Inside Queen Elizabeth’s bedroom

Book review: ‘The Queen’s bed: An intimate history of Elizabeth’s court’, by Anna Whitelock

Share

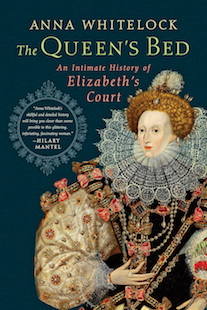

THE QUEEN’S BED: AN INTIMATE HISTORY OF ELIZABETH’S COURT

By Anna Whitelock

Was she or wasn’t she? To phrase this otherwise: Was the so-called Virgin Queen deserving of her title?

Anna Whitelock’s new history of Queen Elizabeth I begins in the royal bedchambers. It is 1558 and young Elizabeth—daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn—has just acceded to the English throne and restored Protestantism to the land. It is then and there that “for the first of many times, Elizabeth’s chastity became a subject of gossip.” It would remain so forever more: a point of continental obsession, ruminated over by the likes of French kings and Italian popes.

The Queen’s Bed offers a sweeping history of Queen Elizabeth’s rule, focusing especially on the politics of Her Majesty’s sex: the times at which Elizabeth’s body became a matter for the body politic. We cheer the queen on in her 20s—as she resists her privy council’s fevered attempts to arrange a royal marriage. Later, we peek into Elizabeth’s (alleged? consummated?) love affairs. And we delight in her haphazard efforts to court a husband. A particularly readable episode describes when the almost-40-year-old queen is being pushed to marry a young French duke in 1571. “It was hardly an ideal pairing,” Whitelock rues. “Anjou was 18 years younger than Elizabeth…and a blatant transvestite who regularly appeared at court balls in elaborate female dress.” (The duke also viewed Elizabeth as a “heretical bastard.”) In later chapters, we see Elizabeth through menopause—and wince at her desperate attempts to hide her age: with ointments and extracts, garish (and, it turns out, poisonous) lip colours and egg-white face glazes.

This book is also a rich history of larger 16th-century events: theological contests between Catholics and Protestants; the rise and fall (and beheading) of Mary, Queen of Scots; pitched battles with Spain. In fact, the book may have benefited if a smidge of this broader narrative had been shaved off so that it focused more narrowly on the queen’s bed itself. (Or, rather, beds. The queen had many. Her favourite, layered in gold and silver lace and adorned with ostrich features, travelled with her when she roamed from palace to palace.) Nevertheless, it is the vibrant Queen Elizabeth who carries the day. We get to know this most unusual monarch through more than 60 short chapters, all gorgeously detailed and with such enticing titles as “Not a morning person,” “Toothache,” “Amorous potions” and “Privy matters.”

This book is also a rich history of larger 16th-century events: theological contests between Catholics and Protestants; the rise and fall (and beheading) of Mary, Queen of Scots; pitched battles with Spain. In fact, the book may have benefited if a smidge of this broader narrative had been shaved off so that it focused more narrowly on the queen’s bed itself. (Or, rather, beds. The queen had many. Her favourite, layered in gold and silver lace and adorned with ostrich features, travelled with her when she roamed from palace to palace.) Nevertheless, it is the vibrant Queen Elizabeth who carries the day. We get to know this most unusual monarch through more than 60 short chapters, all gorgeously detailed and with such enticing titles as “Not a morning person,” “Toothache,” “Amorous potions” and “Privy matters.”

At the book’s end (the queen’s ladies-in-waiting are preventing her corpse from being disembowelled and embalmed, in accordance with her dying wishes), readers may find themselves reflecting on our present-day preoccupation with the recently demonstrated fecundity of duchess Catherine.