How this choreographer created the creepy monster movement in The Last of Us

Vancouver’s Paul Becker studied National Geographic, Japanese dance and Jurassic Park to design how the Infected get around

Share

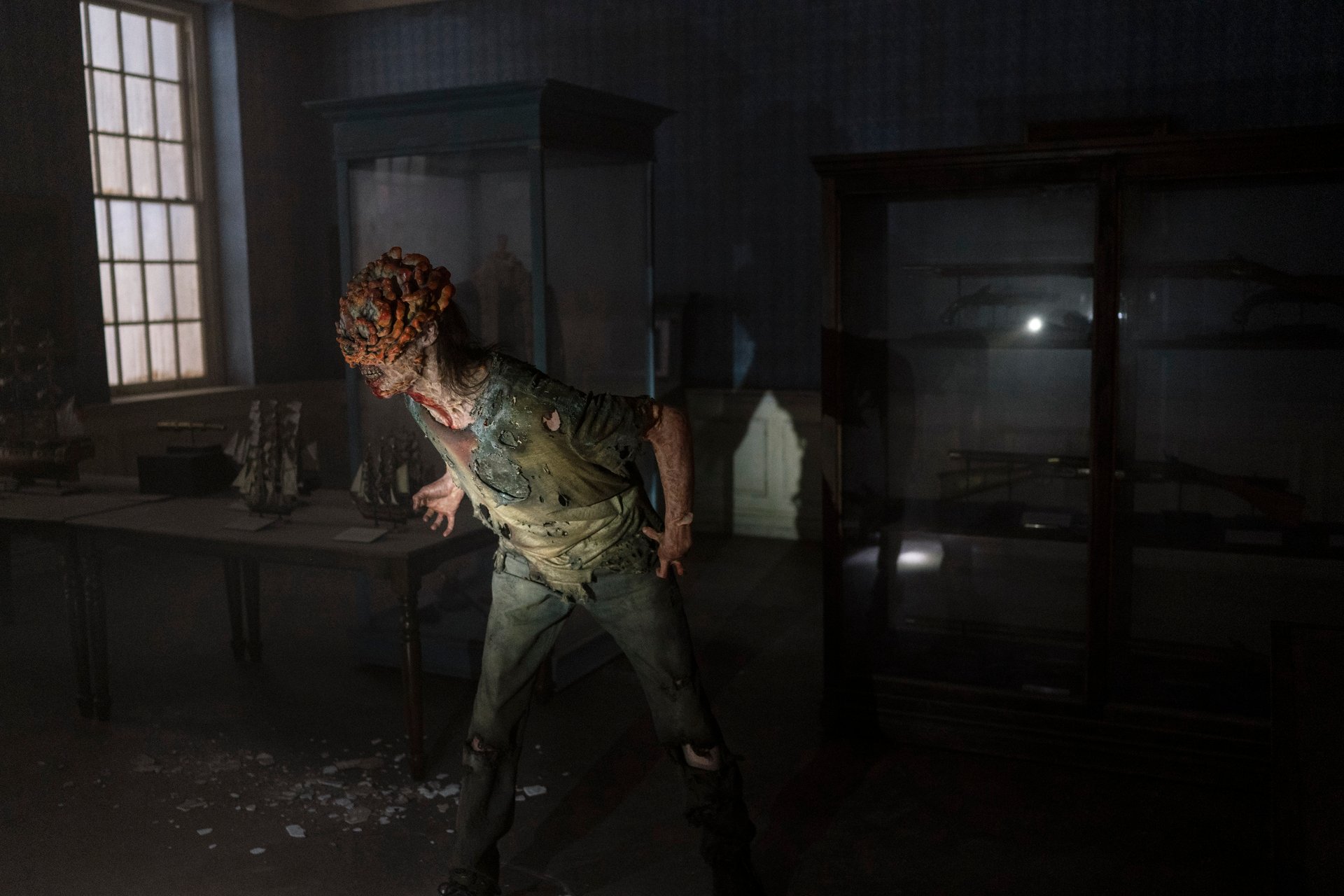

If you’ve been tuning into The Last of Us over the past two months, you can thank Paul Becker for your nightmares. In HBO’s hit series, a mass fungal infection turns humans into a breed of lethal braindead mushroom monsters, triggering a full-scale societal collapse. Becker, a 43-year-old choreographer from Vancouver, was hired to ensure the movements of the infected population were as authentic as they were creepy. His process started with several months of homework: researching the connection between movement and neurological disease and mining the archives of National Geographic. He came up with an erratic, twitchy style of motion that evolves over different stages of infection but should, under no circumstances, be described as zombie-like. We talked to Becker about how he created the now-iconic Clicker choreography.

According to your IMDB page, you’ve spent the last two decades doing choreography on some pretty big movies. How did you get into this line of work?

I started my career as a dancer. I was breakdancing at 13 and later I got into other styles. Even then, I knew I wanted to not just dance, but create. In 2002 I got a job as a backup dancer in the movie Chicago. Rob Marshall, the director, started as a choreographer, and I was inspired by his ability to tell stories through movement. I was a sponge on that set. My big break was a few years later, when I was dancing in a commercial with Kate Beckinsale. It was for a Japanese soap called Lux, and we were shooting in Vancouver. Kate was very upset because the choreographer didn’t show up, and I said I could help. That credit helped get my foot in the door, and in 2004, I booked my first movie, doing choreography for Ice Cube’s Are We There Yet? I’ve been working steadily ever since.

