Tommy Chong recalls his months in prison with the Wolf of Wall Street

Chong on his time with cellmate Jordan Belfort

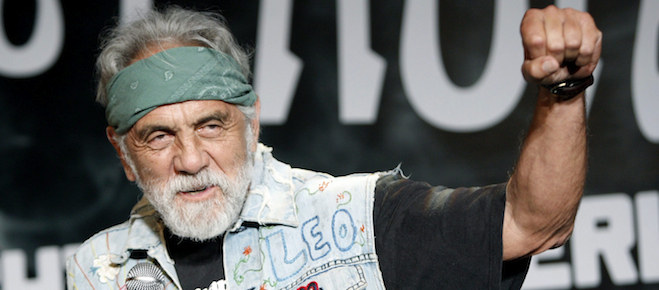

Comedian Tommy Chong performs during a news conference announcing his upcoming tour with Cheech Marin, “Cheech & Chong: Light Up America” in West Hollywood, Calif. on Wednesday, July 30, 2008. (AP Photo/Matt Sayles)

Share

At 75, Tommy Chong has become a man of many titles: actor, singer, comedian, marijuana advocate. But the high-flying Edmonton native has earned himself a whole new moniker: the former cellmate of Jordan Belfort, the now-infamous Wolf of Wall Street. In 2004, while serving a nine-month sentence in a low-security California prison he calls “Camp Cupcake,” Chong was joined by Belfort, whose narrative of drugs, fraud and eventual 22-month incarceration is retold in Martin Scorsese’s latest movie. Maclean’s reached Chong in California to talk about the life lessons he gave to Belfort, the terrible first draft of the autobiography that inspired the buzzy film, and the vital importance of onions.

Q: So how did you first meet the Wolf of Wall Street?

A: When Jordan walked on the scene, I didn’t know who he was until someone reminded me of the movie Boiler Room and even then, it didn’t make much difference—we’re all dressed in the same prison garb. There was nothing outstanding about him, other than the fact that when I met him, he was playing backgammon and having a conversation with another guy and talking to me at the same time. He was one of those geniuses who can do many things at the same time. And then we ended up in the same cubicle, so at night he’d tell me these great stories, which became (the book) The Wolf of Wall Street.

Q: What role did you play in the writing of the book?

A: Well, I was working on a book myself, so every evening or every chance I got I would sit and write. Jordan got curious and wanted to know what I was doing, and I told him I was writing a book, and he said, “I’m gonna write.” So he started kind of emulating me—every night, we’d sit together, he’d write his pages and I’d write my pages.

After a while he showed me what he had written, and it was the only time I had critiqued someone really heavy—usually when someone writes something, you say, “Oh yeah, that’s great, keep going.” But I knew instinctively he had a lot more to offer than what he showed me. … I told him, “Honestly, you haven’t really written anything.” He had been working on it for a couple of weeks so he was really pissed off. He snatched the papers back, and I said, “No, you’ve got to write those stories you’ve been telling me at night. Your real life is much more exciting than any kind of imaginary story you could come up with.”

Q: What was the original story he wrote?

A: The original was fiction—it was a whodunit, a Dashiell Hammett noir. I think he was reading the guy who wrote The Pelican Brief, so it was along that line. I mean, it was good, but it wasn’t the stories he was telling me. It was just pedestrian. You could pick a book up anywhere and read that thing. Nothing stood out. … After I gave him the bad critique, he didn’t talk to me for a good month. And in fact, he never did show me more pages. But when I got out—I got out before him—and he was on probation, he came by my house beeping his horn and he was yelling from the street, “I wrote a book. I’ve got a copy for you,” and he gave me The Wolf of Wall Street. (Pause.) Which I haven’t read, by the way (laughs).

Q: You two were also friends with PGA Tour caddie Eric Larson, who spent 11 years in jail for selling cocaine. What was your favourite memory of hanging out with both Larson and Belfort?

A: Larson, to this day, is not that fond of Jordan. Larson is straight-arrow. … Larson was the cook. He was also the gardener, he had this incredible garden growing. And the most wanted commodity in prison was the onion, because there were so many ethnic-type prisoners and everybody cooks with onions for health reasons and for taste and everything. So an onion would be the equivalent of a package of cigarettes in the old days: you could barter with onions.

But you could only buy one onion a day, and Larson grew onions in the garden, so we had a Fort Knox growing in the garden, and he would use the onions and the fresh vegetables to cook for us, but there was one rule: when you ate with Larson, he did the cooking, but we did the cleaning up. Well, when Jordan joined the group, I insisted, “Come on, he’s one of us.” [But] he used to hire people to do everything for him. … When it came time to wash the dishes, he hired other inmates to wash the dishes for him! So Larson kicked him out.

Q: It sounds like you see yourself as something of a father figure to him.

A: I’m very proud of him. I’m proud of everyone I met in prison. They’re part of my closest friends. … And my wife Shelby loves Jordan. All women come around to him. He’s such a charmer. He always was so sweet to everybody—that’s one of things about him. I mean, he’s a con man.

Q: Did you pass on any lessons to him?

A: The problem when you’re doing something illegal is that you know what you’re doing. There’s a great deal of remorse and there’s a great deal of guilt associated with it. You’re lying to everybody: you’re lying to your parents, you’re lying to your kids. The only person you can’t lie to is yourself. Jordan couldn’t enjoy anything because he had to do all those drugs to quiet down those voices and his conscience. So that’s the catch-22 with success through thievery: you can’t enjoy your riches so you end up debauching—hookers and drugs and gambling. You throw the money away because it really is a burden.

What I showed Jordan is how easy it is to just be who you really are, and that the little things mean a lot. For instance, when you get older in jail, one of the things you pass around is cushions, little squares of foam rubber, because there’s no soft chairs in prison, there’s nothing padded, so the old guys walk around carrying their cushions. Jordan and myself, we learned to appreciate the little things, and by appreciating the little things the desire to have the stuff disappears. … What Jordan learned is that when you’re intelligent as this guy is, and you don’t need anything, you own the world. Your life becomes so beautiful—it’s one beautiful moment after another.

All I really did was remind him was who he really was, and when he came to grips with that, then there was nothing else he could do except enjoy whatever comes his way now.

This interview has been edited.