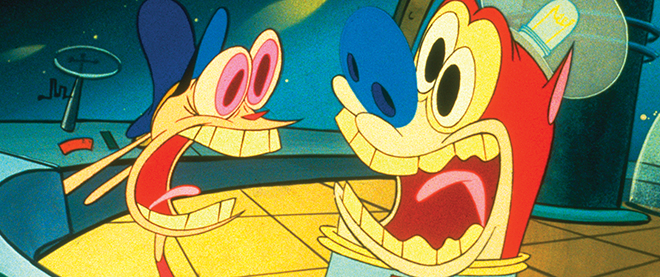

Ren & Stimpy: Never before, never again

… and for good reason, as Jaime Weinman explains

Nickelodeon

Share

Nostalgia for 1990s kids’ shows is big today, but there’s been comparatively little attention paid to perhaps the biggest ’90s hit of all: Ren & Stimpy, the creation of Canadian cartoonist John Kricfalusi. Its original run, from 1991 to 1996, established cable TV as a major outlet for smart cartoons. “People just love the subversive brilliance of it,” says Thad Komorowski, a U.S. animation blogger who has just written a book about the show, called Sick Little Monkeys. With ’90s nostalgia sites like Buzzfeed choosing to focus on more child-friendly shows like Rugrats, the new book might be the best way to remember how large a big dumb cat and an angry chihuahua loom in animation history.

Kricfalusi founded Spumco, Ren & Stimpy’s production company, after working on shows like Fonz and the Happy Days Gang where everything was done in the least creative way. “Layout artists just photocopied model sheets and cut and pasted them into new positions,” recalls Canadian animator Mark Mayerson. Film archivist Reg Hartt adds that by the ’90s, outsourcing had created a system where “animation, ink and paint and everything else was scattered around the world.” Though not easy to work for, Kricfalusi became a refuge for people who hated those compromises as much as he did. “He wanted it to look great,” says Canadian cartoonist Bob Jaques, who supervised the animation for many Ren & Stimpy cartoons. “Other studios did not care what the work looked like as long as it was good enough to broadcast.”

When Ren & Stimpy premiered, adults and children alike became fans of Kricfalusi’s attempt to revive wild physical acting. Even The Simpsons, which started the season before, depended more on writing than animation, but Mayerson says Kricfalusi “rejected the idea of stock poses.” Instead, Jaques says, “actions and acting were, as much as possible, tailor-made,” with stories told more through drawings than dialogue. The book chronicles how new techniques in animation and painting were used to create episodes like “Stimpy’s Invention” (with the “happy, happy, joy, joy!” song that became a ’90s catchphrase).

Unfortunately, the Ren & Stimpy story wasn’t just about improving animation, but also about how costly it is to make it. “Ren & Stimpy was easily the most expensive TV animation done in history,” Komorowski says, thanks to Kricfalusi’s perfectionism and missed deadlines. “They had to repeat the first episode because the second episode was late,” Jaques recalls. Finally Nickelodeon fired the creator, though Komorowski says that ironically, the scheduling problems didn’t end: “The cartoons were always late, both before and after the takeover.” Though Kricfalusi returned for a short-lived revival in 2003, Ren & Stimpy’s time as a phenomenon was over.

Since then, there has been no real successor to Ren & Stimpy, even as kids’ shows have imitated its groundbreaking bodily-function humour. Komorowski puts some of the blame on executives who “want the show’s successes imitated in the most superficial, cheapest way.” But Jaques adds that there may be a bias against the kind of animation Kricfalusi fought for. “Generally speaking, the writers do not like anything that will upstage their writing, so anything cartoony or exaggerated that competes with their work is removed.” Some of today’s most acclaimed TV cartoons, like FX’s Archer, have characters who barely move or change expressions: the style Ren & Stimpy was rebelling against may have become the style TV cartoon makers prefer.

Still, Kricfalusi’s early success may have left a mark on the animation business. He remains a big enough name that he was invited to contribute a couch gag to a 2011 episode of The Simpsons, with characters twisting their bodies out of shape, and used Kickstarter to raise money for a new film starring a Ren & Stimpy supporting character, right-wing maniac George Liquor. And while Komorowski doesn’t think post-Ren & Stimpy cartoons measure up to those first episodes, he thinks they raised the bar for animation enough that “there is no way it can regress back to what it was in the ’70s and ’80s.” No matter how hard executives may try to make that happen.