Canada’s housing bubble makes America’s look tiny

Comparing Canada’s infatuation with real estate against the peak of the U.S. housing bubble yields some disturbing insights

From afar, Calgary real estate may be looking like a good buy

Share

It’s been just over a decade since the U.S. housing market peaked, and rarely a day goes by without stories exploring the hot real estate market in Canada. Whether it’s warnings about elevated levels of household debt, government regulations to cool prices or the influx of foreign money, residential real estate generates sustained discussion and debate. After witnessing the housing crash south of the border, and the carnage it wrought, this is to be expected.

For all the attention, it’s notable that most analysts don’t see Canada facing a U.S.-style housing crash. For instance, Moody’s Analytics argued this month that even though price growth will decelerate, there is not likely to be a hard landing. Some observers are a bit more pessimistic, such as TD Bank, which predicts a 10 per cent fall in Vancouver house prices. Still, if there is a consensus view among professional forecasters about the Canadian housing market, it’s that prices will plateau or suffer only a minor dip. For a variety of reasons, most people do not see a U.S.-style crash on the horizon for Canada.

Yet when it comes to our respective housing bubbles, comparing Canada’s current infatuation with real estate with the peak of property mania in the U.S. yields some disturbing insights. We may not be as different as we like to think.

When looking at housing markets, the most obvious comparison is price. How does the level and trajectory of Canadian house prices stack up against the U.S.?

The following chart is drawn from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’s International House Price Database. It’s an index (100 = prices in 2005) of real, or inflation-adjusted house prices, and it drives home just how much more inflated Canadian house prices are than at the U.S. bubble’s peak. The chart also includes Japan and its mammoth housing bubble of the 1980s—which is more akin to what’s gone on in Canada.

Here’s another way to look at the astonishing price gap between Canada now and when the U.S. bubble peaked. BMO economist Sal Guatieri put together the following chart in May, showing average house prices for Canada and the U.S. since the year 2000 but with both housing markets denominated in U.S. dollars in order to show relative valuations. It reveals just how expensive our housing market has become relative to the U.S. bubble’s peak.

As has been pointed out many times, two cities in particular are driving Canada’s real estate boom: Vancouver and Toronto. Here are how those two cities compare against four American cities that saw rapid house inflation during the U.S. boom. Vancouver’s market quite clearly leads the pack, with prices going parabolic. Toronto comes in second, with its price appreciation since 1998 eclipsing the mid-2000 bubbles in all four American cities on the graph—even the hyper-charged markets of Miami and Las Vegas.

Of course, prices are not the only way to look at the evolution of a housing market. Another important consideration is the level and change in household debt. As with the U.S. bubble, a surge in household indebtedness (principally via mortgages) has provided the fuel to send prices soaring. If we examine U.S. and Canadian household debt-to-GDP ratios, we see that Canada recently exceeded the level reached by American households in the first quarter of 2008.

Perhaps a more telling comparison, however, is household debt to disposable income for the two countries. Indeed, that’s the ratio more often cited by economists, because it measures the debt burden of households against the income they have available to repay it. When Canada’s debt and income data is adjusted to reflect how the U.S. measures them, Canada’s debt-to-income ratio now sits just shy of the U.S. peak reached in the wake of the housing crash. (It should be noted, though, that among industrialized countries, Canada is not the most indebted using this ratio. Norway and the Netherlands have household debt to disposable income ratios well in excess of 200 per cent, while Denmark’s households owe just over 300 per cent.)

Some critics have in the past argued that household debt to disposable income is a misleading metric, when what really matters is not the debt burned itself but the ability of households to manage it. And for a long time, Statistics Canada’s debt-service ratio—the amount of disposable income required to cover debt payments—showed Canadian households in a far better position than American households were at the time of the housing crash, with Canada’s ratio hitting record lows thanks to near-zero interest rates. But those claims were made when StatsCan only published the interest part of debt servicing. Now that StatsCan includes principal repayment in the calculation, bringing the measure in line with the U.S. methodology, the situation in Canada looks much grimmer and skeptics have stopped using it.

