BlackBerry director Matt Johnson on creating the buzziest new film in Canadian cinema

To tell the story of a fallen tech giant, he channelled his inner Dolly Parton

Share

BlackBerry tells the story of Canadian tech founders Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie, an opposites attract duo who turned a tech innovation (the world’s first smartphone) into a billion-dollar phenomenon—and then watched it flame out in equally spectacular fashion. The movie premiered at the Berlin Film Festival last month, and it’s already being hailed as Canada’s answer to The Social Network, a comparison director Matt Johnson takes as a compliment (though he believes the Canadian movie industry needs to stop trying to imitate our southern neighbours). BlackBerry is Johnson’s third feature film—a significant departure from earlier indie fare, but also a deeply personal project. Here he talks about why Canadian filmmakers should channel their inner Balsillie and life lessons from one of his cinematic north stars: Dolly Parton.

As a director, you’re known for experimental indie work, but BlackBerry is more of a classic biopic. Why was this iconic Canadian tech story the right project for you?

I think precisely because of what you’re saying. On its face, the BlackBerry story seems a little dry. People go, “Why would I ever watch a movie about a dead cellphone that I never cared about when it existed?” That skepticism became a bridge toward my more inaccessible style of filmmaking. I’ve always struggled trying to make films for a larger audience because my work is so personal. This film is also ridiculously personal, but that part of it is combined with this broader, real-world story.

You say your style is inaccessible, but BlackBerry doesn’t feel that way.

My previous films are these slightly arcane, hardcore fake documentaries where the audience has to buy into the format to enjoy it. The intention with BlackBerry is to make it seem like you’re in the room with these guys, which is hard to approximate with more traditional camerawork. In some ways, it’s the anti-Spielberg or anti-Fincher or anti-Kubrick approach, where it seems like it’s happening by chance and the footage has been discovered. I like making films that almost disguise themselves as being really low budget, really low effort.

I’m reminded of that Dolly Parton quote: “It takes a lot of money to look this cheap.”

That quote has been a central philosophy for me since I was 16 years old. Dolly is a genius, and you can see her influence in artists who were inspired by her, going as far as Kurt Cobain, Andy Warhol, where the brilliance just seems like a fluke but then you scratch the surface a bit, and you realize, “Oh my God…”

You were in your 20s when BlackBerry was in its heyday. Did you own one?

Before we started shooting, I had never even touched a BlackBerry. I did have a good friend who always used to make jokes about BlackBerry’s messaging service that I never really understood. Not to say I was a total luddite, but that entire generation of tech totally missed me.

So what do you mean when you say the story is very personal?

When I was first reading about the story of BlackBerry, what struck me was how much their journey was like my experience making my first film. I also had some success and then watched all of my personal relationships change overnight. I wrote the script with my producing partner, Matt Miller. We used a book called Losing the Signal: The Untold Story Behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry, written by two Canadian journalists, as our backbone, which hinted at the tenser aspects of the relationship.

