Loretta Lynn for the post-Occupy age

With its class-conscious crossover stars, country is picking up where hip hop left off

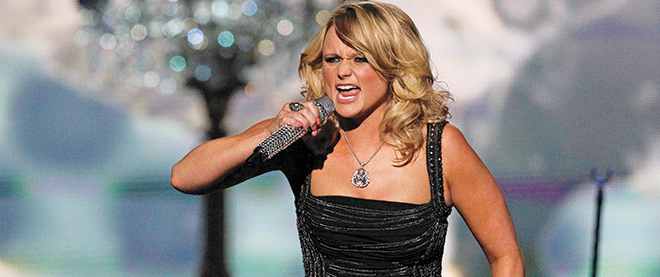

Mario Anzuoni/Reuters

Share

Austerity is not the most fruitful territory for songwriters looking to craft a hit. As a rule, pop music is either aspirational or escapist, or some intoxicating blend of the two; pinching pennies and paying rent don’t exactly fit. But in the post-Occupy age, with unemployment and income inequality at the top of people’s minds, it seems the 99 per cent may have developed an appetite for class-conscious messages to go with their iPod-rocking hooks. The most obvious example is Lorde’s anti-bling hit, Royals. But the real seeds of revolution are being planted in a far more unlikely place. Though it’s viewed as a bastion of conservatism, country music is undergoing a transformation—due in no small part to an army of unabashedly brazen women who are working to change the reputation of the genre, and that of its audience.

Leading the charge is Kacey Musgraves. Nominated in the high-profile best new artist category at this year’s Grammy Awards, held Jan. 25, the 24-year-old troubadour seems engineered for crossover success. She grew up listening to alt-rock, did a stint on the reality-TV show Nashville Star, and performs music that’s openly progressive—both sonically and ideologically. Much has been made of Musgraves’s single Follow Your Arrow, which casually alludes to homosexuality, but the meatiest content of her songs lies in her descriptions of the psychic malaise that can paralyze rural working-class folks. On Merry-Go-Round, from her debut album, Same Trailer Different Park, she’s frank: We get bored, so we get married / Just like dust, we settle in this town.

“I don’t like it when people try to pretty up a situation,” she said in an interview last August. “Yeah, it’s kind of a tough economy and people may want to get their minds off that, but they also want to feel like they’re being related to. Even if it’s kind of bleak or depressing, maybe they take comfort in the fact they’re not alone.”

That desire to articulate the reality of average folks in crappy circumstances is something country music shares with hip hop. The latter has traditionally been a stronghold for class analysis. As it’s evolved and infiltrated middle-of-the-road pop music, though, that mode has been diluted. Country may have a complicated legacy to work through, but it’s not bound up in the same thorny history of slavery and racial disparity. Its class ethos is less byzantine, its aspirational aspects simpler to express.

Few artists explore this to better effect than Brandy Clark. Born in a logging town in Washington state and based in Nashville, Clark is an outsider in an insular community: an out lesbian in country music, a transplant from the birthplace of grunge whose tunes top Bible Belt charts. Her debut album, 12 Stories, racked up accolades. Her most significant achievements, however, have been at the hands—or mouths, really—of others. She’s written songs for Keith Urban and Sheryl Crow, as well as Musgraves, and is nominated for a best country song Grammy for her work on Mama’s Broken Heart, a massive hit for the singer Miranda Lambert.

“I got in my head that my goal as a songwriter was to write songs for people who didn’t write songs,” Clark told one interviewer; she’s speaking, she’s said, for “the moms who are driving their daughters to see Taylor Swift.” Like Swift, the biggest pop-country crossover success story of our time, Clark has an expansive sense of her audience. In the first track on her superb album, she cuts to the chase: We live in trailers and apartments, too / From California to Kalamazoo. That “we” is a hardscrabble group, limited by financial means but not geography or world view. Her characters play the Lotto and pray; they also pop pills and smoke pot.

In Clark’s work, you can hear echoes of the wry, unflinching anthems of Dolly Parton and Loretta Lynn. But the female voices who blazed a trail in traditional country music haven’t always been able to find a place within new country. With its staunch conservatism and evangelical underpinnings, the genre has more space for tawdry mudflap girls than outspoken feminists. This new breed of badass is a welcome development.