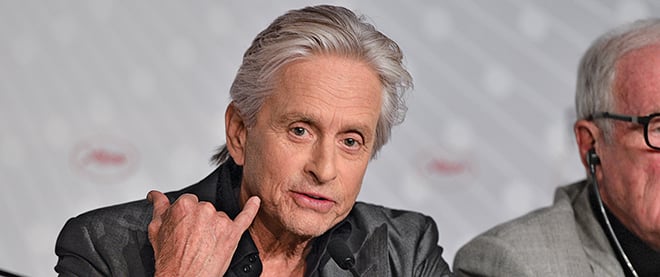

Actor Michael Douglas on playing Liberace, kissing Matt Damon, and his wife’s bipolarity

In conversation with Brian D. Johnson

Photograph by George Pimentel

Share

In Steven Soderbergh’s Behind the Candelabra, Oscar-winning actor Michael Douglas stars as piano showman Liberace, the most flamboyant gay superstar never to come out of the closet. The film is based on a book by Liberace’s long-time lover, Scott Thorson, who’s played by Matt Damon, often wearing just a spray tan and a Speedo. Douglas, 68, made the movie after recovering from stage-four throat cancer. Maclean’s spoke to him this week outside Cannes before the film’s premiere. Behind the Candelabra airs on HBO May 26.

Q: This is some way to bounce back from cancer, playing a raving queen in bed with Matt Damon—and speed piano. Which was harder?

A: The piano. People knew Liberace, so you had to catch that essence, without impersonating him. He was a big Polack, so I had to get over the physical differences. I dove into his voice first, which was unique, and then the piano work. I don’t play piano.

Q: You could have fooled me.

A: I spent a lot of time, hour after hour. Copy the hand movements. At the beginning of the movie is the boogie-woogie number where I’m playing with one hand and talking to the audience. We a had little brunch before we started shooting, and Dylan, my 12-year-old, sat down at the table and proceeded to do a very good imitation with perfect timing of the piano and the entire monologue. Matt says, “That’s when I realized his old man must have been rehearsing an awful lot if his kid could be playing that well.”

Q: You were shooting Traffic 13 years ago when Soderbergh said he could see you as Liberace.

A: I thought he was messing with me. I tried a couple of accents on him, but it wasn’t until ’06 when he found the book by Scott Thorson. It turned out to be a godsend, not only because it was one of the best parts I’ve ever had, but because I was recovering from my cancer, I had issues with my oldest son incarcerated in federal prison, and I didn’t know I had a career. It was totally inspirational.

Q: How did the cancer diagnosis hit you?

A: I’d gone through two full rounds of ear, nose and throat guys and scans and each time had been given a dose of antibiotics. I’ve got a farm up in Quebec not far from Mont Tremblant. Dr. Saul Frankel—who’s at McGill and also works at Mount Sinai—is a friend of mine, and he simply took a tongue depressor, as close as you and I are, and I’ll never forget the moment. His eyes, I could just tell, and he slowly pulled it out and said, “I guess we have to do a biopsy.” Then I’m down at Sloan-Kettering and they say I’ve got stage four, so I was reeling pretty fast. Then to have this opportunity when you weren’t even sure you had a career any more.

Q: Behind the Candelabra has the most prodigious gay love scenes between two A-list actors in Hollywood history. Did feel you were doing something groundbreaking?

A: No. I got the sense we were doing something exciting. This is what you dream for: good material, good director, great co-star. I mean, obviously I knew it would be a hoot.

Q: Let’s cut to the chase. Everybody wants to know what it was like to kiss Matt Damon.

A: You know, it doesn’t matter, does it, if it’s a man or a woman. It’s a kiss. We had to show affection in some places, love, passion in other places. A kiss is just a kiss. I mean, we’d have our fun. You know, “Matt, what flavour lip gloss would you like me to wear today?” When I see the movie I’m so proud that a few minutes go by and I forget that it’s Matt and I, and halfway through I forget it’s two guys. The arguments sound the same as arguments a guy has with his wife.

Q: You grew up watching Liberace on TV?

A: Yeah. I never thought about the gayness. He just looked like he was having so much fun. And that whole idea of talking directly to the audience, you just went along with him. He made you happy. And he’s finally getting acknowledged for all the Elton John, Lady Gaga, Madonna theatrics now that people are looking at his old costumes.

Q: You took the film to HBO because no studio would touch it. Was that homophobia?

