Really bad bosses

Visionary leaders get a pass for bad behaviour. For the rest, toughness is falling out of favour.

Emmanuel Dunand / AFP / Getty Images

Share

The late Steve Jobs left a lasting mark on the world of consumer electronics. He also left a bruise on many of his employees.

As the driving force behind Apple’s iEverything years, Jobs oversaw the launch of a string of game-changing products—the iPod, iPhone, and iPad—that left rivals like BlackBerry and Microsoft in the dust. But despite being a true visionary, Jobs could also be a horrible person to work for. In his authorized biography of the Apple co-founder, author Walter Isaacson describes several instances of Jobs flying off the handle at employees who failed to meet his often impossible expectations. Following the muddled rollout of Apple’s MobileMe cloud synchronization service, Jobs gathered the team responsible in a board room. “Can anyone tell me what MobileMe is supposed to do?” Jobs asked. After listening carefully to their responses, he narrowed his eyes and demanded, “Then why the f–k doesn’t it do that?” The team’s leader was fired on the spot.

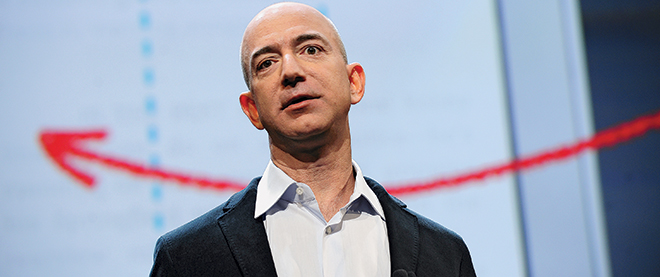

Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon, is another Silicon Valley heavyweight whose single-minded focus can make employees quiver. According to Brad Stone’s The Everything Store, Bezos has been known to cut down senior managers with quips like, “Are you lazy or just incompetent?” He also forwards customer complaints to employees with nothing more than a menacing question mark attached. Canada, too, has had its share of tough bosses. Cable magnate Ted Rogers, though perhaps better known for his colourful language (he once called rival Bell a “Soviet-style” monopoly), was also famous for wearing out senior Rogers Communications executives with his 24-7 work ethic and penchant for phone calls at odd hours.

Given the stellar success of such individuals, it’s tempting to conclude that difficult bosses make great companies. But experts say people like Jobs were probably successful in spite of their questionable people skills, rather than because of them. “Steve Jobs just had a great track record, so what can you say?” asks Karl Moore, a business professor at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management. “We tend to cut those people more slack because they’re geniuses and we’re not.” So what does make a great boss? Increasingly, it’s an ability to deliver results by teasing the very best out of employees—without screaming at them.

Several recent studies suggest that bad bosses are responsible for most employee dissatisfaction at work. A 2011 study led by Accenture found that the top reasons employees left their jobs included: a lack of recognition, internal politics, a lack of empowerment and simply not liking their boss. In 2012, PricewaterhouseCoopers asked 19,000 people who had recently left their jobs why they decided to quit. Five of the top 10 reasons also had to do with poor supervisors, including bosses who played favourites, showed poor leadership skills or failed to provide employees with the necessary support. “The old saying, which is still true, is that people quit bosses, not organizations,” says Robert Sutton, a professor at Stanford University and author of several books about innovation and management, including Good Boss, Bad Boss.

There have also been clear links drawn between likeable bosses and financial performance. A 2002 study by the Gallup Organization looked at 36 companies and found that, as employee satisfaction with their jobs increased, so did measures like customer satisfaction, productivity and profit. Meanwhile, levels of employee turnover fell, as did workplace accidents. “One implication is that changes in management practices that increase employee satisfaction may increase business-unit outcomes, including profit,” according to the researchers. Another study by Mercer found that the most important factor that analysts consider when recommending a stock is the quality of the management team. In other words, good bosses matter.

Moreover, it’s not just the person at the top who’s important, but the various layers of management throughout any large organization. Sutton cites Google as a company that has gone to great lengths to improve the quality of its management teams at every level. Whereas the search giant once promoted its brightest engineers into management positions, it now focuses more on people who are good at listening to employees and helping them work through challenging problems. In typical Google fashion, the new approach was adopted after crunching a huge amount of data about employee engagement that found technical expertise was actually among the least important qualities when it came to motivating workers. “They’ve discovered that, when they don’t have skilled managers—and that’s not just technically skilled, but emotionally skilled as well—their best people leave, and they don’t want that,” Sutton says.

With so much evidence pointing to the need for quality management, why are so many corporations seemingly rife with bad bosses? Sutton attributes it to the lingering effects of a more old-fashioned way of doing business—one that favours military metaphors like “marketing blitzes” and “boardroom coups,” and puts more emphasis on results than people. “There’s still a lot of companies that focus on the money too much, and there’s some evidence that they tend to drive out some of the talented folks,” Sutton says. The zenith of the era may have been reached with “turnaround specialist” Al Dunlap, who earned the nickname “Chainsaw Al” after relentlessly downsizing a number of corporations in pursuit of bigger profits. He was ultimately fired as CEO of appliance-maker Sunbeam in 1998 and was subsequently charged with fraud. He eventually settled with regulators for $500,000 and agreed to never run another public company.

The good news for cowering employees is the old attitudes are disappearing. The buzzword in most corporations these days is “innovation”—the idea that companies should be constantly trying to raise the bar when it comes to developing new products and services. But since most corporations aren’t blessed with a Jobs- or Bezos-like visionary at the helm (or cursed, depending on what kind of mood they’re in), companies are usually forced to rely on their most valuable assets for new ideas: employees. “It’s not just about the five-year plan, but learning as we go along, and that doesn’t just come from one person,” says Moore. “You’re looking more for senior executives who will listen and pay more attention to what junior people say. Their job is not to have good ideas, but to recognize them.” And, increasingly, that means using a mesh-backed Aeron office chair to sit down and have a conversation—not hurl it against the wall.