These vintage photos celebrate Black communities in Canada through the decades

“There is an onus for us to document ourselves. I certainly wasn’t waiting for anyone to tell me about Black Kitchener-Waterloo—it was incumbent upon me to do so.”

Share

Growing up, it was rare for Aaron T. Francis to see his grandfather Roy without a camera in hand. “He was one of the most influential people in my life,” says Aaron. “He would go out of his way to teach me about construction, mechanics, electrical engineering and Black history.” Roy, a welder and self-taught photographer, was born into a rough part of Kingston, Jamaica, in 1933. He immigrated to England before coming to Canada in 1965, where he worked for an aerospace company and became part of a close-knit Jamaican community in Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario.

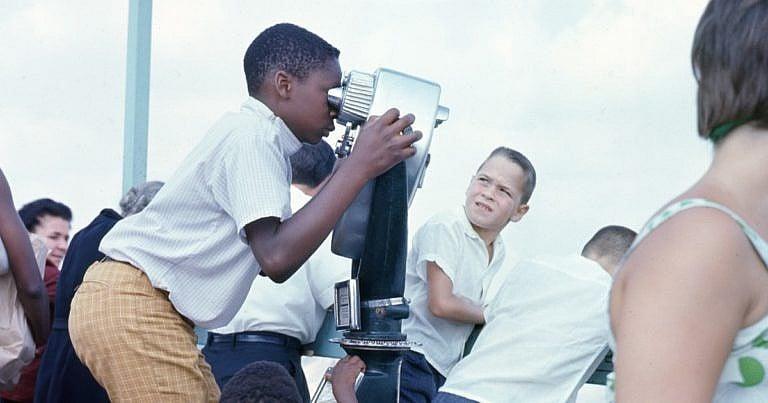

Roy captured the everyday nuances of Black life for six decades, documenting idyllic suburban scenarios and mundane moments of joy on film or his Rolleiflex. He shot photos of family members spinning records, depicting a thriving Jamaican community that bonded over music. Other snaps reveal the loneliness and hardship of being Black in Canada.

In 2018, Roy moved into a long-term care home. While preparing his grandfather for the transition, Aaron discovered a treasure trove in Roy’s garage: thousands of photos showing family and community history. Aaron, a political scientist pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Waterloo, is also an art history lover, and he was amazed at how his grandfather captured Black Canada. “I knew he was a photographer, and that he was good,” says Aaron. “Then I found these photographs, and I couldn’t understand why I hadn’t seen them before.”

After Roy died that year at age 85, Aaron decided it was important to honor his grandfather publicly. In 2019, he started the Instagram account @vintageblackcanada, where he posts pictures from his grandfather’s collection. It is part of Aaron’s effort to remember and preserve history; Roy made sure his grandson knew that Black people have always been part of this nation’s fabric, from 19th-century settler communities to 20th-century entrepreneurs. And yet their history is relatively unknown. “Erasure is a two-way street,” says Aaron. “Others can erase you, but you can also forget what you had.”

The digital archive gained more traction in 2020, after the murder of George Floyd. Aaron has always been aware of how Black people are stereotyped in the media, and the negative depictions of his community underscored the importance of documenting them in a way that maintained respect and dignity. “I wanted to see us being joyful and candid, and not necessarily for the world’s entertainment,” he says. “There is an onus for us to document ourselves. I certainly wasn’t waiting for anyone to tell me about Black Kitchener-Waterloo—it was incumbent upon me to do so.”

READ: A new Art Gallery of Ontario exhibit looks at the beauty and culture of the African diaspora

“My grandfather Roy Francis was one of the most influential people in my life, and I recognize an innate beauty in his work. This photo of him was taken in England in either 1960 or 1961. He experienced a lot of racism there and wasn’t a fan of the industrial working conditions.”

“My grandfather went out of his way to create photographic moments, and he would often take the same photo three or four times. He cared a lot about symmetry. This photo, taken in 1969 at my grandparents’ home in Waterloo, Ontario, was most likely staged. Everyone is wearing their Sunday best and looking in a different direction, with only my grandmother facing the camera—an intentional decision on his part. My mom and uncles, pictured here, faced racism at almost every turn growing up in 1970s Kitchener-Waterloo. I’ve heard their worst stories, but they didn’t let those experiences make them feel inferior. They fostered in me a drive to succeed.”

“My grandmother Muriel attended the third Toronto Caribana in 1969 with my mom, Aunt Maggie, Uncle Dave, Uncle Mark and Uncle Errol. From the moment I could walk, my family took me to eat and dance at Caribana, an experience that transported us back to our Jamaican roots. In the 1990s, Caribana was an annual rite of passage for Black Canadians. We’d rent a bus, play soca music and have picnics.”

“You cannot underestimate the importance of a Black family’s basement. We danced and played Jamaican music there when clubs and radio stations weren’t willing to. In this photo, my grandfather Roy and Uncle Errol are in our Waterloo basement, where we had a leather-wrapped bar, a microphone, speakers, two turntables and a mixer, which my grandfather taught me how to use.”

“This is my uncle Dave, who’s loading up an eight-track tape in the basement. My grandfather often exposed us to new music, and Dave grew up to be a dancehall DJ. Our family listened to Jimi Hendrix, reggae singers like Beres Hammond and Luciano, dancehall DJ Super Cat, and even Black Sabbath on occasion.”

“I don’t know the woman in this picture. It’s part of a series of photos that my grandfather took at a wedding, where the woman was a guest. One time, I showed this image to a white woman, and she asked me why the woman looked so angry. I found that reaction interesting because I feel like she exudes confidence.”

“On the right is my great-grandmother Jane Ruddock in Jamaica during the early 1980s. She was born in Westmoreland, Jamaica, and married my great-grandfather, a Maroon descendant. He came from a community of formerly enslaved Africans who, upon their arrival in Jamaica, successfully revolted against the British in the 18th century. Standing next to Jane is her sister Kathrine Medoria Smith, commonly known as Miss Katie, who helped raise Jane’s nine children.”