How ‘The Shape of Water’ became the movie of the moment

In an Oscars ceremony that capped off Hollywood’s annus horribilis, it’s no great shock that Best Picture went to a comfortable, inoffensive morality tale

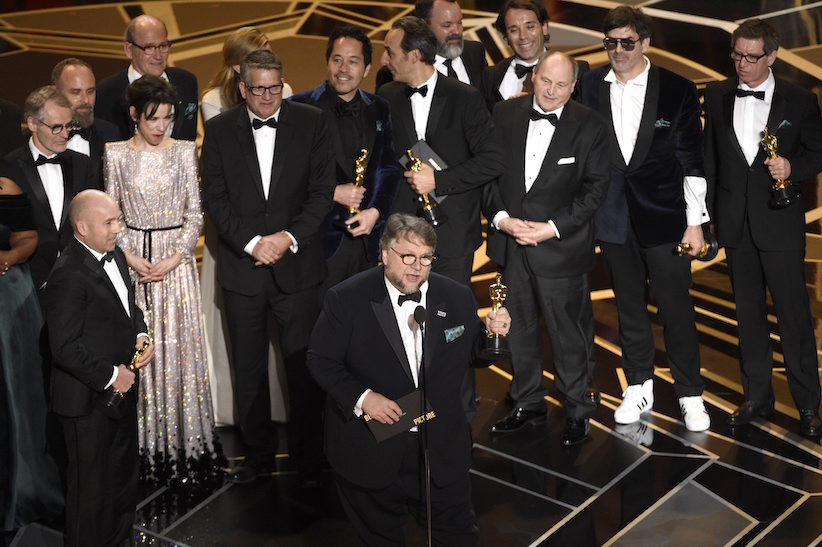

Guillermo del Toro and the cast and crew of “The Shape of Water” accept the award for best picture at the Oscars on Sunday, March 4, 2018, at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles. (Photo by Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP)

Share

When not preoccupied with sexually assaulting and harassing actresses, Harvey Weinstein lived and breathed for winning Oscar campaigns, seizing both women and awards as his divine right. Over the past year, as this real-life monster surfaced from a black lagoon of secrets and lies, it was like watching an X-rated horror movie, the story of a sexual predator more preposterous than any Marvel villain. So on Sunday night, as Oscar put on a brave face to celebrate its 90th anniversary, everyone was in the mood for salvation. And for once, the universe unfolded as it should—or, at least, as it was predicted.

After its annus horribilis, Hollywood found safe haven in an attractive but innocuous Gothic romance about a mute cleaning woman in a Cold War lab who falls for the most benign monster imaginable—an amphibian with a taste for hard-boiled eggs who makes himself at home in a bath, rather than a bathrobe, an eroticized merman without a predatory bone in his scaly body. As host Jimmy Kimmel joked, “this year men screwed up so badly, women started dating fish.”

In the most politically messaged Oscar ceremony in history, The Shape of Water, which led the field with 13 nominations, won Best Picture and Best Director. In honouring Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro—who now lives and works in Toronto, where the movie was shot—the Academy also gained an eloquent goodwill ambassador for diversity and tolerance. “I am an immigrant,” del Toro proclaimed from the podium. “And in the last 25 years I’ve been living in a country all of our own. Because the greatest thing that art does and that our industry does is to erase the lines in the sand. We should continue doing that when the world tells us to make them deeper.” Essentially offering himself up as a director without borders, del Toro has, in fact, made a truly international film—directed by a Mexican, filmed in Canada, starring a British actress as a Baltimore janitor smitten with an Amazon river god.

So why did this odd fable become the movie of the moment? The battle for Best Picture came down to a duel between The Shape of Water and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, two tales of embattled heroines that could not be more different. The former is a retro beauty-and-the-beast romance, the latter a caustic tale of maternal rage in a contemporary Southern town—though both are essentially melodramas.

READ MORE: The problem with Shape of Water and “woke cinema”

Three Billboards, voted the most popular movie at the Toronto International Film Festival, initially looked like the favourite. Though written nine years earlier by British director Martin McDonagh, its story of sexual assault and racism takes uncanny aim at the American zeitgeist. As expected, Frances McDormand won Best Actress as its incendiary heroine, who declares war on the police in a Southern town for persecuting Black folks while failing to solve the rape and murder of her teenage daughter. And on Sunday night, McDormand still appeared to be in character as that loopy, anarcho-feminist firebrand when she marched up to the Oscar podium and rallied the women in the room. Sam Rockwell, meanwhile, rightly won Supporting Actor for navigating his high-wire character arc as a cop who mutates from lazy bigot to Southern-fried saviour.

