Hef’s bosom buddy

Orillia’s Doug Sneyd, a ‘Playboy’ cartoonist for 48 years, spotted Hugh Hefner’s no. 1 girlfriend first

Hef’s bosom buddy

Share

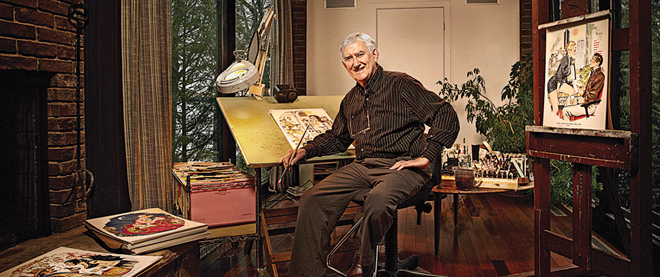

For half a century, Doug Sneyd has worked for Hugh Hefner, publishing more than 450 cartoons in Playboy magazine from his home in Orillia, Ont. Despite that lengthy and ongoing professional relationship, Sneyd and Hefner have met exactly once, at Expo 67 in Montreal, where Hef was opening a Playboy Club nightspot. So it was an especially neat trick when, two years ago, Sneyd, who is 80, managed to introduce Hefner, 85, to 28-year-old Playmate Shera Bechard of Kapuskasing, Ont.—a woman Hefner describes as “my No. 1 girlfriend.” But let’s start this story at the beginning.

You see, Sneyd doesn’t really fit the profile of the Playboy cartoonist, whatever that is. He grew up in staid Guelph, Ont., has lived in small-town Orillia since 1969, was married for 44 years to the same woman—Shirley—and raised four children. He was a seasoned member of the Rotary Club of Orillia, did illustrations for Chatelaine and made a good part of his living supplying the Toronto Star and other papers with thoughtful, often provocative editorial cartoons. A widower since 2001, he met his current girlfriend, Heidi Hutson, a decade ago after a day of golfing. “I don’t know too much about him,” Hutson, 67, recalls a friend saying after they first encountered Sneyd at an afternoon social, “but I think he works for Walt Disney.”

Sneyd didn’t set out to become a Playboy cartoonist—or even a cartoonist at all. Far from it. Yet his sensual, silly, single-panel gags, meticulously executed and vividly coloured for the past 48 years, have become a Playboy hallmark. “He’s an ideal cartoonist for us because he has a good eye, a good sense of humour and is able to draw a very pretty lady,” says Hefner. That is made amply clear in The Art of Doug Sneyd, a lavish coffee-table book published last year with some 270 of his Playboy cartoons. “Oh, yes, I still have my virtue, but I hardly ever use it anymore,” a redhead with a beehive tells a man in evening dress (November 1979). “The way I see it, promiscuity is its own reward,” one woman remarks to another (July 1972). As one dry-as-dust clerk at Library and Archives Canada, which keeps a Sneyd collection, writes in the archive record: “Generally, the cartoons deal with male-female relations and reflect the attitudes towards women and sexual mores held by [Playboy].”

Beyond chronicling the sexual revolution at full tilt, Sneyd has observed, in minute detail, great upheavals in dress, footwear and coiffure. He does not use models, and keeps on top of trends with fashion mags, Playboy pictorials and Heidi’s critiques (of the “those-shoes-are-soooo-out-of-date” variety). The faces, and bosoms, meanwhile, have stayed largely the same with one exception: “I don’t draw boobs like this anymore, they look like torpedoes,” he complains of an early effort. “Just a very lush, realistic style,” says Chris Kemp, a Toronto musician who writes gags (the one-liners under the art) for Sneyd. “All his women are beautiful but there’s an innocence about them, an ingenue quality. They’re never the brunt of the joke.” Sneyd, ever accommodating, tries to summarize his work: “It’s Kama Sutra with humour,” he decides. “I try to make the women as cute and pretty and lovable and believable as possible—and fetching. Like Hefner said: ‘The girl next door.’ I like his philosophy. There’s nothing bad about sex. It’s great. It’s been condemned over the years. And that’s unfortunate.”

Those who don’t know Playboy well won’t associate the magazine with cartoons. But Sneyd became one of the form’s pre-eminent practitioners at a time when Playboy rivalled The New Yorker for cartooning excellence. “The cartoons helped really define the personality of Playboy, as much as any other element, really,” Hefner says. Jules Feiffer, Shel Silverstein, Erich Sokol—all flourished under Hef and Winnipeg-born Michelle Urry, Playboy’s veteran cartoon editor until her death in 2006. “For a long time she was buying better stuff than The New Yorker, especially as the great old era of The New Yorker faded,” says Arnold Roth, a former Playboy cartoonist who, at 82, still appears in The New Yorker. Now the artists of Playboy’s heyday too are mostly dead or faded, and perhaps only the darkly whimsical Gahan Wilson has published there longer than Sneyd. “Sneyd is one of those features you assume will always be there,” says Joe Kilmartin, manager of Toronto’s Comic Book Lounge & Gallery. “The biggest secret about Doug is that he’s Canadian.”

