Change and pain are headed for Canada’s housing market

As Ottawa moves to cool the excesses of the housing market, those who’ve benefited from the bubble should hope for the best, but expect the worst

People walk past new homes that are for sale in Oakville, Ont. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nathan Denette

Share

Earlier this month Canada’s Finance Minister Bill Morneau unleashed a three-pronged attack on the housing bubble in Canada. These measures are substantial. If successful, they will improve tax fairness, introduce risk-sharing for lenders and restrain runaway house price inflation in Toronto and Vancouver. But significant collateral damage seems inevitable as these changes strike at the heart of the factors that are driving the housing industry.

The change in tax rules targets some speculators who’ve been trading Vancouver and Toronto properties like penny stocks while not paying taxes on their gains. How many of these speculators, foreign and domestic, would qualify for the principal residence exemption isn’t known, as most don’t bother reporting to the CRA when the property is sold. But the new rules require that sales are reported on Canadian tax returns, whether tax is owing or not. If Vancouver real estate has been used for money laundering on a global scale, as many newspaper reports suggest, this new stance by the authorities might bring an abrupt halt to the “hot money” inflow, an important source of funds for very expensive housing. House prices could fall precipitously, since the tax change comes right on the heels of the new 15 percent foreign buyer tax on property transfers in the Vancouver area.

The second initiative, the mortgage-rate stress test, modifies how home buyers qualify for high-ratio loans (more than 80 percent loan-to-value). Until now, with interest rates at all-time lows, it’s been possible for first-time buyers to qualify for large loans, even with modest income. The housing bubble expansion depends on lenders uttering those magic words, “You’re approved,” every single day in many cities and towns across Canada to first-time buyers, as they are an important source of new money.

After October 17 Canadians might find a much cooler reception at the mortgage store. The change means that insured mortgages must be tested at the banks’ five-year posted rate, currently 4.64 percent. Hundreds of thousands of buyers could be affected as the qualifying rate was as low as 2.17 percent until now. For a household with $100,000 in total income the stress test could mean a 20 percent drop in approved mortgage value.

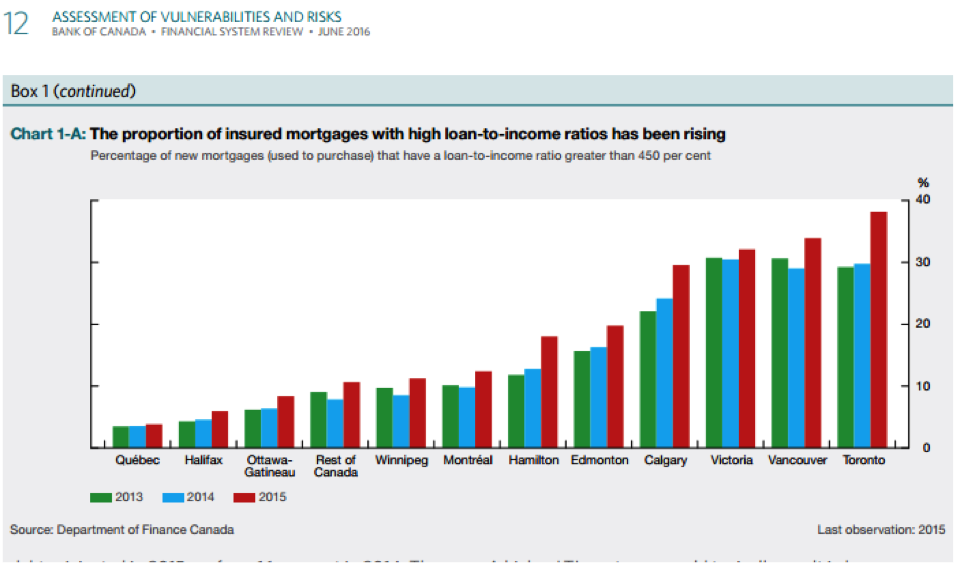

The impact will be substantial, based on comments from lenders. The Bank of Canada estimated that more than 20 percent of all insured mortgages were contracted by households that have loan-to-income ratios of more than 450 percent.