A: No, I think it’s just pure economics. They think, “This is a picture that will only appeal to a gay audience, so what’s the population?” I can’t blame them. I can blame them for being very narrow-sighted and wanting to put all their energies into enormous sequels or action pictures. They are just not bothered with smaller pictures, although I know Jerry Weintraub is getting a great degree of satisfaction now as these studios have called and said, “Boy, did we make a mistake.”

Q: Soderbergh is so fed up with the studios he’s sworn off making movies. Is he serious?.

A: Well, he’s getting out. I think he’ll be doing a couple of long-form cable series, which he’ll produce and have that freedom not having to worry about distribution because they’ve got that built-in subscription audience. I understand. I’ve gotten burnt the last few years on a couple of little independent films where you get paid nothing, you work your ass off, there’s no marketing budget except you going on every talk show. But you’re seeing it all over. I mean, these disasters at NBC, with the morning show, and how Matt Lauer and Jay Leno could be handled much better. These are people who don’t really have a concept of talent: it’s an employee, period.

Q: The fact that the Liberace film is Steven Soderbergh’s swan song, did it add pressure?

A: No. I was just so happy that he had Magic Mike, which he’d made a small fortune on. So I said, “If you’re going to retire at least you’re going out in style.”

Q: You’ve had a lot of personal pressures, and they’ve all been in the public eye—whether it’s cancer or your son in prison on drug charges or your wife, Catherine Zeta-Jones, revealing she’s bipolar. Is it tough having your life out there like that?

A: Not anymore. In this whole digital age, where everything is so exposed, rather than trying to keep something private, you try to get out ahead of the curve and limit the amount of gossip. I feel for these younger guys. I don’t know how they do it as a young guy or woman, with all these cameras in the bathrooms and this and that.

Q: When Catherine decided to go public last year about her bipolar condition, did you discuss that?

A: We talked about it but she really made a decision. It was an issue. With bipolarity, what happens to a lot of people is you feel good and you just throw away the meds and say, “I don’t want be on them anymore.” Of course that’s the worst possible thing you can do. If you want to talk to your doctor they’ll take you off these things—but all of a sudden she was feeling fine and got rid of everything. Then it flips you for a whole tailspin, and so basically it was her 30,000-mile checkup, getting things balanced out again, and she’s doing great. She’s out tomorrow. She’s going to be fine.

Q: Can I ask about your eldest son, Cameron? While serving a five-year drug sentence, he’s just been slapped with another five years for dealing in prison. You’ve said he’s been targeted because of his family name.

A: Cameron received the longest sentence in the history of the American penal system for a prisoner having drugs in prison. And, mind you, his drugs were opiates and an eighth of a pill of Suboxone, which is a methadone-like treatment. He was a heroin addict and he was obviously self-medicating. He has never received rehabilitation because the doctors insist you don’t get rehabilitation until the end of your term, which makes not a lot of sense. There’s been a slew of prisoners selling heroin in jail and everything else, and I’ve been hard-put to find out how he could have received the most severe sentence. And the idea that I have no visitation rights for two years—I do not possibly see how it helps a non-violent drug convict. We have more prisons than any place in the world, more citizens incarcerated, and about a third are tied into non-violent drug arrests, so I’m afraid this is going to be an issue—besides elimination of nuclear weapons—that I’m going to get involved in.

Q: Now that you have this second wind, how do you see the final act of your life unfolding?

A: Well, I’m 68 now, although [my father] Kirk’s 96. I have to look at the end of cancer as the end of the second act, and we had a dramatic flourish there. It certainly makes me much more conscious of how I choose to spend my time. I’m very grateful to have a career and a number of other pictures coming up. Last Vegas is coming out Nov. 1. It’s sort of an altacocker [Yiddish slang for “old fart”] version of The Hangover. I play a guy who’s going to marry a girl 30 years younger and my old buddies decide, “Let’s have a bachelor party, we’ll meet in Vegas”—Bobby De Niro, Morgan Freeman, Kevin Kline and myself. None of us had ever worked with each other. We had a lot of fun, which is always the kiss of death for the movie, but it tested through the roof.

Q: So you’ve got yourself a franchise?

A: They’re writing a sequel. Next week I’m starting a Rob Reiner picture with Diane Keaton, called And So it Goes.

Q: Movies about seniors are suddenly hot.

A: Well, they’re back in the theatres. We’ve done this full circle where movies were designed for kids to see, but now they all watch them on their iPads. The old folks want to get out of the house.