Rudolph, the superficially popular reindeer

The beloved Christmas story of Rudolph has a message that offends many adults, but makes perfect sense to kids: Life is cruel, but people will pretend to like you if you become a success

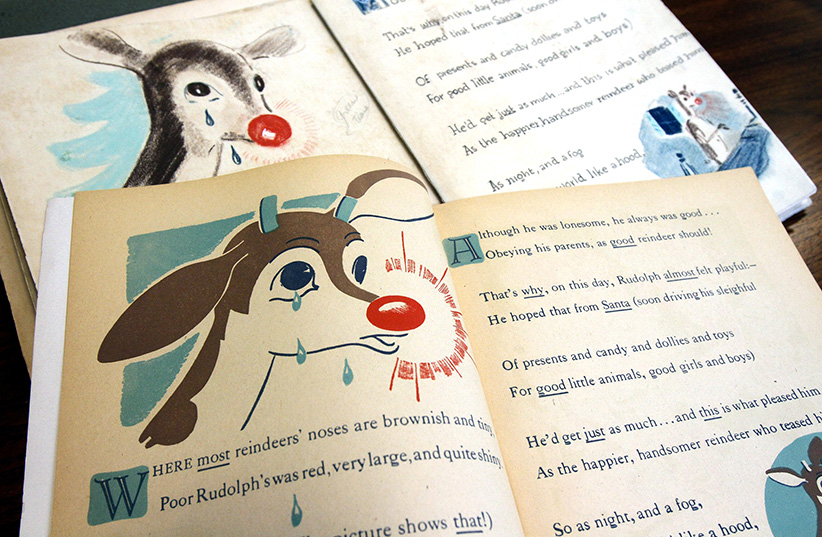

A first edition of “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer”, bottom, and an original layout, top, part of a special collection at Dartmouth College, are displayed on Tuesday, Dec. 20, 2011 in Hanover, N.H. The book is from the estate of Robert May, a Dartmouth graduate who wrote the famous story in 1939 as part of a Montgomery Ward marketing campaign. (Toby Talbot/AP)

Share

It’s Christmas music season again, and time for the usual arguments over the most controversial holiday song of all. No, not Baby, It’s Cold Outside. It’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Every year people notice what a depressing story this really is: in brief, a deformed kid is constantly made fun of by his peers until his deformity proves useful to the boss, at which point all the other reindeer pretend to like him. What kind of message is that?

That’s the way many of us react to the story when we’re no longer children, and it shows, in a way, how adults are more innocent than children. To a child, the casual bullying of the other reindeer, as well as their sudden about-face when Rudolph becomes popular, are perfectly understandable; it’s not nice, but it’s real. Because children are more open than grown-ups about bullying people who are different, kids accept the world of Rudolph as a reasonable facsimile of their everyday lives. Once we grow up, we expect bullying to be hidden and popular culture to have improving, uplifting messages, so we start worrying about what kind of message Rudolph is sending our kids. But it’s no different than the messages they receive every day at school.

The message of Rudolph isn’t really cynical, though. Martha May, one of the daughters of Rudolph’s creator, Robert L. May, said that he was telling children “that being an underdog was OK if you found your one talent and used it. You could be a success.” According to some accounts, May was also moved to write the book because his wife had cancer and his other daughter, Barbara, wanted to know why her mommy wasn’t “just like everybody else’s mommy.”

May’s original book, on which the song is based, is a sort of sequel to “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas,” the famous poem that named Santa’s reindeer. The Rudolph book has the same metre and begins “‘Twas the day before Christmas,” and it imagines what would happen if there was a reindeer who didn’t fit in with the others—whereas in the original, they all had different names but seemed to be exactly alike. The point of the story, any way you look at it, is that being different isn’t a bad thing, and sometimes it’s good to be an outcast.

But unlike a lot of children’s stories on that same theme, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer doesn’t imagine that others can really learn to accept people who are different. It offers a more tough-minded lesson: others will accept you for being different if it’s in their interest to do so, or if you can offer them what they want. So in May’s book, once Rudolph has proved his worth to Santa, the other reindeer feel ashamed at having been so wrong about Rudolph:

Oh boy, was he proud, as they came to a landing

Right where his handsomer playmates were standing!

These bad deer who used to do nothing but tease him

Would now have done anything . . . only to please him!

The song, which was written 10 years after May created Rudolph, compresses the story to fit in the limits of a 32-bar pop song, and does it pretty brilliantly—there’s not a wasted word in Johnny Marks’s lyric. But because of the compression, it doesn’t make it as clear as the 1939 poem that Rudolph’s triumph is the other characters’ humiliation: like Cinderella, he gets the satisfaction of being elevated above the characters who looked down on him. And like the story of Cinderella, it appeals to children because it doesn’t tell them nasty people can suddenly turn nice. Kids would dismiss that as a lie. But they’ll believe that if they had a special talent, the nasty people would suddenly act nice to them.

One other part of the story’s appeal to children is that Rudolph doesn’t really have to work hard to achieve success. The idea that rewards come to the people who work hard and take risks—that, again, is something that appeals more to adults, who want to believe that putting in extra hours and saving extra money will pay off in the end. Children don’t have a lot of power to improve their lives by their own actions, so they respond to passive characters like Rudolph: he’s saved when someone else comes along and recognizes his potential. Grown-ups might find it shocking that Rudolph is rewarded for doing nothing, just being who he is; grown-ups might not like that he makes friends who aren’t really his friends at all, and are only “loving” him because he’s the cool “in” thing. But the story isn’t for grown-ups. It’s for kids, and kids have a more mature view of life.