Fourth-quarter GDP growth was bad: here’s why

The Canadian economy needs a lift, but the world isn’t co-operating

Share

Update: As expected, GDP growth in the last quarter of 2012 was a dismal 0.6 per cent annualized, and the economy shrank 0.2 per cent in December. Despite that, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty said today the government might further trim spending in the next budget, as lower-than-expected growth impacts revenue flows the bean counters were banking on. NDP House leader Nathan Cullen called the finance minister’s concern over balance budgets at a time of withering growth “a manufactured crisis.”

Here we explain why the economy stalled in late 2012 and why it might take some time for it to pick up speed again.

—

Canada’s fourth-quarter GDP figures, out on Friday, are expected to show the clearest picture yet of the shift the economy has been undergoing for the per past year or so. For the first time in nearly seven years, monthly GDP numbers have already revealed, Canada underperformed the U.S. in 2012.

In January, the Bank of Canada forecast Octoober-to-December growth would come in at one per cent, but Governor Mark Carney hinted this week he expects the actual number to be lower.

Why the slowdown? Largely, because consumer spending and the housing market, which propelled Canada out of the recession as the rest of the global economy dwindled, are losing steam. And now that the economy can’t run on internal combustion alone anymore, it’s not clear how much of lift it’s going to get from the outside.

Here’s what happened over the past decade:

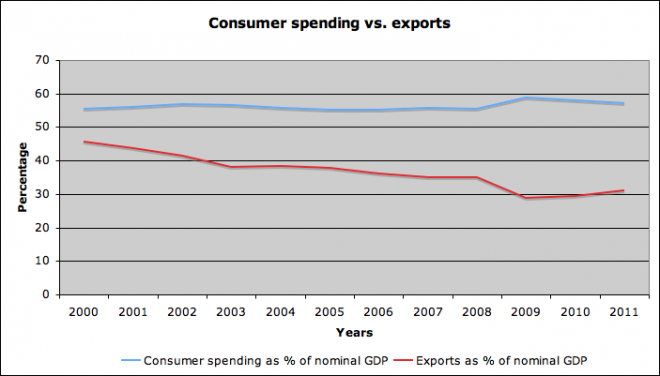

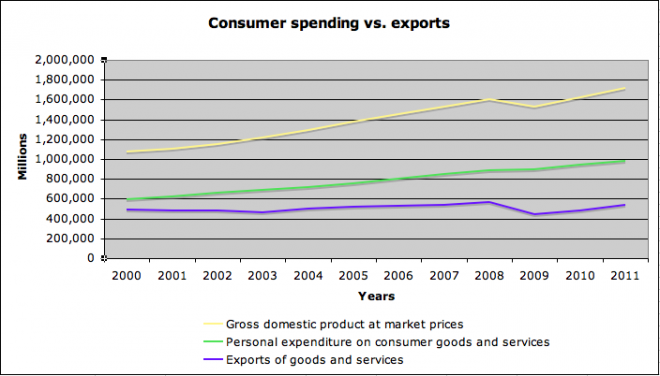

Exports, Canada’s traditional engine of growth, have been shrinking as a share of the economy: down to around 30 per cent of non-inflation adjusted GDP from a record 46 per cent in 2000. As the chart shows, the 2008-2009 crisis delivered a considerable blow to Canadian exports, which fell faster than GDP and haven’t come close to recovering. But the decline started long before global demand seized up in the wake of Lehman Brothers etc. The long-term trend reflects a loss of competitiveness and failure to diversify away from the U.S. and toward Asian economies, as the Bank of Canada has long been saying.

Consumer spending, by contrast, expanded as a share of the economy during the recession, limiting the magnitude of the contraction and picking up the slack from declining net trade:

Let’s take a look at residential real estate now. As Econowatch pointed out before, the housing sector has grown considerably as a share of GDP over the past decade:

The trouble now is that the housing market has been cooling since the middle of last year and indebted consumers seem to have finally (hopefully?) maxed-out.

What Ottawa and the BoC are banking on now is what might be called the “Great Canadian Back Swap:” exit real estate and households, and enter exports once again.

Too bad the rest of the world isn’t cooperating.

Take Washington’s sequester, for one. The $85 billion across-the-board spending cuts set to come into effect on Friday (barring another Hail Mary postponement) risk slowing down cross-border trade just as the U.S. recovery shows signs of picking up. U.S. authorities stand ready to ax some 2,750 border inspector jobs, which might clog airports and other key transit points, the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters organization warned. On the chopping board is also spending needed to implement the Canada-U.S. Beyond the Border Action Plan, which was supposed ease post-9/11 security and bureaucratic bottlenecks that Ottawa said cost the economy an estimated $16 billion a year.

And there’s more bad news from Europe, where Italy’s inconclusive elections might open yet a new chapter in the euro zone crisis. Though the Old Continent isn’t one of Canada’s chief trade partners, a deeper recession there would still hit Canuck exports, albeit indirectly.

So, what if exports fail do to the heavy lifting? In a speech on Monday, Canada’s central banker spoke hopefully of timid increases in corporate borrowing, which, if sustained, might mean more spending on things like machinery and equipment.

Alas, though, as the Wall Street Journal notes, today’s Statistics Canada survey on business investment intentions might have muted even the governor’s resilient optimism. Public and private firms polled by the statistical agency said they expected investment to inch up a meagre 1.7 per cent in 2013, the smallest gain since 2009.

Of course, what investors say they’ll do and what they actually do aren’t always the same thing. And business moods would likely turn quickly, if the dark clouds abroad somehow dissipate — say Washington avoids the sequester and shelves the meat cleaver approach to budget cuts and the euro zone manages once again to hold itself together.

That, though, is a very big “if.”