Home buyers in Vancouver, Toronto, Victoria, Calgary and Edmonton are at the head of this class of risky borrowers. The slowdown in new money from this second source of buying power will have a large impact, especially on new home builders in those centres.

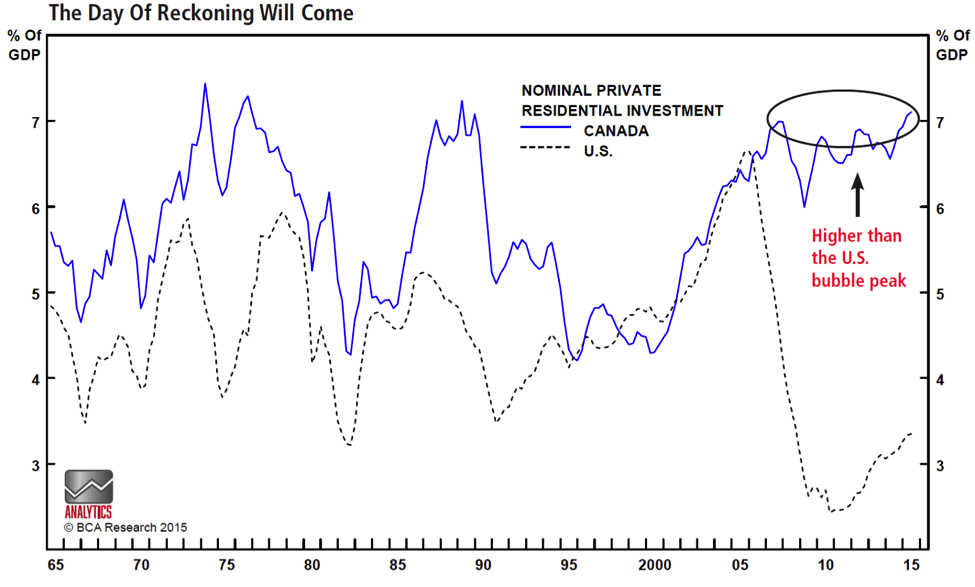

Both initiatives are potentially devastating to one of the most important industries in Canada. Along with energy and manufacturing, residential real estate is a key growth factor in the Canadian economy. Home builders, construction workers, realtors, renovators, architects, banks, non-bank lenders, shadow bank lenders, lawyers, notaries, building product suppliers, furniture stores, electricians, plumbers, land speculators, carpenters, high-rise condo developers, advertiser-dependent media, provincial governments, municipalities and many others count on housing-related activity to keep the cash register ringing.

Here’s the direct residential investment portion compared to the U.S.:

The third initiative announced last week was more of a warning than a change, but the government appears determined to tackle this controversial issue. The idea of sharing the risk on insured mortgage debt between lenders and taxpayers has been floated publicly before, but nothing’s been done yet. Here’s Evan Siddall, CEO of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, speaking with Bloomberg’s Katia Dmitrieva on Oct. 4.

“Mortgage loan insurance is on 100 per cent of the loss, so we—us, Genworth and Canada Guaranty—insure all of that loss,” Siddall said, referring to CMHC’s two main private-sector competitors. “And lenders have, as I’ve said in the past, no skin in the game and therefore the incentives are misaligned with good risk management.”

Mr. Siddall was referring to a scheme that socializes, to the taxpayer, the impact of large potential losses on more than half of the total mortgage debt outstanding. Lenders can offer credit to Canadian homebuyers, on generous terms while collecting impressive profits, while taking very little risk and avoiding future losses.

This system is unique in the world. Basically it transforms high-ratio mortgages into Triple-A credit debt, equivalent to the safest government bonds. If lenders had been required to carry all risks associated with default on these loans, the amount of mortgage credit outstanding would be a modest fraction of what it is today.

