How Monty Python’s Michael Palin became fascinated with the doomed Franklin ship

Michael Palin on the Erebus shipwreck resonates around the world: ‘A dramatic, catastrophic failure is always a great story’

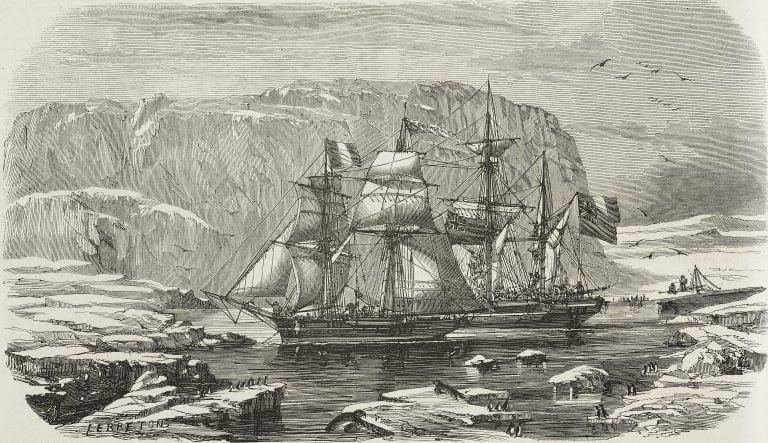

The Erebus and Terror ships from John Franklin’s expedition, in the bay where they spent the winter of 1845-1846, illustration by Le Breton from L’Illustration, Journal Universel, No 529, Volume XXI, April 16, 1853. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Share

In the summer of 2014, after wrapping up the latest revival of the Monty Python comedy troupe, a 10-day stage performance in London, Michael Palin was looking for a new project. He had turned his boyhood love of geography and exploration into a post-Python career as a popular travel writer, but now Palin wanted—in Python jargon—“something completely different,” preferably having to do with Joseph Hooker, the eminent Victorian botanist and traveller. That’s why, two weeks after he had “sold the last dead parrot and sang the last lumberjack song,” Palin was electrified by news of the discovery of the wreck of HMS Erebus, the command ship in John Franklin’s doomed 1845 Arctic expedition. Already aware—because Hooker had been aboard—of Erebus’s other polar expedition, its highly successful 18-month exploration of Antarctica, Palin dove into naval records, newspaper accounts and private correspondence. The eventual result, Erebus, is extraordinary. Part biography of a ship, from its birth two centuries ago to its contemporary resurrection, and part study in courageous folly, Erebus also thoroughly sifts through the many varied and often contradictory theories about what happened to the 129 men aboard Franklin’s two ships.

Q: Why the focus on Erebus? I always think of Franklin’s ships as a pair, and Terror also accompanied Erebus to the Antarctic.

A: It’s just the way I was led to the story. I came to it from studying Hooker, and he led me to Erebus, where he was assistant surgeon. Something about Erebus and its name—you know, the son of Chaos—caught my imagination. And it was always the command vessel of the two, with the expedition leader on board, whether [James Clark] Ross or Franklin, and the slightly bigger, slightly more modern one. What I wanted to do was, rather than talk about just the expeditions, to make the book into the life history of a ship. Also, at the time it was the only one that was discovered. Terror wasn’t located until 2016, but it is a vital part of the story.

Q: Why do you think the story resonates so much? In Canada, understandably, but outside this country too?

A: A dramatic, catastrophic failure is always a great story. People are fascinated because we’re all a bit scared and nervous about being on this earth. We like to see what can go wrong, so it won’t happen to us. The disappearance too—I think that’s something which fascinates people, not just that they were killed and that’s the end of it. No one knew what happened or where did they go, and the ice and the cold—all the sort of elements that threaten us, put together.

Q: It’s a British—and Canadian thing too, I think—that heroic failure is so much more moving.

A: It is, I’m afraid, more than success, which was the story of the first expedition, the one that nobody has heard about. We do like a failure. I think that’s not a bad thing, because if you don’t admit your failures and just repaint them for history as triumphs—as might happen in certain countries which are slightly more triumph-focused—that’s a bad thing. The fascination for me in writing the book was just how the British public dealt with the news over the years. What I saw was three stages: first, the vociferous denial when the cannibalism evidence was first cited that any British sailor would ever eat another British sailor—oh, that’s sort of a throwback to a Python sketch where we had sailors stuck in a lifeboat, rejecting suggested victims as too lean or not kosher, with one who kept piping up, “eat me, eat me.” Then the public response moved from denial to acceptance but seeing it as divine providence—they were up against nature at its most brutal and they died in a…well, in a grave way. Final stage was acceptance: they’d blown it.

Q: Erebus was a strangely modern ship by the time it went to the Arctic. It has a steam-driven propeller, a steam-heating system, even a library with bestselling novels. Which actually put it on the cusp of old and new: an able seaman could check out a copy of A Christmas Carol and he could still be flogged.

A: That’s right, and I suppose it sets you up for your own choice, really: do I want to get flogged or read Dickens? Maybe reading will take my mind off naughty thoughts. Franklin was quite a schoolmaster in a way. He tried to improve the minds of his sailors.

