Man enough to laugh at cancer

Inspired by ‘Movember,’ a number of other fundraisers aimed at men take a less serious approach

Share

A couple of months ago, men were sprouting moustaches for “Movember,” a month-long campaign that raised over $21 million—nearly triple last year’s total—for Prostate Cancer Canada. (Liberal Mark Holland, who tried but failed to grow a handlebar, was one of more than 80 MPs who donated the space above their upper lip through November.) Partly inspired by Movember’s success, the Canadian Testicular Cancer Association (TCTCA) has claimed a month of its own. During January, or rather MANuary, the TCTCA aims to teach men “how to have the balls” to talk about testicular cancer.

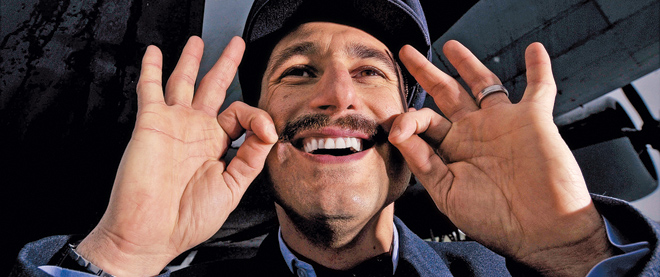

The first-ever MANuary doesn’t encourage anyone to grow more hair—quite the opposite, in fact. In one MANuary fundraising event ripped straight from The 40-Year-Old Virgin, “volunteers will get their backs waxed on stage,” says actor-comedian Peter Laneas, a testicular cancer survivor and spokesperson for the TCTCA. “Nothing brings people together better than public humiliation,” he jokes.

Cheeky marketing has more commonly been used by breast cancer groups: foundations like Feel Your Boobies and Save the ta-tas grab attention—and fundraising dollars—with fun, sexy messaging. Now humour is doing the same for cancers that typically affect men. Prostate cancer is as prevalent as breast cancer, says Adam Garone, CEO and co-founder of the Movember Foundation, “but guys don’t like talking about their health, especially below the waist.” The first Movember campaign was held in Australia in 2004; in 2010, close to half a million people took part globally. “When we survey the guys on why they participate,” says Garone, “the number one reason is because it’s fun.”

Mark Daku, who’s working toward a Ph.D. in political science at McGill University, thought Movember was a “cool idea,” so in 2009, he started something similar—”Decemburns,” which encourages men to grow sideburns to raise money for the Stephen Lewis Foundation, and to raise awareness of HIV/AIDS in Africa and its impact on women. In its first year, with fewer than 10 participants, Daku’s effort raised more than $4,000, and “we’re on par to do better” in 2010. (Perhaps feeling left out, bloggers at Feministing launched “Decembrow,” encouraging women to grow a unibrow for charity.)

These campaigns have earned plenty of press, but humour can occasionally backfire. Critics argue that they make light of conditions and diseases that, in all too many cases, are deadly serious. Laneas admits that hitting the right note can be tricky. “You have to gauge the audience,” he says.

But if humour helps more young men feel comfortable talking about testicular cancer—the most common form of cancer among men between the ages of 15 and 29—it’s worth it, he says. Testicular cancer has a 97 per cent cure rate, and detection is crucial, but too many men avoid having potential symptoms checked out: after all, the thought of losing a testicle to cancer can be terrifying. “Testicles are a representation of manhood,” Laneas says. “When I talk to young men, the most common question I get asked is, ‘How am I going to get a girlfriend?’ It’s important to take away that taboo.”