Inside Cannes, a film festival at a crossroads

From virtual reality to Netflix’s arrival to the emergence of women directors, Cannes finds itself in flux at 70. What comes next?

Carne y Arena. (Emmanuel Lubezki)

Share

Read Maclean’s film critic Brian D. Johnson’s dispatches from the Cannes Film Festival here.

Of all the world premieres presented at the Cannes Film Festival this week, none was more exclusive. The film, which had no stars in the cast, was only six and a half minutes long, yet it required a reservation and involved an excursion by limousine to and from a secret location on the edge of town. You watched it alone. And, strangest of all, there was no screen.

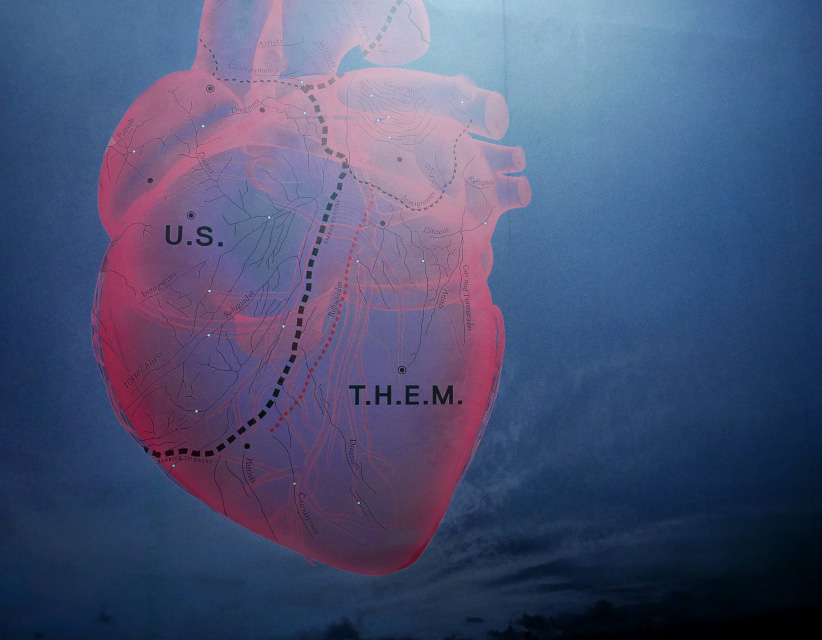

The film was Carne y Arena (Virtually Present, Physically Invisible), a virtual-reality installation created by Mexico’s Alejandro González Iñárritu, the Academy Award-winning director of Babel, Birdman and The Revenant, and shot by his frequent collaborator, Emmanuel Lubezki, who has three Oscars of his own for cinematography. Based on the true stories of refugees crossing the Mexican border to the U.S., Carne y Arena (which translates as “Meat and Sand”) takes us across a new cinematic frontier to a place where anything seems possible.

At the appointed hour, the limo left Cannes, and headed east up the coast. Our destination turned out to the Cannes municipal airport, where the “theatre” was a cavernous, empty aircraft hangar. I waited on one side of a high wall of rusting corrugated metal. It had been taken from the Arizona border, where it’s being replaced by concrete, and was made of recycled landing pads used by helicopters in the Vietnam War. I was shown into a room piled with the abandoned shoes of actual refugees, asked to remove my own shoes and socks, and at the sound of a buzzer, walked barefoot through a door into a vast space covered in sand. A couple of technicians fitted me with a VR helmet and headphones.

Then the world changed.

It was like being plunged into the heart of a movie with no frame, a 360-degree desert ringed by mountains and a twilight sky. And I was among refugees. Men, women and children running or their lives, fleeing from the U.S. border patrol. A truck roared up behind me, and guards came out with guns drawn and a fierce dog straining at a leash. A helicopter thundered into view from a blinding searchlight. As the refugees ran past me, I couldn’t touch them. I was a ghost. But because of the sensors I wore, I wasn’t entirely invisible. And when a guard aimed his gun and flashlight directly at me, screaming for me to get on the ground and put my hands in the air, it took everything to remind myself it was only a movie.

Carne y Arena is the first VR project ever programmed by Cannes. And it was one of the signs that, as the festival marked its 70th anniversary, it was clearly at a crossroads—celebrating its proud tradition of enshrining the auteur canon, while trying to embrace the future of a medium no longer confined to movie theatres. Cannes also premiered TV series for the first time in its history; David Lynch launched his Twin Peaks sequel and Jane Campion presented all six hours of Top of the Lake’s second season—though both directors possess the Cannes pedigree of having previously won the prestigious Palme D’Or prize. While Hollywood studio pictures were noticeably absent, for the first time the festival admitted two Netflix titles into competition: Okja and The Meyerowitz Stories. After Netflix refused to budge from its policy of streaming movies with no advance window of theatrical distribution, jury president Pedro Almodóvar proclaimed the two Netflix entries unworthy of the Palme even before he had seen them—a statement that ignited a controversy which generated more discussion than the movies.

