Why the long-ago murders of two tycoons in Canada haunt us still

Unlike good crime fiction, true crime stories are often more lurid, and document shoddy police work

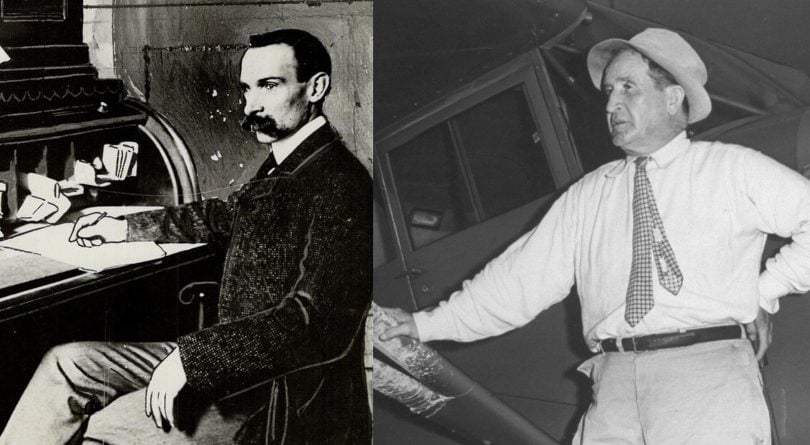

Sir Harry Oakes leaning against an airplane with his hand propped on his hip. (David E. Scherman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Share

RIGHT: Sir Harry Oakes leaning against an airplane with his hand propped on his hip. (David E. Scherman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

One hundred years ago, on Dec. 2, 1919, 53-year-old Ambrose Small disappeared, never to be seen again. It was the day after one of Toronto’s most prominent businessmen had sold his booking agency and his stake in a chain of live theatres for a hefty $1.75 million (about $23 million today), and about two weeks before anyone began seriously looking for him. The lack of concern arose in large part because Small—not exactly a pillar of Toronto the Good in either his sharp-edge business practices or his private life—had a history of disappearing for lengthy periods, visiting racetracks or a mistress. But another reason was the fact that a century ago it was still easy and common to “go missing for several days at a time,” says journalist Katie Daubs, author of The Missing Millionaire, in an interview. Getting out of “the modern mindset of emails and cellphones,” she adds, was a crucial first step in re-creating Ambrose Small’s world.

And recreate it Daubs does, in a lovely, nuanced work of social history. The Toronto of 1919, which the forces of industrialization had transformed completely over the course of Small’s lifetime, was haunted by the ghosts of thousands of the “missing,” young men mowed down in the Great War. It was also a golden age for what Maclean’s, looking back 30 years later, politely called “an unusual number of investigators with methods so mysterious that they completely baffled police”—meaning pseudo-scientists, psychics and con men of all stripes. One was Maxmilian Langsner, a self-styled “Viennese criminologist” (he was neither) who announced, in 1928 no less, that he had located Small’s burial site through his “thought-wave system” and merely needed funds to unearth the bones and, not incidentally, pay his own hotel bill. That Langsner received any kind of hearing may seem laughable, even in our age of lunatic conspiracy theories, but belief in communicating with the dead was not ridiculous in the 1920s, when Arthur Conan Doyle proclaimed it a “new revelation” sent by God to comfort those bereaved by the war.

READ: Who killed Barry and Honey Sherman? A new book offers fascinating insights.

Daubs also covers the nitty-gritty of the era well, with a sharp eye for details. As a flashy, younger rich man, Small was an early car enthusiast—he tended, in fact, to buy a new one twice a year—and one of his vehicles was among the first in the city, with Small’s chauffeur at the wheel, to strike and kill a pedestrian. And then there’s Daubs’ entertaining account of how Jack Doughty, Small’s private secretary and a chief suspect in whatever happened to the impresario, conducted the 1919 equivalent of those how-to-kill-your-spouse Internet searches that prove so damning in contemporary trials: he asked almost every acquaintance he encountered in the days before Small’s disappearance, “How would you kidnap an abusive employer?”

What Daubs doesn’t do—and couldn’t after all these years, short of a hidden confession emerging—is solve the crime, any more than Charlotte Gray can add much more of an answer in Murdered Midas to the question of who killed mining magnate Harry Oakes in 1943. (Who says Canadian business history is boring?) What true crime writers can do is the same as what crime novelists do: offer social commentary with a puzzle aspect. Two factors tend to distinguish actual crime stories from their fictional counterparts. First, they are often unsolved and the police work, more often than not, is shoddy—in the first of what will likely be a few books about the 2017 slayings of wealthy Toronto couple Honey and Barry Sherman, Kevin Donovan’s The Billionaire Murders, the Toronto Police Service does not come off well.

In Small’s case, Daubs essentially opts for the conclusion reached by the Ontario Provincial Police’s 1936 examination of the record: in all probability, Small’s wife, Theresa, was the brains behind his disappearance (and death), Doughty was the muscle, and investigating police detective Austin Mitchell the useful idiot. As for the murder of U.S.-born Oakes’ murder, the case was bungled from the start by two Miami cops imported into the Bahamas case by the Duke of Windsor, the former King Edward VIII who was governor of the British colony. The mess police made of the evidence was crucial in the acquittal of Count Alfred de Marigny, husband of Oakes’ daughter Nancy, in his trial for the murder of his father-in-law. Just as well, argues Gray, who believes de Marigny was innocent and points a convincing finger at another suspect.

But it’s the second factor that probably most unites true crime stories, especially the cases that generate multiple books and documentaries over the years. They are usually lurid in ways that much very good crime fiction is not, because the best fiction writers are often far more interested in what Ann Cleeves, the prominent British author whose works are the basis of the Shetland and Vera TV series, calls the “social pathologies” that led to the death. That’s why, Cleeves told a packed audience at a Toronto Public Library talk in November, “I tend to just smash [the victims] on the back of the head.” Harry Oakes, however, was struck four times behind his left ear with what may well have been a miner’s hand pick, then doused with insecticide and set on fire in his own bedroom. That’s why Gray can confidently predict that the same combination of “a dead white man who is the epitome of white privilege, a brush with the royal family—actually, a rather seedy ex-king—and a completely delicious unsolved murder” that made the Oakes case “absolute catnip for Fleet Street writers for decades” will see it kept alive for years to come.

Gray opens her absorbing and offbeat book with a lengthy foray into the origins of Oakes’ wealth—his key role in the Northern Ontario gold rush that turned Toronto into the world capital of mining in the 1920s—before turning to the inept officers and the sensational de Marigny trial. But Murdered Midas is at its most original and compelling in the final section, on Oakes’ afterlife. An award-winning historian and biographer, Gray wanted both to let readers in on the tricks of her trade and offer Oakes, a truculent and unpleasant man, some justice. “ It was a very deliberate attempt to be transparent,” she says. “You’re always making choices about what to include and how to interpret the evidence. And there are things you don’t know. This time I wanted to come clean on all that. I know I can tell a story. But now I wanted to show readers how it’s done. Writers can and do shape posthumous reputations with subtle adjustments and sly cuts, so I showed how Oakes’ story has been skewed in the years since his murder.”

For Gray, Oakes is very much “the dead guy in a game of Clue.” So too is Daubs’ Small, in his shadowy way. The victims are the backdrop, entrées to a time and place, in true crime stories as much as in the fictional variety. In both, murder always brings a final indignity: “A corpse,” as Gray quotes Jean-Paul Sartre, “is open to all comers.”