always manic, often offensive, and at times jumbled — and yet it remains a fascinating read, both by itself and in the context of Brown’s now-illustrious career.

Ed’s turbulent plot is characterized by unpredictable twists and turns symptomatic of Brown’s early, improvisatory writing methods. From 1981 to 1985, he was drawing the short, non-linear beginnings of Ed in Yummy Fur, his self-published mini-comic. At the time, Brown had no intention of tying together these crude, and seemingly disparate strips, but by 1986, Vortex had picked up YF as a monthly, 24-page comic series, and Ed was the main reason. That the character’s storyline would become his first graphic novel was still unbeknownst to Brown, so while he continued to serialize the story—fleshing out the plot and characters—he finished each comic without a plan for where he’d go next.

Though this narrative turbulence makes summarizing Ed near impossible — and would, after all, ruin the fun of reading it — it hardly matters; the novel’s pleasures lie as much in its subtle details as they do in its roller-coaster plot. By 1986, (page 40 and onward in this edition), Brown is able to communicate, in wry little one-liners peppered throughout the comic panels, the social and political commentary that characterize the book. Despite the fact that Brown deprecates his younger self through his notes for his immaturity and ignorance, his little jabs at Toronto police, religion, science, sexism, and homophobia remain hilarious and incisive. Indeed, even the silliest aspects of Ed — the excessive violence, the scatology, an argument between two vampire-killing twins over whether they’ve chosen the right career path — reveal a winking Brown’s acute understanding of human avarice, exploitation, and uncertainty, respectively.

Brown’s extensive notes at the end of the book are an added bonus to this edition. They’re less intensive than those in Louis Riel and Paying For It, but just as interesting, and they offer authorial insight into the novel itself while simultaneously providing an autobiography of the years Brown spent writing Ed. Fans of Brown’s work will enjoy the way these notes illuminate this period of his life, but all readers will enjoy the way they illuminate this period in Canadian comics history. One particularly fascinating passage finds Brown discovering, in 1992, “a new model … developing for narrative-print-cartoonists — the graphic-novelist model.”

In the early ‘90s, the graphic novel was still emerging as a literary phenomenon, and Brown, now an iconic figure in Canada’s literary landscape, was at the forefront — and still is.