Why the death of Vine is about more than just the end of an app

People of colour embraced Vine. But when corporate parent Twitter chose bullies over those who made its platform work, they left.

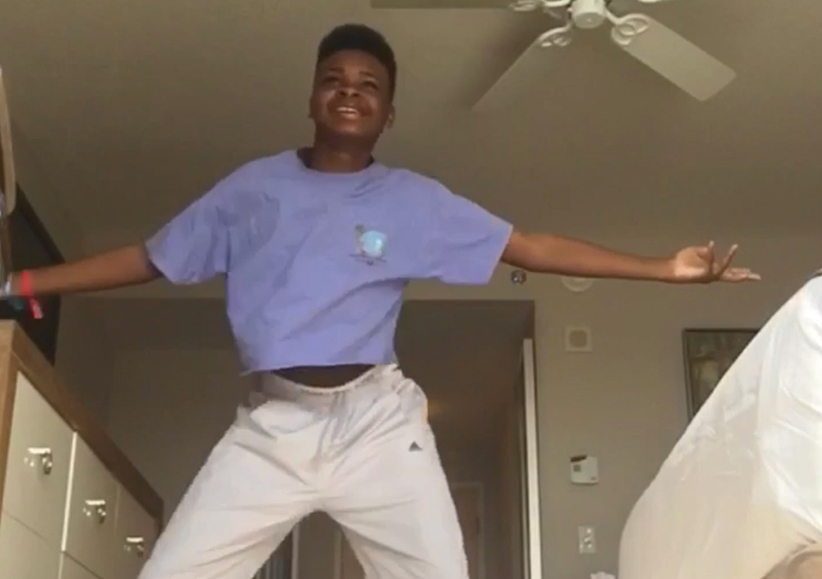

(Jay Versace/Vine)

Share

Last week, Twitter announced the end of Vine. If you’re not familiar, Vine was the video equivalent to Twitter’s 140-character microblogging service: users were allotted six seconds to make a statement. While Twitter originally advertised the platform with stop-motion home videos and twee music—think of your best friend’s Pinterest page set to Belle and Sebastian—what emerged was something its creators never envisioned. Amateur comedians, dancers, and video magicians became massively popular on Vine, drawing millions of followers and billions of views. But a massive drop-off in viewership over the past year, coupled with Twitter’s failed attempt at selling itself to the highest bidder, led to Vine’s early demise. While the announcement may come across as a sad end to a popular experiment, it’s actually indicative of two new realities in the digital age: That audiences and content creators of colour are to be ignored at one’s own peril, and that some tech companies will blithely choose peril.

Vine’s widespread appeal came from its radical simplicity and its cultural in-jokes. Fancy, professional production was not only unnecessary, it was to be avoided: some of the most popular Vine creators were teenagers filming at home and around the neighbourhood. Those creators who popularized the six-second sketch, for the most part, were people of colour. In Black households, “do more with less” is less a work ethic than a means of survival, but on Vine, it was a business plan. Creators like Jay Versace, a lanky, round-faced high-schooler, produced hilarious videos lampooning R&B music and shady relatives with little more than improvised wigs and his rubber-faced lip-synching. Dance “challenges” like the “Whip/Nae Nae” and “Betcha Can’t Do It” have exploded on the platform, offering exposure to professional creators who blend talent with goofy wit.

Unlike Twitter, where viral tweets offered hardly more than a few days’ visibility, exposure on Vine had the ability to launch careers. In August 2014, U.S.-based actor Greg Davis Jr. (known on Vine as “Klarity”) posted a video of himself overlooking the canals in Venice, Italy. The loop was set to Jay-Z’s “F–k With Me You Know I Got It,” with late rapper Pimp C’s opening monologue:

“Little over a year ago I was in bondage

And now I’m back out here reaping the blessings

And getting the benefits that go along with it”

In his post, Davis connected the words to his own life—a year prior, he was homeless, had difficulty landing roles and his father had just passed away. But his Vine comedy shorts helped him amass more than two million followers—more than Miley Cyrus—and that following has more than doubled since. Davis joined the ranks of Vine’s top stars and not only found more work, but managed to draw a six-figure salary once his videos caught the attention of corporate sponsors like Coca-Cola and Charmin. Davis kept producing Vine videos until the very end, but most of his peers had long since abandoned the platform for rivals YouTube, Instagram and Snapchat. Those services not only offered creators more flexibility, exposure, and revenue-sharing, but also addressed a problem that has plagued Twitter for years: shielding users and creators from online abuse.

Before the trolls temporarily drove Ghostbusters star Leslie Jones away from Twitter, the free speech ethos of its white, male executive team had become something of a running gag. In their eyes, adding features to prevent online bullies from exercising harassment (and even rape and death threats) interfered with their vision of an online ecosystem where all voices were equally heard. And yet, when media giants like the NFL demanded tweets be taken down due to copyright infringement, those tweets disappeared quickly. It was clear whose voices mattered to Twitter’s executive team.

Former Twitter CEO Dick Costolo famously admitted in 2015, “We suck at dealing with abuse.” Since then, however, the company offered barely more than half-measures (such as its “mute” feature) and occasional account terminations (Such as alt-right apparatchik Milo Yiannopoulos, who orchestrated the abuse directed toward Leslie Jones), which did little to stem the flood. The executive team’s unwillingness to offer more protection, in favour of allowing bullies and actual neo-Nazis free reign to harass everyone from celebrities and journalists to casual users, caused potential buyers Google, Disney, and Salesforce to pass on acquisition bids. In mid-October, Bloomberg reported Disney executives were worried “bullying and other uncivil forms of communication on the social media site might soil the company’s wholesome family image.”

This was a concern that Vine’s most popular creators brought to the company’s attention earlier this year. In a closed-door meeting, 21 Vine creators (who were responsible for billions of annual views) asked for payment in exchange for regular content creation. Additionally, they asked for product changes, namely protection from online harassment. Vine rejected the proposal, and the creators took their work to other platforms. While Vine did eventually produce content filters to reduce harassment, by then it was too late. The talent had left the building, viewership had plummeted, and advertisers had no incentive to help the company monetize. After the failed sale, Twitter axed nine per cent of its global workforce and shut down Vine for good.

It’s sad to see Vine go. There were times when its funny, adorable, and socially incisive videos could make me laugh in spite of otherwise terrible days. At the same time, there’s something revolutionary about the fact that creators of colour were able to walk away intact from all this. Especially from a corporate giant that chose bullies and contradictory principles over the people who made its platform work. After decades of Black and brown entertainers being exploited, held hostage to unconscionable contracts, and left penniless when their 15 minutes ended, it’s a complete reversal that Vine’s talent walked away while the company collapses. While Vine’s management bears a wider responsibility for failing to adapt its product to the way its users actually consume the product, there’s still a point to be made for the wider tech community. Millennials of colour are the ones who create and sustain culture on the Internet. Catering to that market is good business sense. Cross them and, well, your company might just die on the vine too.