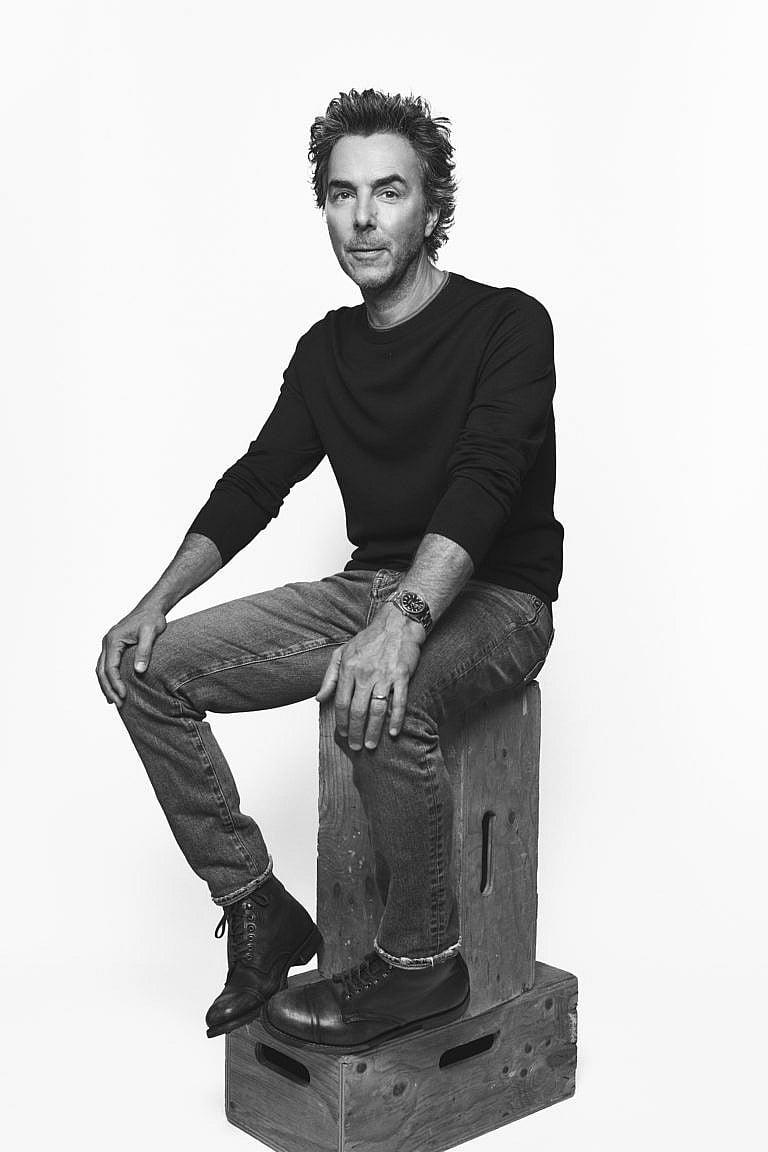

Blockbuster director Shawn Levy is Hollywood’s most reliable hitmaker

In a film landscape rife with strikes, cynicism and, soon, AI, the Montreal-born producer-director is still cranking out cinematic gold

Share

Every night is a blockbuster night for Shawn Levy. Coming up in the ’90s, the Montreal-born director, screenwriter and producer mastered the buttery box-office banger—think Date Night, Cheaper by the Dozen, Night at the Museum and The Pink Panther (Beyoncé’s version). Even now, it’s virtually impossible to escape his creations. Perhaps you’ve heard of Stranger Things? He produced it. Deadpool? He’s partway through directing instalment three. Star Wars? Ha! In development.

Hollywood’s franchise fetish certainly shows no signs of abating, but, lately, Levy’s had to evolve his oeuvre along with a shifting industry, one disrupted by streamers; a new wave of scrappy, Macbook-owning Canadian talents; a contentious SAG-AFTRA strike and, relatedly, AI. Even the crowned emperor of family comedies is wading into more dramatic fare, with this month’s All the Light We Cannot See, a Netflix miniseries based on Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer-winning novel, set during the Second World War. In fact, Levy’s production company, 21 Laps Entertainment, has more than 10 Netflix vehicles in the hopper. He’s going to make it impossible for you not to love them, too.

So much ink is spilled about mega-million-dollar deals, on-set drama and who’s been tapped for what franchise. Directors now seem to get the kind of breathless coverage once reserved for actors. You, however, are maybe the least well-known box-office sure thing. Do you prefer a low profile?

I didn’t set out to be incognito; I just always focused on the making of things more than being known for the making of things. I wanted to direct very badly, very young. I’m proud that I live a scandal-free life. I’m happy not to chase the other stuff.