The movie itself, however, became divisive. It triggered a stern backlash from the left as critics attacked it for being too white, and for relegating Black people to token roles, while some dismissed its satire as a smug caricature of redneck America by a smarty-pants English filmmaker. Yet what allowed Three Billboards to become so controversial, aside from the script’s bursts of racist profanity, was its moral ambiguity, which persisted right up to its final frames. Every character was etched with imperfection. Its heroine manages to be loveable in spite of being aggressively unlikable. Rockwell’s character is a dolt who blunders his way to the most unlikely redemption. And the nicest, smartest, most loveable guy in the movie, the police chief played by Woody Harrelson, blithely checks out by playing a lethally cruel trick on his wife, his family and his horse, not to mention the audience. This is a movie that took wild risks and was wonderfully unpredictable from one shot to the next.

The Shape of Water, on the other hand, is a scrupulously inoffensive morality tale. While its trappings may seem unorthodox—mute janitor gets turned on by caged amphibian, then sets it free—its drama of pure good versus pure evil could not be more conventional. Del Toro has concocted an adult fairy tale, elevating Gothic horror from the B-movie gutter, and detoxifying it with the soothing bath salts of intersectional politics. He dutifully name-checks minorities—the heroine with a disability, her closeted gay neighbour, her feisty Black female colleague—while upping the ante on gender fluidity with a heavenly interspecies romance. Who could ask for anything more?

READ MORE: The Oscar machine Weinstein built ticks along, with only a few dings

Yet while we think of Hollywood romance as a conventional genre, it can be hard to find an example of it outside the realm of the romcom these days. Among this year’s nine Best Picture nominees, there was only one other flat-out love story, the bucolic gay interlude of Call Me By Your Name, and it’s more of a coming-of-age summer fling than a fable of undying love. What may have made The Shape of Water most palatable to Oscar voters is the fact that it’s a Serious Romance—and its ultimate love object is Hollywood itself. Like last year’s almost-winner, La La Land, it holds an adoring mirror up to the movies and their gilded history. Del Toro’s heroine lives above a movie theatre (actually a mix of Toronto’s Massey Hall and Elgin Theatre), and from the script to the production design, the film unfolds as an homage to vintage cinema.

The Shape of Water may have originated from del Toro’s love for monsters and Gothic horror, but he’s the first to admit it plays more like a classic musical. In fact, it even has a fantasy sequence of its two lovers dancing in an ethereal ballroom, just like La La Land. This is a movie that landed right in the Academy’s coziest comfort zone: a gorgeous period film that provided a dignified escape from the horrors of the world around us.

Compare that to Jordan Peele’s Get Out, a truly scary horror film that some Academy members admitted they refused to see because they considered its genre not of Oscar pedigree. (Peele’s consolation prize was Best Original Screenplay, which he utterly deserved for his fiercely original script.) Among the acting winners, warriors were rewarded, from Gary Oldman as Winston Churchill in The Darkest Hour to Allison Janney as an abusive mother in I, Tonya. And the Academy had no problem recognizing the pugnacious brilliance of both McDormand and Rockwell in Three Billboards.

But as Best Picture candidates, Three Billboards, Get Out and I, Tonya (which wasn’t even nominated) were all handicapped by their satirical bite, and their mongrel mix of drama and comedy. One must never forget that the name of the game at the Oscars is Triumph of the Human Spirit, which is no joke—with motion pictures, as with figure skating, there are marks given for a certain class of presentation.

Not so long ago at the Academy Awards, it was strictly verboten—downright undignified—to make political speeches. But this year it would have been unfashionable not to make them. Even some of the presenters framed their words with scripted manifestos, cheering on #MeToo, #TimesUp and gun control. But Hollywood’s most cherished slogan has not changed: Dream! This year, the Dream World of the movies and the cause of undocumented immigrant children known as Dreamers dovetailed with fateful precision. And as the awards reached their climax, Oscar found its avuncular poster boy in the rumpled Guillermo del Toro, as he framed his own success as a Hollywood fable.

“Growing up in Mexico as a kid, I thought this could never happen,” he said. “I was a big admirer of foreign films.” Then, deftly upending our notion of “foreign film,” he cited E.T. and Hollywood directors like Douglas Sirk and Frank Capra. Del Toro added that he recently ran into Steven Spielberg, who told him to remember “the legacy” if he ever got up there. But after being honoured for a picture steeped in the past, del Toro cast his eye brightly on the future: “I want to dedicate this to every young filmmaker, the youth that is showing us how things are done in every country in the world . . . Everyone who is dreaming of a parable of using drama or fantasy to tell stories of things that are real in the world today, you can do it! This is a door. Kick it open and come in.”

And with those few words, the Mexican dreamer who lives in Toronto but has shaped the world into his oyster struck a more inspiring note than the film for which he was honoured.