Beyond some very subtle allusions—in one panel a University of New Brunswick diploma is visible, in another a gondola from Mont-Sainte-Anne ski resort—Canada doesn’t figure in his work. Nor does Orillia, where locals slow their boats near his home on Lake Couchiching more because of its newfangled architecture than his job. Still, says Bruce Waite, Sneyd’s friend and lawyer, “Over the years I think he’s captured a few women from Orillia in his cartoons—certainly without naming them. That was a fun thing to wonder: if your wife might end up in one of Doug’s cartoons.” (Sneyd is too polite to say which of his in-laws he later realized was the unconscious model for a recurring character—a heavy-set brothel madam in pearls.)

Yet Sneyd is steeped in Canadiana. By age 19, under the spell of such Maclean’s illustrators as Franklin Arbuckle and Oscar Cahén, he’d begun pitching cover illustrations to Maclean’s. As a freelancer in 1956, Sneyd got a call from an important client, a textbook publisher. Cahén, a brilliant painter and Maclean’s contributor, had died in a car accident, leaving the art for two texts unfinished. Could Sneyd complete the job in Cahén’s style? The job transformed him—Sneyd adopted Cahén’s loose drawing line and discovered Dr. Ph. Martin’s watercolours, which Cahén used in his work. With this style of illustration, Sneyd approached an art director at the Playboy offices in Chicago. A Playboy fan, Sneyd saw it more as a lucrative gig—“the up and coming magazine”—than as an excuse to draw ribald pictures. “Many artists are driven by a need to create,” says his son Michael, CEO of a Toronto-based development firm. “His art was a way to support his family.” Sneyd offered himself as an illustrator; the art director saw him as a budding cartoonist. “That wasn’t my cup of tea,” he says. “Then he told me what they paid for cartoons and I changed my taste in tea.”

Soon Hefner was writing memos: mostly he wanted Sneyd to avoid cartoon clichés. “In second-rate magazines, the very same gag may appear, but it is ordinarily overstated—in the characters, in their costumes and setting and in the situation itself,” Hefner wrote. “It is the difference between sophisticated comedy and burlesque.” He proved an exacting editor: “On the redhead,” he once complained, “the placement of the dot for the navel seems a bit off in location, considering the location of the crotch—it seems as though the navel ought to be a bit further over to the left.” (Sneyd has self-published a book, Unpublished Sneyd, showcasing his favourite cast-offs.) “The girl is delightful,” Hefner writes elsewhere. “I wouldn’t mind if she were just a bit fuller in the bosom.”

Such made-to-order women achieve an impossible perfection, as Lynn Johnston, the For Better or For Worse cartoonist and a good friend of Sneyd’s, observes in an introduction to The Art of Doug Sneyd: “Doug’s girls are 11 out of 10.” But it’s that sense of fantasy that keeps Sneyd’s girlfriend contented. “I’m competing with fictional women, so I don’t feel threatened,” Hutson says of his pen-and-ink harem. This brings us to how Sneyd managed to introduce Hefner, a long-time boss he barely knows, to a new “squeeze,” in Sneyd parlance.

For years, Sneyd has attended comic conventions to sell books, and often scribbles a portrait of the buyer’s girlfriend in the flyleaf. On one occasion in 2010, at the Toronto Reference Library, Sneyd couldn’t help but marvel at his model: “I said, ‘My God you’re a 10.’ And she said, ‘Thank you very much.’ She was absolutely Hollywood perfect, and so Sneyd phoned Playboy about Shera Bechard. Weeks later, she called: “I’m going to be Miss November,” she told him. Late last year, Sneyd got a Christmas card from the Playboy Mansion: it was Hef, recently jilted by Crystal Harris, wearing a tux and flanked by two new girlfriends. One was Bechard. What does Hefner think of this kismet—a man he’s known, remotely, for nearly 50 years, sending him a woman from Kapuskasing? “Refresh my memory,” Hefner, not quite aware of the story, asks a reporter. He listens to the Sneyd account and is bemused. “The relationship became a personal one,” he says with the faintest hint of bashfulness. “And she is my No. 1 girlfriend.”