Between Stranger Things and The Adam Project, you seem to have a knack for sniffing out future hits. Do you look for plot? A particular feeling? What makes you say: “This is a Shawn Levy movie”?

Well, if you’ll indulge a sports analogy, swinging at bad pitches tends to make you miss. I’m always looking for a project with a fundamental humanism—a story that’s anti-cynical. Sometimes, it’s big on inner-child stuff, like: what if museums came to life after dark? There’s the plot, but a movie’s theme might be yearning for agency in a world not of your making. The idea is always bigger than the premise.

You used the term “anti-cynical.” You made your name in blow-out family comedies like Cheaper by the Dozen. “Feel-good” can be a pop-culture pejorative. There’s a snobbery that says if it’s loved by everyone, it can’t be that good. What’s your take?

Even when I was in film school at USC in the mid-’90s, while all of my classmates were making dark, violent Tarantino derivations, I was making Broken Record: a rom-com about a 12-year-old boy and girl who get married to make it into the Guinness Book of World Records. I was always aware of the dismissive attitude toward popcorn populism, but pleasing a crowd is my north star. And, as the world has grown darker, the appetite for warm-hearted fare has increased. Look at Barbie—it’s not a seedy journey. It’s unabashedly escapist.

And Ryan Gosling’s in it.

All Canadian Ryans rule.

READ: The Rise and Fall of a Chinese-Canadian Pop Star

On that subject, you’ve got upward of 10 projects in the works with Netflix, but the partnership everyone wants to know about is your bromance with Ryan Reynolds. So: how did you two meet?

Well, it’s especially weird because neither one of us has many friends. We both have a lot of kids—eight offspring between us. We’re not out there looking for bro-down beer-and-nacho nights; we’re homebodies. About a decade ago, I was making a movie called Real Steel with Hugh Jackman, and he said, “There’s a guy who, if you ever work with him, you’re never gonna stop. It’s Ryan Reynolds.” Then, in July of 2018, I got a text out of the blue: “Hey, Ryan here. What are you doing next year? I think I found our movie.” That was Free Guy.

The film’s about a bank teller who realizes he’s a video game character, right? What sold you on the movie—and Ryan?

I wasn’t a huge gamer, but Ryan said, “The movie has a theme of wish fulfillment in a world that feels disappointing.” As soon as he framed it that way, I knew we thought about movies similarly. We rolled right from that into The Adam Project. Then he said, “You know, they really want me to do Deadpool 3, but I’ll never do it if it’s not with you.” I said, “Are you joking? I’m fucking in. I loved Deadpool before I loved you, Ryan Reynolds!” I actually spent the first half of today with him, starting with a joint workout. That involves me reducing his weight by two-thirds, then doing my set.

Don’t you live, like, 100 yards away from each other in Manhattan?

If I worked on my biecps and threw a stone out my window, it could break Ryan’s.

For so long, Canada’s been banging the “Hollywood North” drum. Between your production company 21 Laps Entertainment, Elevation Pictures, the Ryans and directorial talent like BlackBerry’s Matt Johnson and Emma Seligman of Bottoms, do we even need to chase American clout anymore? We’ve got our own, thanks.

There’s no question that there’s more visibility on our talent—we have a deep bench. (By the way, I straight-up cold-called Matt Johnson after I watched BlackBerry. It’s fun to tell someone you admire their work, even if you don’t know them.) For Canadians, there’s an eternal conflict between chasing Hollywood clout and knowing there are other metrics for success. Decades ago, there was almost a tractor beam pulling me south. The emerging generation isn’t running to the same end zone as I was. They can make a film with independent distribution—in Canada. Sometimes the goal is financial, but now, it’s also about having your piece reach a certain cultural volume.

The traditional studio setup has been upended by the Amazon Primes and HBO Maxes. Have streamers levelled the playing field for filmmakers at all?

I don’t know that they’ve made things more equitable, but the tools of filmmaking have become much more democratized. Films don’t need to be slick or big-budget to get seen. Where the streamers have also increased opportunity is in the sheer volume of content. That didn’t exist when you only had, you know, six theatrical studios.

You touched on technology, which—in addition to compensation—is one of the sticking points in the recent SAG-AFTRA negotiations. Are you tempted to use AI?

As of now, it’s not something I have any interest in. I’m a spectator—along with the rest of the human race.

Have you seen any films that have used AI in ways that impress or intrigue you?

Not yet. I’ve seen it used in visual art at MoMA here in New York, and in some tweets my college-age daughter has shown me. I can’t say that it’s emulating human voice and nuance well at all. By the time this article comes out, though, things could be radically different.

The strike has actors and writers on one side and studios on the other. Directors are an awkward island in the middle. How has that conflict affected you?

