Was Winnipeg right about Phantom of the Paradise all along?

One Canadian city, and Daft Punk, kept alive a cult flop that turns 40 this year

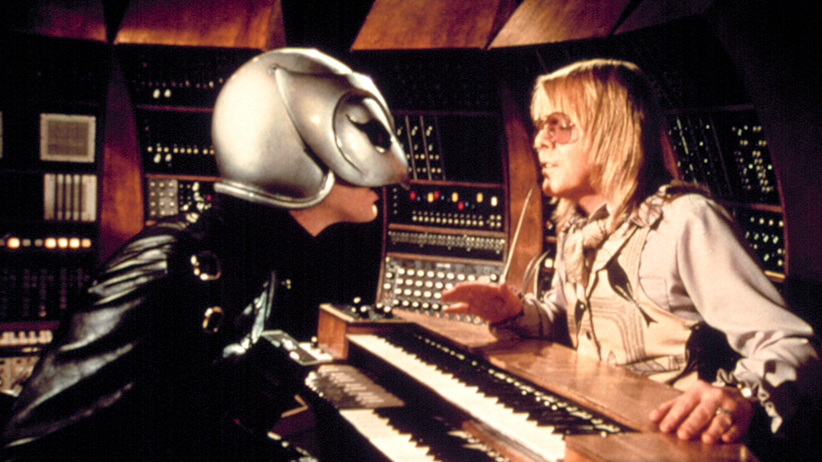

PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE, William Finley, Paul Williams, 1974, TM & Copyright (c) 20th Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Share

It’s tricky to predict the patterns shaping a movie’s cult success. A few hardened horror fans import a Japanese flick about a haunted video tape and, next thing you know, the director of Pirates of the Caribbean is remaking The Ring. A handful of camp addicts scoop up copies of the striptease fiasco Showgirls and soon, critics are saluting it as a misunderstood piece of picaresque satire.

Still, the underground revival of Phantom of the Paradise—Brian De Palma’s 1974 musical-satire horror-comedy whatzit—stands as one of the weirdest, and unlikeliest, in the murky annals of cult cinema. The film stars William Finley as the hopelessly earnest singer-songwriter Winslow Leach, and features actually hopelessly earnest singer-songwriter Paul Williams (who wrote for the Carpenters and Three Dog Night) as Swan, a Mephistophelean record producer who steals Leach’s music and dilutes it to the lowest common denominator. Enraged and mutilated after getting his face smushed in a record press, Winslow shrouds himself in leather, hides his disfigured gourd behind a silver bird-like helmet and wreaks havoc on Swan’s decadent rock club, the Paradise.

The film was a commercial and critical failure: too weird (one character chuffs palmfuls of coke while wearing a belt made of antlers), tonally schizophrenic (vacillating between goofball comedy and Greek tragedy, often within a scene) and unusually prescient (it forecast the ascendancy of goth rock and reality TV) to find an audience.

Save for two places. There was Paris, where discerning aesthetes operate on another altitude of ahead-of-the-curve irony (see: their appreciation of Jerry Lewis). And, much more improbably, there was Winnipeg.

Across North America, Phantom opened and closed within a week. In Winnipeg, it ran continuously for four months following its release, then on and off until 1976. Its soundtrack album, composed by Paul Williams, was certified gold in Canada, thanks pretty much exclusively to Winnipeg sales. “The lesson for me,” says Williams over the phone from L.A., “is don’t measure your successes—or your failures—too quickly. If nothing else, it made me fall absolutely in love with the ’Peggers. What were they getting that the rest of the world wasn’t?”

Rod Warkentin was born and raised in Winnipeg. He saw Phantom with his sister at the Garrick Theatre when he was 10. He estimates he saw it 29 more times in its initial Winnipeg run. “It caught on with word-of-mouth,” he explains. “Something about it appealed to the youth. Anyone who’s our age who grew up in Winnipeg, you ask them about it and they’ll say, ‘Oh yeah, it’s phenomenal.’ ”

In 2004, after reading an article marking the film’s 30th anniversary, Warkentin and some other fanatics organized “Phantompalooza”—a fan get-together held at the Garrick, featuring stars Finley and Gerrit Graham, who played a lisping macho rocker called “Beef.” The next year, they flew to L.A. to invite Williams to the next Phantompalooza. He agreed, hosting a concert during the 2006 shindig. For the 40th anniversary this year, Phantompalooza relocated to L.A. for a blowout last weekend that reunited most of the original cast (Finley died in 2012).

In fact, since that initial bellyflop, Phantom’s popularity has snowballed. The story goes that Guy Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk met as teens at a Paris screening, launching a creative partnership that culminated in a collaboration with Williams on their 2013 hit record. “They saw Phantom of the Paradise together more than 20 times,” Williams boasts. “It’s their favourite movie!”

It’s odd drawing a line between French techno-pop icons and 50-year-old Winnipeggers. But Phantom has a universal quality. “I’m reluctant to call myself a sex symbol, but Swan was sexy,” says Williams. “I think it showed people that you could still get things if you were the runt of the litter.” For Warkentin, Phantom’s recuperation has more to do with the unforgiving pessimism that boils beneath the campy veneer. It’s the sort of thing that would naturally play with self-persecuting adolescents, from Paris to the ’Peg. “Nobody gets what they want in the film,” he notes. “No one wins.”