Yellowjackets is about cannibalism. It’s also about how we face trauma.

At the core of the show is a chilling question: how far would you go to survive?

Share

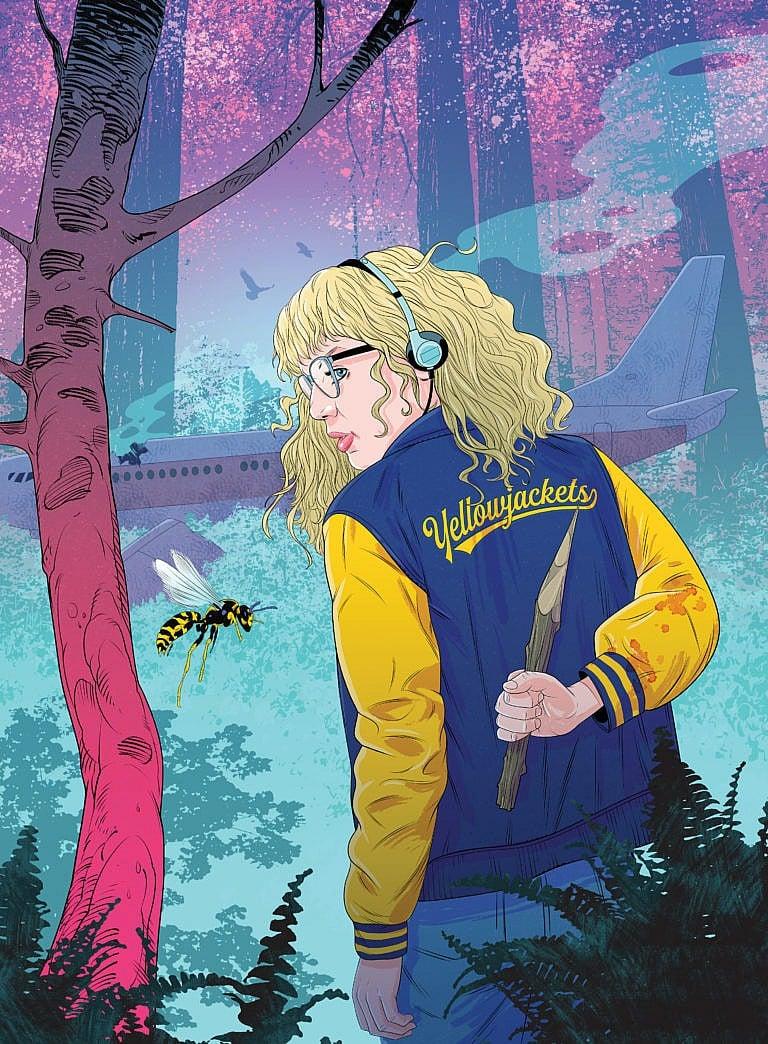

Under what circumstances could you be persuaded to eat human flesh? You may already know the answer. (The only acceptable one, by the way, is: extreme duress.) If you happened to be one of the many millions of viewers masochistic enough to mainline the first season of Yellowjackets, Showtime’s breakout survival sensation, then cannibalistic hypotheticals have, at the very least, crossed your mind. On March 24, the show’s second season continues the wild, subversive horror story of a varsity girls’ soccer team from New Jersey whose fantasies of championship glory meet a violent end when their plane to nationals crash-lands in the Canadian wilderness. (The show, which airs on Crave, was filmed in the gloomy forests of British Columbia.)

In a storyline that expertly mimics the timeless headspace of anyone touched by trauma, Yellowjackets pitches back and forth between the present-day lives of the survivors and the tragic events of 1996, a year once coincidentally dubbed “the year of the teenage girl” by the New York Times. Crucially, the show attempts, in nauseating detail, to make sense of the middle. How, in 19 months, could a group of superficially basic high school students devolve from Chuck Taylor–sporting athletes into dead-eyed, pelt-draped huntresses who cook and ritualistically consume their friend—or, maybe, friends? What makes Yellowjackets so compelling is how it circles a truth that’s simultaneously soothing and hard to digest: the fall into the recesses of our back brains is nowhere near as steep as we’d like to think. Any one of us could conjure our animalistic sides if pushed.

Husband-and-wife show creators Bart Nickerson and Ashley Lyle were smart to integrate this shadow delicately. In flashes forward, they charm with doe-eyed Melanie Lynskey (as the crafty Shauna Shipman) and disarm with Christina Ricci and Juliette Lewis, beloved princesses of darkness who deliver note-perfect performances as the brooding Natalie Scatorccio and wire-haired Misty Quigley, the team’s off-kilter equipment manager. Amid the maggot-foraging and a bacchanalian party that almost leads to human sacrifice, there are periodic moments of naïveté, as if to say, “See? They’re just kids!” There’s a fumbled attempt at virginity loss. There’s a rousing group dance-along to Montell Jordan’s “This Is How We Do It,” which, of course, blares from a Walkman. And even after Misty stoically performs a DIY amputation on their injured assistant coach, she reassures her teammates with her recognizable credentials. “I took the Red Cross babysitter training class—twice!” she says proudly. Then she disinfects the wound with Sea Breeze astringent, a retro teen skin care staple. True predators first make a point of putting you at ease.

Our pop-cultural fascination with murdery wilderness porn satisfies a collective need for disaster rehearsal. It allows us to ruminate on the worst of our impulses, and on our phobias, like plane crashes, rogue wolf attacks and finding oneself in the woods without a tampon. It’s also content that comes complete with a fun—if complicated—thought experiment: how do people behave when civilization is far but death is potentially very near? But more importantly: how would I behave—you know, in theory?

