Judd Apatow adds some colour to his comedic palette

Comedy king Judd Apatow has yet to cast a person of colour in a lead role. That’s why his next film, ‘The Big Sick’, could be a big deal.

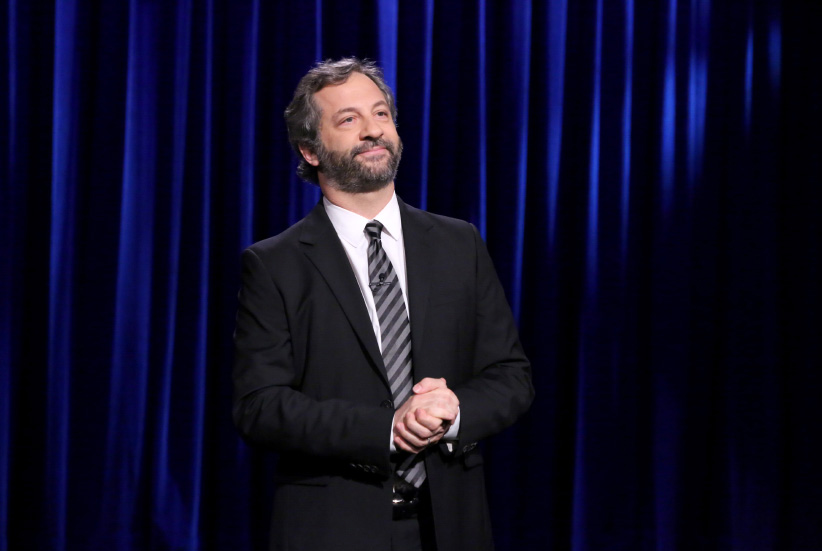

Comedian Judd Apatow performs on July 20, 2015 on The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon. (Douglas Gorenstein/NBC/Getty Images)

Share

Judd Apatow knows comedy. More specifically, Apatow knows romantic comedy: starting with his first blockbuster The 40-Year-Old Virgin, he’s produced a string of successful rom-coms, including Forgetting Sarah Marshall, Trainwreck, and the 2016 Netflix series Love, and he’s helped redefine the rom-com genre by imbuing his characters with relatable anxieties in essentially modern situations. “Apatow took a tired format—the rom-com—and brought it back to life with flawed characters and contemporary dialogue,” says Mark Breslin, co-founder of comedy incubator Yuk Yuk’s.

He’s made himself a “king of comedy,” as per a 2015 cover story in Rolling Stone—a Hollywood royal whose approval can knight the careers of lesser-known comics and actors. Take the stratospheric rise of the young talents in the short-lived 1999 TV series Freaks and Geeks, which in its single season churned out fame in James Franco, Jason Segel, Seth Rogen, and John Francis Daley, amongst others. He has the power to normalize, too: after making hits with comic riffs on male homosocial “bromances” (I Love You, Man, Superbad, Pineapple Express), it feels downright archaic to look askance at close friendships between two men.

But for all of Apatow’s innovations, Hollywood remains a system that prefers the tried-and-true, sticking with risk-averse formulas that will return their investments. For decades, that’s meant white men in lead roles telling jokes; it’s why it felt, in some circles, like some kind of plaudit-worthy revolution when the Apatow-produced Bridesmaids, starring the likes of Kristen Wiig and Melissa McCarthy, explored raunchy humour from a woman’s perspective in 2011.

But one frontier remains unchallenged for Apatow: a producer whose films follow white men like Dewey Cox, Ron Burgundy and Ricky Bobby has yet to feature lead characters of colour in his movies.

People are catching on. “The minority actors employed in his work tend to fall into small supporting roles, usually to offer advice to the white leads,” writes Robert Ham in Paste Magazine about Apatow’s typically neurotic show, Love, and the rest of his filmography. This, Ham says, is “a systemic problem.” Girls, the HBO show for which Apatow serves as an executive producer, has also endured criticism for failing to cast people of colour in significant roles.