While Cannes tends to incubate righteous passions about art, politics and everything in between, it all takes place in a bubble of absurd privilege. Even at the cutting edge of Iñárritu’s altruistic Carne y Arena, it was hard not to wince at the irony of riding a limo along the French Riviera to be immersed in the harrowing plight of refugees—a solo experience that could accommodate only six viewers per hour. It was an extreme example of cinema creating a safe space from which to view the horror of the human condition.

But Cannes itself operates as a kind of virtual reality, a magic kingdom that continues to elevate high art against all odds. And in 2017, that opulent bubble felt more fragile than usual. Last year’s terrorist massacre in Nice, which is just down the coast, was still a fresh memory. Columns of police vans lined La Croisette’s beachfront promenade. Men cradling machine guns guarded every access point. Screenings were delayed by line-ups for meticulous security checks. And as the stars descended on the Côte d’Azur for the anniversary ceremony, the Manchester bombing sent a chill through the festivities, prompting organizers to cancel the fireworks.

The movies offered little escape. Dire scenarios of cruelty and despair dominated the slate of 19 features in the main competition, with many stories revolving around children. They ranged from Loveless, Andrey Zvyagintsev’s austere Russian masterpiece about divorcing parents who lose track of their child, to In the Fade, Fatih Akin’s German drama about woman losing her family to a neo-Nazi nail bomb. In Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here—the most ruthless film in competition—Joaquin Phoenix is a hallucinating hitman armed with a hammer on mission to rescue a teenage girl from sexual slavery.

If movies mirror the zeitgeist, this year’s Cannes selection suggests the world is a very scary place. One movie after another portrayed civil society as an embattled fortress, beset by chaos and brutality, with protagonists driven by sheer desperation. In Ukraine’s A Gentle Creature, a woman fighting to contact her imprisoned husband navigates a Kafka-esque maze of Russian corruption and debauchery. In Jupiter’s Moon, a Budapest doctor shamelessly exploits Syrian refugees, and plays Svengali to a bullet-ridden boy who has acquired miraculous powers of levitation.

Don’t ask what that has to do with Jupiter. You learn to distrust titles. Happy End, an acidic portrait of a disintegrating French family from Michael Haneke, does not end happily. In Josh and Benny Sadie’s manic thriller Good Time, starring Robert Pattinson as a bank robber on the run, no one is having a good time. And there’s no deer in The Killing of a Sacred Deer, in which doctors played by Colin Farrell and Nicole Kidman are helpless as their two children succumb to an incurable disease brought on by a curse.

It’s as if the zombie apocalypse has infected the art house. And in several films, art itself was under siege—notably The Square, an audacious and exquisitely dark comedy from Swedish writer-director Ruben Östlund (Force Majeure). Its protagonist is the director of a major art museum that is launching an installation that consists of a simple square, a safe space that offers a sanctuary of trust and caring to anyone who enters. The film was inspired by a similar project that Östlund helped create for a Swedish museum in 2015. But in the film he turns the art world on itself, satirizing the ludicrous extremes of conceptual stunts, such as an august exhibits titled “Piles of Gravel.”

The story unfolds as a Bonfire of the Vanities trail of ruin. The debonair museum director —played by Danish actor Claes Bang, who resembles Pierce Brosnan in his 007 days—sees his life unravel after he tries to trap a thief who stole his wallet and cell phone. One wrong turn and he’s driving blind down a road to hell paved with good intentions. The target at the heart of this satire is polite liberal hypocrisy, which is demolished in an excruciating scene where a half-naked performance artist acting as an ape runs riot at among diners at charity gala, pushing their patience (and ours) beyond the pale. The movie also features a real ape that roams a character’s apartment with no explanation. “I love monkeys,” Östlund told a press conference. “Everything should have a monkey in it.”

And these days it seems everything should have Elisabeth Moss in it. Moss, whose career is on fire after Mad Men and now The Handmaid’s Tale, shares a scene with the monkey in The Square. At every Cannes, you hope for a moment of outrageous comedy that disrupts the solemnity of all the serious art. Last year, Sandra Hüller offered a bunch of them in Toni Erdmann; this year it was Moss’s turn. Cast as a no-nonsense journalist, she performs a fantastically awkward sex scene, with the monkey uninvolved as a bored bystander. Without spoiling anything, let’s just say that there’s a tug of war, and never in the history of human conflict has a condom been stretched so far to milk a laugh.