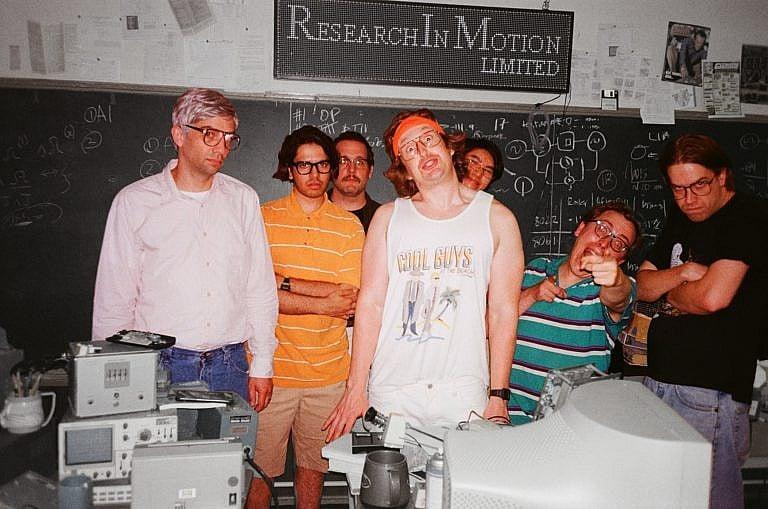

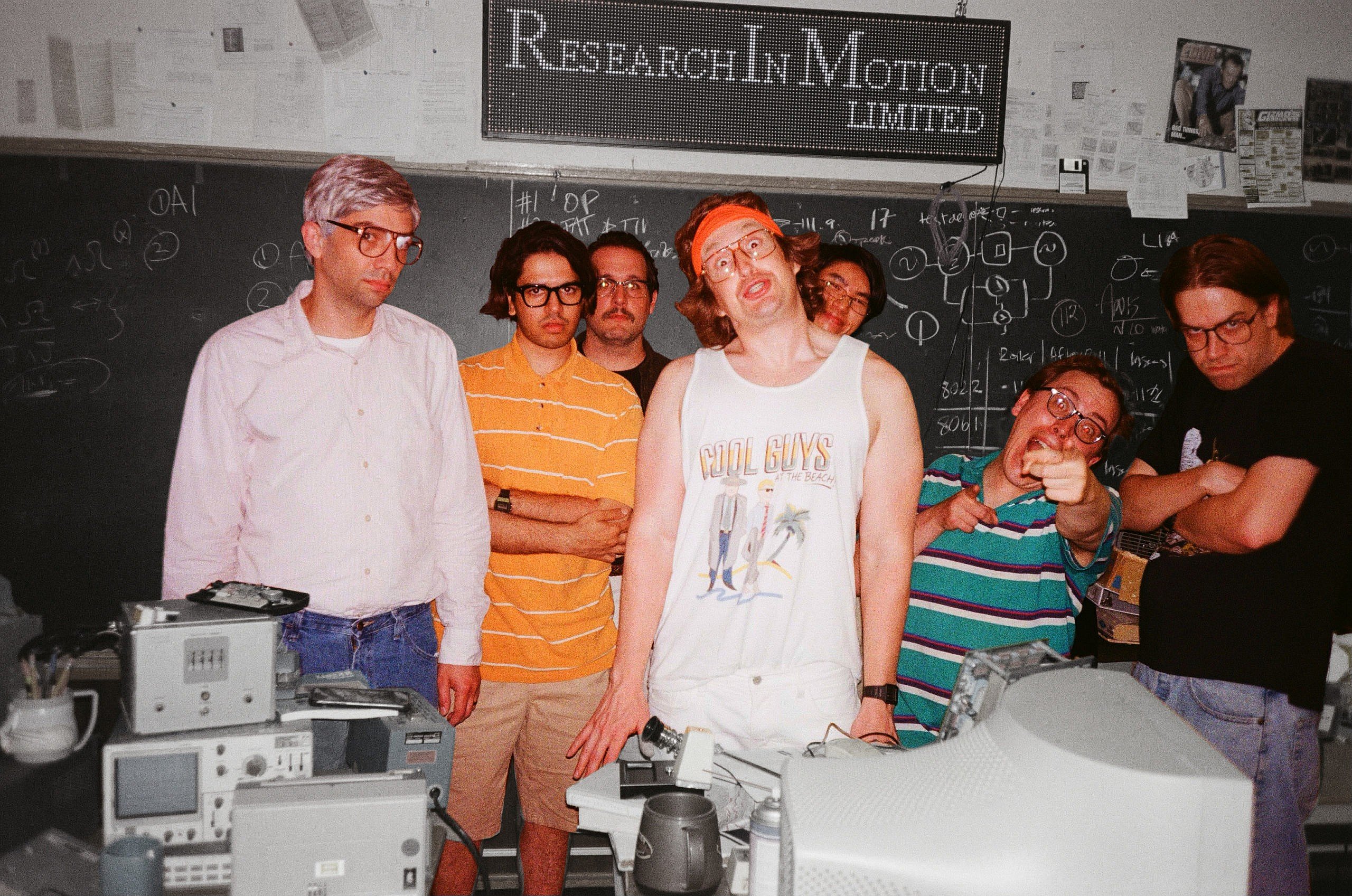

To fill in the details, we spoke to some of the young engineers who worked for the company in the early days—one guy had kept journals and photographs from that time, which was amazing. Then Matt and I transposed many of our own experiences on top of the BlackBerry story. Ultimately, we wanted to make a movie that was about work, what it means to go to work, the meaning you get from it, the justification for working all night on projects that may or may not deliver anything, that lust for power, the need to create things solely to enlarge your status. These are all the dark sides of my own personality dancing together on screen. When you see Mike, Jim and co-founder Doug Fregin, you’re essentially watching me and my life split into three people.