Thankfully, 2017 will offer a potential turning point. The Apatow-produced The Big Sick, directed by Michael Showalter of Wet Hot American Summer acclaim, was one of the buzzier premieres from this month’s Sundance Film Festival—and it features Pakistani-American comedian Kumail Nanjiani enjoying the two-for-one pleasure of leading a major romantic comedy (he’s too funny to play on the sidelines) while also adding some much-needed colour to the zeitgeist of Hollywood humour that Apatow helped create. Best known for playing deadpan programmer Dinesh Chugtai on HBO’s Silicon Valley, Nanjiani is front and centre in The Big Sick—and it just so happens to be easily the best thing with Apatow’s name on it.

Penned by Nanjiani and writer Emily V. Gordon, his wife, The Big Sick dramatizes the couple’s own meet-cute and subsequent romantic drama, following an urgent medical illness that befalls Emily after months of dating in secret behind the backs of Kumail’s conservative parents. “Nobody has a good life story like that,” says Apatow at the film’s premiere, inadvertently explaining why seeking diverse narratives is important. “Who has a story that’s that?”

Playing Emily, Zoe Kazan has charming on-screen chemistry with Nanjiani, who plays a fictionalized version of himself in the film. The idea that “chemistry” is critical for the success of a rom-com in general is obvious, but with The Big Sick, given its premise, the emotional honesty of the story had to include perspectives from both sides of the hospital bed—a key challenge in the writing process, especially since immediately before Emily’s sickness, their relationship had, by the looks of it, ended.

“This can’t be a movie where a woman falls into a coma so a guy can have an epiphany,” says Nanjiani, discussing how to drive a romance forward with only one half of the dynamic actively conscious. Having lived through that difficult chapter in their love story, Gordon elaborates: “She was not participating in the relationship, so it would have been weird if she was immediately like, ‘Yay, thank you!’ And fell back into his arms.”

Another shared quality across Apatow’s films is how they resonate with people—after making them laugh, of course. That’s Apatow’s signature move: his ability to find common comedic ground with audiences through their pathos and their anxieties. So it’s significant that much of The Big Sick’s poignancy come from Nanjiani’s conflicted faith in Islam and his struggles with the expectations of his conservative mother and father. It shows that The Big Sick isn’t just a romantic comedy: It’s a movie about an immigrant experience, in Chicago, unfolding as a mainstream hit.

MORE: Cristela Alonzo on the importance of diversity on screens

Movies and shows like Aziz Ansari’s Netflix series Master of None—a traditional dating sitcom that doubles as a depiction of working as a brown actor in Hollywood, and has earned a hotly anticipated second season—suggest there’s clearly a demand for stories from people of colour. Comedy, after all, has the ability to invite, rather than exclude, when the right common ground is struck, even if the narrative isn’t something inherently familiar to audiences.

MORE: Our Q&A with Aziz Ansari on ‘ethnic casting’ and a revolutionary show

The Big Sick, then, becomes an opportunity to challenge clichés. “I still feel like when someone thinks of a Muslim, they get one image in their head,” Nanjiani says. “Like, when you go to a theme park, you see Muslims riding rollercoasters and eating ice cream. Why doesn’t anyone think of those Muslims when they think of Muslims?”

But it’s also unafraid to mine Muslim stereotypes for huge laughs in a script already laden with pitch-perfect gallows humour. In one scene, Emily’s father, played by Ray Romano, grills Nanjiani about his personal stance on the 9/11 attacks. “Oh, anti,” he responds, taking a bite of hospital food. “We lost 19 of our best guys.”

Thankfully, The Big Sick isn’t just 119 minutes of terrorism jokes. Nanjiani’s Pakistani upbringing comes through in domestic situations translatable far beyond their Urdu language barrier, like family dinners he endures to humour his mother’s attempt to arrange a marriage, a pain point for Emily when she finds out. Arranged marriage may not be something the average person in North America understands, but disappointing your parents? Making mistakes in a relationship? These are the worries everyone loses sleep over—and Apatow’s co-signing of these refreshingly specific universalities bodes well for the future of comedy.

After all, finding common ground is, at its essence, Apatow’s gift—and, thanks in part to the co-sign of the man behind Funny People, all funny people might just have a chance to tell their own specific stories.