Q: As often happens, wartime research and expenditure pay some peacetime dividends. The Royal Navy built all these heavily reinforced little “bomb boats” with their meant-to-terrify names to carry very heavy mortars for firing over coastal defence walls. Then, in peacetime, when their budget was slashed and they were looking around for what might be best for surviving pack ice, the Admiralty’s eye falls upon Erebus and Terror.

A: Exactly. That was a marvellous sort of repositioning of ship assets, wasn’t it? But the ships themselves were quite small, really only 30 metres long. And purely sailing ships, until Erebus was retrofitted. The hulls were strong and the decks had diagonal planking to deal with recoil from the mortars, but still they don’t seem like the sort of ship you’d want in polar regions, especially in the Southern Ocean, where the gales come bombarding you all the time even before you get to Antarctica. So it was actually a great gamble that these little ships could cope. They were only 370-odd tonnes, which might not mean anything until you learn Nelson’s flagship, Victory, was 2,100 tonnes. I’m always trying to work out a size comparison. You know those little regional jets the airlines use now, kind of 120-seaters? Those are Erebus and Terror; Victory is an Airbus.

Q: One of the more striking individuals in the book is the surgeon Robert McCormick, Hooker’s boss on the Antarctic voyage. A self-described “lover of the feathered race,” he seemed to spend most of his spare time slaughtering birds in job lots. Is he your favourite character?

A: He’s pretty much up there as a wacky figure. But I quite like Sgt. William Cunningham, in command of the Royal Marines on Terror, who kept a diary where he talked about bullocks being slaughtered and so on. And he had one wonderful phrase—after the men had gone ashore and got absolutely arseholed, he described it as “a lot of men disordered in the attic,” which I think is a great description of being drunk. And there’s [Francis] Crozier, who I quite liked because there was a lot of self-doubt there, quite an interesting psychological character. But yes, McCormick. He’s in the talk I give on the book. I read a section about him killing birds and then another one, and then another one… You have to consider they were going to places no one had ever been before. They have to bring back evidence of what they find there from the natural world. They didn’t have a camera. They never had the weather to stop and do nice, neat, gentle drawings. So it was skulls and pelts and all that sort of thing.

Q: So, to the fatal journey, where again you walk a fine line. You mine the personal letters and journals from the southern voyage, which reveal the emotional toll exacted, and the letters Franklin’s men sent via the last accompanying supply vessel when it turned back to Britain. But you let Erebus and Terror sail on into silence. You don’t try to imagine your way into their final days. Why is that?

A: As long as there’s a letter or some document to back up my theories, I’ll do it. I go on at some length about the last letters back from Greenland, especially Franklin’s 14-page one to his wife, with all his worries, whether he’s good enough to do the job, whether Crozier is his friend or not. I wanted to push those so people would realize the explorers are going into the Northwest Passage with those feelings unresolved. I didn’t want to go any further than that because then you get to fiction and I didn’t want the book to be that.

Q: A lot of writers would feel obliged to say, “We can only imagine what happened as the food ran low…”

A: Oh yeah exactly. I deliberately wanted to avoid saying, “We can only imagine,” or “It must have been a grim day, probably his foot was hurting,” and so on. No, no, although I do swear there’s a story in the monkey [Lady Franklin gave the expedition]. He probably got away, scampered across the ice howling until a polar bear ate him.

Q: They remained stuck in the ice for two years, in good order as witnessed by the “All well” note left in a cairn at Victory Point. But the third winter was bad: Franklin, eight other officers and 14 crewmen had died, and in April, the remaining men head south after updating the “All well” note to record the deaths and that they were abandoning ship. Then what?

A: Hard to say. They may not have gone far as a group—there’s a lot of debate whether any of them go back to repossess the ships. And, of course, about what had happened to them. There are so many deaths between “All well” and the update to that note. Scurvy or something like that?

Q: The deaths actually make a case for the botulism-from-tinned-food theory, because of the disproportionate death toll on officers, who would have had more tinned delicacies in their private stores. As for some men returning to the ships, the Inuit said they did, and the Inuit have been right about everything.

A: That’s right, they have, so the men probably soon split up and some came back, probably to one of the ships, probably Erebus. There’s also the whole interesting area of not just what killed them—scurvy, lead poisoning, consumption they brought with them, some combination—but whether they had actually gone slightly crazy after all that time or from their illnesses. What were they thinking when they stormed off south? That was a huge distance they planned to cover while pulling a 250-kg sled with a boat on top. They were never going to get far. And why did they abandon 600 cans of food? Did someone decide the food was bad? All this is why this is such a good story, so frighteningly irresistible.

Q: You followed in Erebus’s wake all over the world—Tasmania, Rio, the Falklands, the Orkneys—but last year, when you were finally going to catch up to it in the Arctic, you couldn’t get to the wreck because of the ice. I imagine this last-mile irony has been weighing on your mind?

A: Oh, absolutely. I’ve been thinking about that ever since. For some reason—I mean global warming mostly, but also being on a big Russian icebreaker—I assumed that we can now sail wherever we want. But you really can’t. The rising temperatures mean there is actually more floating ice than there once was. Someday, I’ll be back, and I’ll see my ship.