Massively. We were in the middle of filming Deadpool 3, and I had to send 500 people home without jobs. The pain isn’t just being inflicted on striking guild members, but the entire ecosystem of the industry: crew and ancillary artists aren’t able to earn a living. It’s brutal. I’m hoping for more equity in the new deals.

READ: How Celine Song’s Past Lives became the surprise indie hit of the year

It’s incredibly difficult to get bigger studios to green-light original content now—that is, movies without already-bankable source material, like comic books. You’ve dabbled in the franchise pool yourself. How do you create anything new when the public (and studios) seem to want more of the same?

I’m answering this as someone who’s working on Star Wars after Deadpool, but I’ve still built the majority of my career on original content, projects that miraculously got made in the absence of—overused word alert—IP. We went to Fox and said we wanted to make Free Guy based on nothing: a new screenplay centring on a video game that’s made up. How do you do that? You pitch your ass off.

You said that you lost your shit when you were tapped to helm the next Star Wars film.

I lose my shit every time I think or talk about it. My younger brother and I would take the 24 bus down Rue Sherbrooke to the Imperial Theatre in Montreal. I saw Return of the Jedi there six to 12 times.

Have you played with any of the toys yet?

I have, but not specifically for the next movie. I directed a Nissan commercial several years ago to shoot a scene with the Millennium Falcon. I can’t even tell you what model we were selling. When something achieves cultural-icon status, like Stranger Things, it assumes a magical totemic power.

It can also resurrect the pop culture of the past. Somewhere, Kate Bush is like, “Thank god for Shawn Levy.”

She’s been very gracious. But I don’t go into any of these things saying, “This is going to be a billion-dollar, three-movie franchise.” I meet so many young filmmakers now who come into a first meeting and want to talk about building a franchise. That’s a presumptuous way to start. It’s mercenary, and I don’t think it fosters good karma.

That said, the projects on your CV share a certain stubborn sunnyness. You’ve said publicly that you didn’t have the easiest childhood—your mom struggled with addiction and you more or less willed yourself toward happiness. Not to frivolously psychoanalyze you here, but…

I was clear that the general sadness that I saw my mom wrestle with for most of my life wasn’t going to be my destiny. I loved growing up in Montreal, but that part of it was like living under a heavy blanket. The minute I could throw that blanket off, I did. I did community theatre in high school, then skipped CEGEP to apply to Yale for drama. Even after I became “family comedy guy,” I founded my company as a step toward a more eclectic workload. “What’s next” has always been axiomatic for me.

I’m curious: how did 21 Laps get its name?

When my first-born, Sophie, was in kindergarten, her school hosted a fundraising jog-a-thon. Sophie was in no way athletic. I was like, “I’ll sponsor her per lap. It’s not going to cost anyone a lot of money!” She didn’t break her stride for the entire jog. By lap 19, I was sobbing on the sidelines. I thought that if the goal of the company is to surprise people, 21 Laps felt like a good name.

Jog-a-thons, man. We need to find another way to raise money.

I have a vague memory of doing a fitness test that involved sit-ups and climbing a rope in front of my peers—cruel activities.

That’s when you find out you’re an arts kid.

That was it.

On pivots: you used to be an actor. You’re even an alumnus of Stagedoor Manor, a prestigious performing arts school in the Catskills—Natalie Portman, Robert Downey Jr. and you. Was there a moment when you realized, Wow, not for me?

At Yale, I got cast as Billy Bibbit in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, opposite a fellow freshman named Paul Giamatti.

Stop.

I did my cringeworthy version of Bibbit’s stutter. Giamatti, meanwhile, is just astonishing as McMurphy. I was like, “Shit, that’s what greatness looks like.” I was too self-conscious to lose myself in acting. Amazingly, by senior year, I was directing Giamatti in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Paul’s dad, Bart—the president of Yale who later became the commissioner of MLB—came up to us after our final performance and said, “You boys are both doing what you’re supposed to.” Like hearing an oracle speak.

I read that your own dad once said, “You’re this big Hollywood director, but you live a Montreal life.” What did he mean by that?

I think it was his way of saying, “I’m glad you didn’t become an asshole, son.”

READ: How this choreographer created the creepy monster movement in The Last of Us

Your non-asshole friend Ryan has mastered side hustles: Aviation gin, Wrexham Football Club and… everything else. Do you see yourself similarly wading into moguldom?

I’ve always had a sweet spot for candy, to a degree that’s probably inappropriate for a middle-aged man. If someone put a pack of Fun Dip or a roll of SweeTarts in front of me right now, we’d have to pause.

Perfect movie food.

Give me some Glosette Raisins and I’m a happy boy.