I can see you in Mike, the exacting creative genius, and Doug, the loyal, lovable manchild. But what about Jim Balsillie?

I’ll put it this way: if you were to ask any of my closest friends which of the three was the most like me, they’d all say Jim. In my opinion, Jim Balsillie is portrayed in this movie as being very kind. At no point is he sadistic. Deep down, all he wants is to be the best. Of course, he’s totally misguided. Without a Mike or a Doug, the Jim personality type is heartless. I remember one actor described Jim as a character who consumes without tasting, which I thought was really good. He wants to win only for the sake of winning, so when I say I’m like him, that’s only a piece of me. The Mike in me and the Doug in me also want to win for different reasons.

In the movie, Jim has one mode of communication: yelling. I can’t imagine that’s you on set.

No, no. I’ve never yelled at anyone in my life. It’s more Jim’s attitude: if it’s going to benefit their company, anything is justified. That’s certainly how I feel as a filmmaker, which is not very Canadian. One of Jim’s central personality traits is that he almost has an Americanness to him.

What means are justified by this movie?

I will give you an example from my last movie, Operation Avalanche, which was supposed to be set in NASA in the 1960s. We couldn’t recreate it because we didn’t have enough money, so we posed as film students making a documentary. We flew to NASA in Texas, shot our whole movie illegally and then released it. We did about 100 versions of that on BlackBerry. When you’re watching the characters drive into the offices and park in the parking lot, that’s really where it all happened.

You cast Jay Baruchel, who most audiences know as a lovable stoner, as Mike Lazaridis. Was that an obvious call?

Jay was an early partner on the film. I knew him because my editor, Curt Lobb, also edited his feature, Random Acts of Violence, so we met as friends. Very quickly, I saw that the real Jay was quite different from the one I had seen in movies. He’s a perfectionist in the best way. He has really high standards, and he seemed to understand the at-all-costs, this-must-be-right attitude that Mike Lazaridis had.

MORE: Q&A: BlackBerry’s Jay Baruchel loves movies, hockey, weed and his now-obsolete phone

BlackBerry premiered to amazing reviews at the Berlin Film Festival in February. People are already calling it Canada’s version of The Social Network. Is that a compliment?

Absolutely, I see that as a huge compliment. The Social Network was revolutionary. It came out in 2010, and people are still talking about it. The comparisons were inevitable, and we leaned into that with the script. I tried to steal as much of that Sorkin style as we could.

You wore a Jays T-shirt to the BlackBerry press event in Berlin. Was that on purpose or did they lose your luggage?

No, no, that’s one of my favourite shirts. I’m very proud to be Canadian—I would say stupidly so. When I was growing up, my dad said, “This is the greatest country in the world. You’re lucky to be here.” I still believe that. I will say that Canada is a joke as a filmmaking country. When people find out BlackBerry is Canadian, they’re shocked, in the same way that they’re shocked that BlackBerry is a Canadian product. There’s a good reason for that. Part of it is that we’re extremely modest—we’re not like Jim Balsillie.

Best advice for aspiring Canadian filmmakers?

I would encourage people to find their own style—especially a visual style—rather than trying to copy the Americans. When that happens, we end up with this sort of ersatz, uncanny valley version of American-style filmmaking, which needs budgets four, five, six times of what we’re dealing with. There’s a saying amongst filmmakers that something seems “Canadian” when there’s just something slightly wrong, like looking at a clone of your mother.

Given the early buzz, what are your hopes for the next few months?

I really have no idea. For me, it still feels like a very small movie about me and my friends, but I guess the Jim Balsillie in me is hoping it plays everywhere.

That Jim Balsillie is already walking the red carpet at the Oscars in 2024!

Right, and then the Canadian in me is saying, “Well, don’t get your hopes up.”