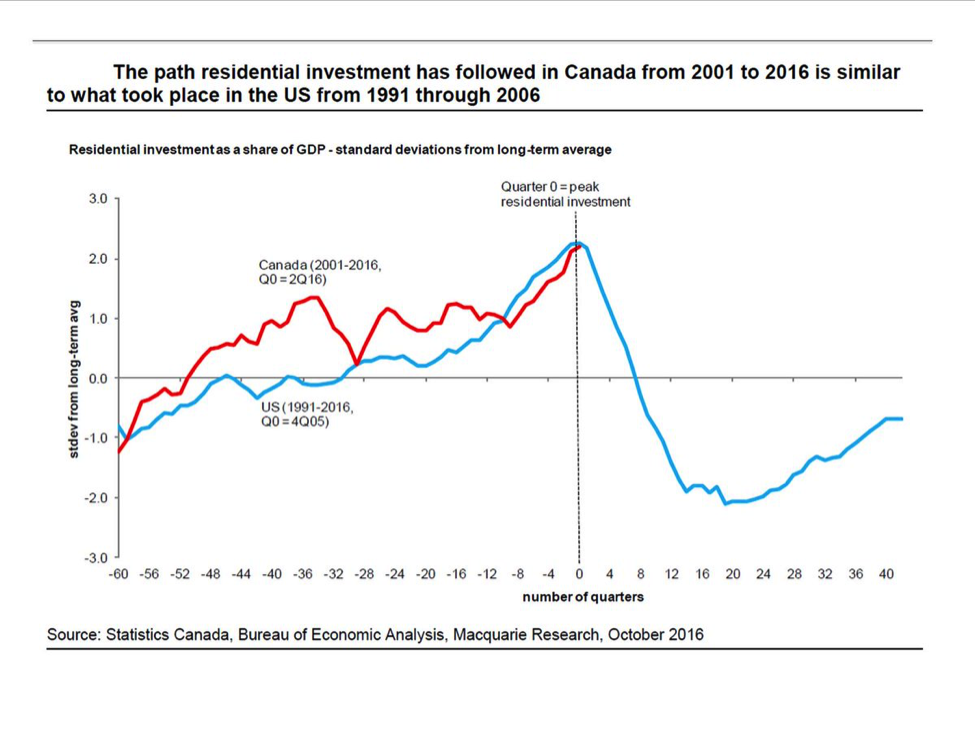

Another way to assess a housing market is to consider it relative to the size of the national economy. Again, both in the case of the U.S. at the time of the bubble and in Canada now, residential construction represents a sizable share of GDP. Further, the following graph from investment bank Macquarie suggests that Canada is following the path of the U.S. when it comes to this sector. And crucially, using the U.S. bubble as a guide, Canadian residential investment may have recently peaked.

Comparing the underlying data and trends in the two North American housing manias is interesting. But it’s in some of the softer, less quantifiable aspects of the Canadian bubble that we see echoes of the U.S. boom.

Comparing the underlying data and trends in the two North American housing manias is interesting. But it’s in some of the softer, less quantifiable aspects of the Canadian bubble that we see echoes of the U.S. boom.

One obvious similarity between the Canadian and U.S. bubbles is the wall-to-wall coverage of all things real estate. Turn on Canadian radio and television these days, or browse the Internet and social media, and you’ll encounter a near-constant barrage of pitches for condos, mortgages (as well as second mortgages) and real estate seminars, promising the secrets of easy real estate riches as taught by self-professed experts. Also ubiquitous: ads for debt management and credit counselling.

As with the U.S., too, there are seemingly compelling arguments put forth as to why bubble fears are overblown. For example, in 2004, then-Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan argued that U.S. households were actually in reasonably good shape, despite rising consumer debts. In painting a healthy picture, Greenspan pointed to rising household net worth, which of course was principally the result of the soaring real estate market. The problem was, when the market crashed, so too did the net worth of U.S. households. Similar arguments have been repeatedly made in Canada.

Given all these similarities, both statistical and anecdotal, why then do more people not believe Canada could suffer the sort of housing crash that the U.S. suffered?

In part, it may be related to how the respective bubbles formed. The U.S. bubble involved widespread use of complex products such as collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps. That sort of financial engineering is not nearly as prevalent in Canada, and while there are signs of fraud in the mortgage industry, the causes of the Canadian bubble seem more straightforward: low interest rates and lots of bank lending (much of it insured by the taxpayer), with foreign investors also playing a role in certain areas (namely Vancouver). Oh, and old-fashioned greed, fuelled by ridiculously unrealistic expectations.

Another explanation for the lack of housing fear lies in Canada’s sense of its own economic exceptionalism. When the U.S. housing market collapsed, it kneecapped the global economy, and yet Canada emerged largely unscathed, with observers praising the health of Canada’s banks. Then when the European debt crisis and U.S. debt ceiling debates raged, observers again pointed to Canada for its sound government finances. Now as global growth slows, yet more observers are singing Canada’s praise for its embrace of fiscal stimulus, trade and newcomers, a stark contrast to the presidential candidacy of Donald Trump. It’s enough to make anyone smug.

Canada better hope all this housing confidence is justified. If there’s one thing the U.S. crash reminded us, it’s that housing bubbles can have very serious and long-lasting consequences—property values crater, mortgages become millstones, consumer spending plummets, and unemployment soars.

After all, with so many indicators suggesting Canada’s housing market has inflated well beyond what the U.S. experienced in the early 2000s, this chart showing what America’s 33 per cent house price decline would mean for the Canadian market is sobering.

But surely that can’t happen here. Right?

With files from Jason Kirby