READ: How HBO’s The Last Of Us transformed Alberta into a zombie wasteland

How did you end up working on The Last of Us?

I got a call from Rose Lam, the executive producer. I’d worked with her on A Series of Unfortunate Events with Neil Patrick Harris. She said, “I have a job proposal for you, but it’s pretty unorthodox.” This job didn’t involve dancing—I had to develop a language of movement for these fungus-infected characters who are a huge part of the show. After that conversation, I had a call with Neil Druckmann, who developed the original video game, and Craig Mazin, who created the TV series. They were really committed to getting the details right. I remember they said that with the infected, every movement has to have a reason, which is absolutely my language as a choreographer. I was really excited.

Was monster movement in your wheelhouse before this latest gig, or did you have to watch a bunch of old zombie movies?

This wasn’t my first time working on creature movement. I did Cabin in the Woods, a horror movie where the main characters are attacked by various monsters and zombies. I also did a couple of Wes Craven projects and some of the werewolf movement in the Twilight movies. In a lot of horror, there is a fine line between fear and laughter. For The Last of Us, we really wanted to avoid anything that came across as cartoony or schticky. We actually weren’t allowed to say the word “zombie” on set. That was a rule created by Neil and Craig. Zombies are dead, whereas the infected are still living, but braindead.

How does that play into the way they move?

It depends on their level of infection, which is something we took straight from the video game. There is a big difference between a Runner, who has just recently been infected and is more human-like, and a Clicker, who’s at a late stage of infection, where their whole body and face is covered in mushroom spores. Overall, the movement is twitchy and unpredictable. They can be eerily calm in one moment and then darting at super speed. There’s a marionette-like quality. You see that with the arm movement too, where it’s almost like the arms are being yanked by a cord.

Behind the scenes of the Infected rampage

The Making of The Last of Us, a 30 minute special, now streaming on HBO Max#TheLastofUs #TheLastofUsHBO #TheLastofUsEp9 #TLOU #HBO pic.twitter.com/bLgCojpwmm

— Atom (@theatomreview) March 13, 2023

What were some of your key inspirations?

Neil and Craig explained how all the movements stemmed from a neurological glitch caused by the cordyceps mushroom infection. My task was to figure out how bodies would react, so I hired a team, and we spent about five months doing research. Early on, we found a National Geographic video of ants infected by parasitic fungus spores, which was a key inspiration. Another touchstone was Butoh, which is a Japanese style of dance that’s based on the idea of pushing past socially acceptable movement, so there’s a lot of creepy-looking contortion. And then I researched neurological diseases like Parkinson’s to get a sense of the tremors and spasms that characterize the earliest stages of infection.

We also had to figure out the movement around how the infection spreads, which occurs through these tendrils that come out of the mouth. That movement is almost like a kiss. We had a lot of fun doing these experiments where we would have someone biting into a watermelon to get the mouth positioning exactly right. It seems a little artsy-fartsy, but it was necessary to fully understand every detail—because after I designed the movement, I had to teach it.

There were boot camps to teach extras how to move like the infected. Did you run those?

I ran many of them, although it wasn’t like one big boot camp—we did different training sessions depending on the episode. Sometimes I was working with a particular actor and their stunt double, other times it was groups to prepare for the scenes with mobs of infected characters. When we were in Calgary, we had a space on one of the soundstages that was like a big gym with mats on the floors, so we could be barefoot and play around. I would get everyone to stand in a circle and close their eyes, and then I would guide them into character, starting with their breathing and then the smaller, twitchy movements. One thing that surprised me was that the trained dancers weren’t any better at it than the actors. They often were worse, I think, because they tend to be so aware of their bodies, and there can be this inability to let go, which was essential to what we were doing.

Did you give yourself a cameo?

No, but my daughter, who is a professional ballet dancer and stunt double, was in a few scenes. There was this one set-up where there was a dogpile with 45 infected characters all in full makeup and prosthetics, and she was one of them. We did a rehearsal for that scene where everyone was lying down and twitching. I’d yell the word “sunlight,” and they would go slack, and then I’d yell “cloud cover,” and it was like human popcorn. It was fun, but in the end, they went with a wider-angle shot, so they did the scene in CGI instead.

Is there a scene or episode you are particularly proud of?

The very first time we see the Clickers is in Episode 2, when they attack Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey’s characters in the museum. That was such an important reveal in terms of the franchise and the fan base, so I felt a lot of pressure to get it right. Clickers are fully transformed, so they can’t see. Instead, they use echolocation. We put a lot of work into the first time audiences saw their scream. The Clicker’s arms launch backwards, and their chests push forward. Dinosaurs were a big inspiration, and particularly one scene in Jurassic Park where the little dinosaur lets out this giant scream. One thing I really liked about this show was the subtlety. There are a few big moments, but a lot of the terror comes from the restraint.