As the Cannes straddled the worlds of film and television for the first time, Moss became a poster girl for that expansion—along with Nicole Kidman, both of whom starring in Campion’s Top of the Lake TV series. Kidman, the de facto queen of Cannes, also acted in three movies at the festival (Killing of a Sacred Deer, The Beguiled and How to Talk to Girls at Parties). And after her searing performance as an abused wife in HBO’s Big Little Lies, the Australian actress is enjoying a remarkable renaissance. “I’m turning 50 this year and I’ve never had more work,” she told me at a press conference. “That’s partly because I can work in films that were made to be shown on a small screen, and in films that are shown on a big screen. I have a foot in every area.” When I asked how she sees the rise of small screen formats affecting cinema, she said, “We need the opportunities. We need things to be seen. The world is changing and we have to change with it.”

Tell that to the Cannes film critics, who are famous—especially the French ones—for booing movies they don’t approve of, and who—for the first time I’ve seen, in all my years at Cannes—booed the moment the opening titles came up for Okja, a US$50-million action-adventure movie directed by the South Korean Bong Joon Ho and starring Tilda Swinton and Jake Gyllenhaal. What prompted the boos was the logo for the studio that produced it: Netflix.

Then things got weird. As the movie played, it was being projected in an oddly wide aspect cinematic ratio, cutting off the top of the image. The audience began yelling and clapping to draw attention to the projection problem, while the film continued to play for about five minutes. The screening descended into pandemonium. Not everyone in the digital age is fussy about aspect ratios, so some of the audience thought the uproar was a continuation of the anti-Netflix protest. Later, as speculation spread through social media, there were even suggestions that the projection of the film had been sabotaged by anti-Netflix forces.

According to the festival, the curtain masking the top of the screen was stuck due to a mechanical malfunction—a rich irony considering Okja hails from a studio that’s in the business of making projection technology obsolete. Eventually the problem was fixed, and the movie was restarted from the beginning, with another round of boos for the Netflix logo. Yet two hours later, when it ended, it received generous applause, without a single dissenting jeer.

That moment of chaos triggered the festival’s leading storyline—how cinema would handle the streaming giant’s disruptive presence. The festival has vowed that next year it will not admit movies that prohibit a theatrical window. But despite the initial backlash, filmmakers pointed out throughout the festival that the streaming giant offers more more creative freedom than the Hollywood studios. In interviews for The Meyerowitz Stories, both Ben Stiller and Adam Sandler leapt to its defence: “Their intentions are to make good movies,” said Sandler, whose Meyerowitz performance is drawing the best reviews of his career—and who has a new four-picture deal with the company. “I love the big screen,” offered Stiller, “but to be honest, since I’ve had kids I’ve watched a lot more at home. What’s positive about Netflix is they’re making the movies they used to make in the ’70s and ’80. The success Netflix is having is going to encourage the studios to take more chances.”

The other shift in cinema’s landscape, one much slower to evolve, is the emergence of women. Historically, Cannes has been a bastion of the male auteur, awarding the Palme D’Or to a female director (Jane Campion) only once in its 70 years. This year the odds improved a bit, with four of the 19 features in competition directed by women. And many films were powered by fierce female performances, from Diane Kruger as In the Fade’s bereaved mother, to Marine Vacth, who plays a woman sleeping with twin psychiatrists in François Ozon’s L’amant Double—an erotic thriller that, in a festival with no Canadian features, owed a double debt to David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers.

But nothing at Cannes had a more profound emotional impact on me than the sage female gaze that 89-year-old French director Agnès Varda brought to Faces Places, from both behind and in front of the camera. In this playful documentary, programmed out of competition, Varda teams up with a photographer named JR, who pastes giant images of ordinary people on walls in their villages. JR always wears a fedora and sunglasses, which Varda can’t convince him to take off. The film makes an issue of his resemblance to the young, bratty Jean-Luc Godard. Varda also alludes to her bittersweet history with Godard, whose haunting presence gradually invades the film with heartbreaking results.

It was strange, to say the least, to walk straight from Varda’s film to Redoubtable, a comic drama about Godard’s conversion from revolutionary filmmaker to Maoist ideologue. Set around May ’68, this pop biopic is a stylish but facile guilty pleasure, directed with an eye for the cheap gag by The Artist’s Michel Hazanavicius. The two films made for a diabolical double bill, but were separated by an unscheduled interlude—a bomb scare that forced the evacuation of the Palais.

Yet another moment in Cannes this year where the world beyond the frame kept intruding. In presenting Carne y Arena, Iñárritu says he was using virtual reality to “break the dictatorship of the frame—within which things are just observed.” But after removing the VR helmet and putting my shoes and socks back on, I exited through a white corridor of square screens, set into cubic recesses in the wall, each with a life-sized face of a refugee. Each stares into the camera, silent and unblinking, while his or her horrific story scrolls across the screen as text. Oddly, it was more moving than the virtual experience, which was too thrilling to allow for reflection. It was a reminder, at this Cannes in flux: Sometimes, you need the frame to make it real.