It makes absolute sense that a series like Yellowjackets, which debuted in November of 2021, was met with rabid binge-watchers, adoring critics and an impressive 100 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes. In real life, we were all the deepest we’d been into survival mode in quite a long while—two years into a pandemic that disrupted and overhauled our lives. We encountered the usual creep of climate calamity and wealth-hoarding billionaires, but also the very real risk that simply being breathed on by our loved ones could leave us seriously ill. Whether it’s Lost or Lord of the Flies—Yellowjackets’ most frequently cited comparison—art that acknowledges our mortality and wretchedness has often proved to be more entertaining in times of trouble than cheerier forms of escape.

Part of the inspiration for Yellowjackets’ plot isn’t fictional at all, which makes the show’s it-could-happen-to-anyone ethos all the more unsettling. The series draws from the story of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, which was hired to transport a team of young-adult rugby players from Montevideo, Uruguay, to a game in Santiago, Chile, in October of 1972. The plane’s right wing clipped a mountain in the Andes, resulting in a disastrous accident that left only 16 of its 45 passengers alive and stranded atop a mountain. Before the surviving players were rescued—and heralded as national heroes—they took turns punching each other’s feet to maintain circulation through the freezing mountain nights. One survivor even rationed a single peanut. After a week of frigid conditions and with their food supply completely depleted, some survivors ate their deceased teammates.

In the days immediately following the crash, the players’ innate coping strategies began to emerge: one temperamental survivor screamed at and stepped on his debilitated compatriots. Another, disabled by two broken legs, pitched in by studying maps to figure out the team’s location. True to form, the captain, Marcelo, delegated busywork—like finding unbloodied, drinkable snow—to keep everyone from focusing on their grim situation.

None of the Yellowjackets’ various wilderness personalities are huge surprises. Their dangerous new conditions only amplify less-than-savoury characteristics that already existed. What those girls get up to deep in the northern backcountry is a natural progression from their promise-filled existences in New Jersey—not an aberration. For those who think the teen-girl factor precludes Yellowjackets from ever achieving Lord of the Flies–levels of feral, I’d say: have you ever met or been a teenage girl? Yes, there are dorktastic singalongs and a certain aura of sweetness, but also weird rituals, ceremonial garb (friendship bracelets), tribalism and blood. What elevates the series from pure brutality to brilliance is its focus on creatures, easily mistaken as harmless, who conceal a sharp, ruthless edge. Kind of like their insect mascot. Kind of like actual human beings.

It’s pretty easy to imagine these suburban gals as your high school friends. Back in ’90s Jersey, our anti-heroines weren’t waging battles against the elements but each other, for social supremacy. The series’ first main-character kill-off involves being ostracized to death. The relationship between resident besties Shauna and Jackie, the team’s pretty, selfish captain, looks close at first but is riddled with jealousy and backstabbing. When things get properly violent, as in the case of single-minded Taissa Turner, it involves purposely splitting the shin of a weaker teammate to preserve her chance at championship gold—even if Taissa would never admit it. (She later runs for state senate.) Other players arrive in the forest knowing their way around a gun, or medicated for delusions. The show’s writers seem to suggest that even if we’re bummed out and bogged down by our id-based qualities, they might just come in handy later on. That’s the genius—of these so-called flaws and of the show itself.

Modern-day psychologists examine the nuances of survival behaviours, now viewing them less as unsightly brain grooves to be smoothed over and more as deeply intelligent mechanisms in the right circumstances. They may not be particularly virtuous, but they keep us alive. Yet when we see the day-to-day existences of the adult Yellowjackets—many of whom make it out of the Canadian brush without a discernible moral compass—we can understand how these same impulses can keep us from really living outside of life-or-death scenarios. The adult Yellowjackets cope in ways that are more relatable than cannibalism: Natalie struggles to stay clean after multiple trips to rehab, while Shauna finds outlets in adultery and some darkly funny jokes. (When she eventually kills her paramour, partially out of self-protection, she compares remembering how to dismember a body to “riding a really gross, fucked-up bike.”) As a teen, Taissa’s ruthlessness makes her most likely to succeed: she dreams of being first-string on Howard University’s soccer team, dating beautiful women and landing a legal internship in New York. “You did do all those things,” Shauna says, once they’re both adults. But Taissa, who has dissociative episodes and a young son in therapy, replies: “But if I’m being honest, not a single one of those things felt real.”

Heading into season two, old wounds don’t appear to be healing; somehow, things are getting much scarier. In fact, one teammate seems to be leading a cult. The show’s earliest cult, though, forms around the Yellowjackets themselves. At one point in the present-day timeline, the characters chafe their way through their 25-year high school reunion as they’re greeted with a winners’ welcome and a corny slideshow of memories set to Enya’s “Only Time.” It’s not always satisfying to celebrate survival tactics as evidence of the triumphant human spirit. Sometimes, what you need is to bond over shared scars and secrets with friends who have witnessed the full extent of your human shittiness. It’s nice to hear, “Wow, that was the worst.” Or, “We are kind of the worst.” Reflection over perfection. Television often does that very well.

Most of us will not find ourselves stranded on a mountain or in a forest. (Some of us may find ourselves in the domesticated wild a couple of hours north of a major city, but likely in the context of a cottage weekend.) Our most formidable personal disasters will probably be some form of heartbreak, financial ruin or remotely educating small children during a plague. To cope, we will do what we can, if not everything we want. We will not eat people; we will pay for Crave and find another form of catharsis. And we will try, as Natalie says during her last group-therapy session at rehab, to find a way to keep the tiger in the cage.