Any serious attempt to change the rules around insured mortgages could roil share prices of publicly-listed Canadian lenders as well as disrupt financing for housing. The availability of mortgage credit could dry up and conditions would be much more difficult for many buyers. The federal government realizes the importance of this industry to lenders, business and households, so expect that adjustments will be evolutionary, without abrupt or radical changes. But the clock is ticking as international agencies are taking note of Canada’s unique situation which appears to be out of step with the rest of the developed world.

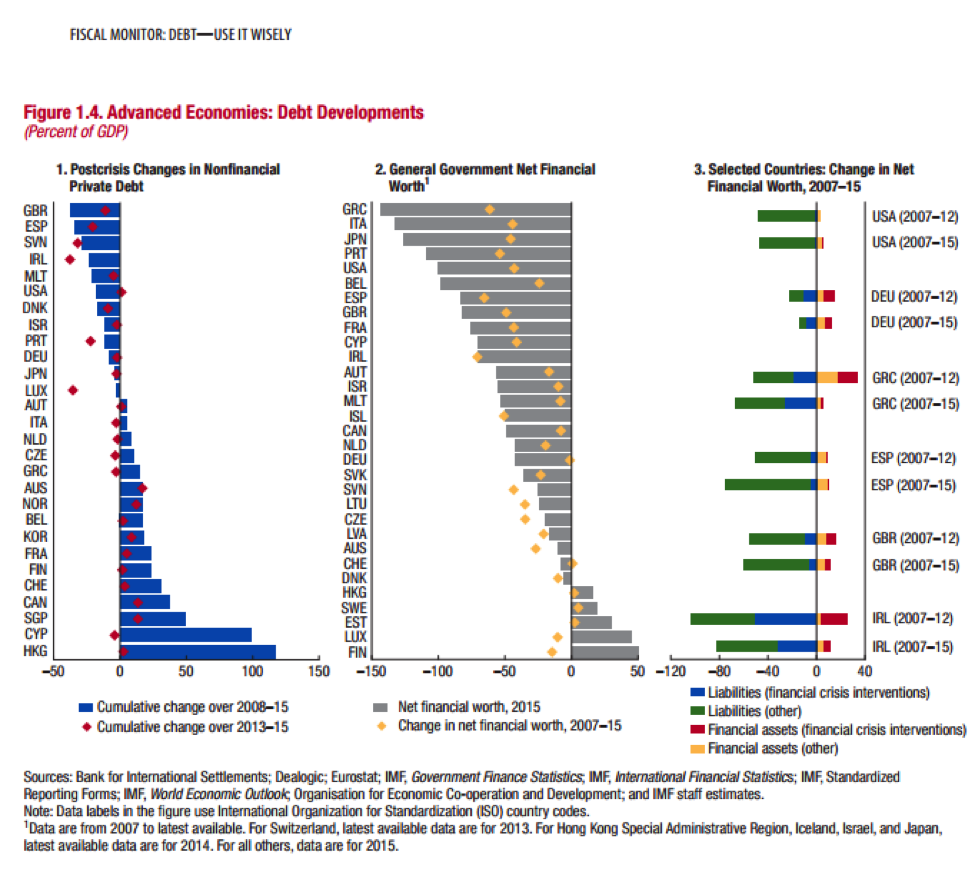

The IMF, in its Fiscal Monitor for October 2016, singled out Canada, along with Singapore and Australia as experiencing the fastest-growing private sector credit since the global financial crisis. About one-half of Canadian non-financial private sector debt is incurred by households, while the other half is business and corporate debt.

Most household debt is mortgage debt—71 percent of the total—so any attempt to slow credit growth must hit mortgage borrowing and the housing industry. The above chart shows the approximately 40 percent increase in private debt since 2008 for Canada.

All Canadians should support the Finance Minister in his attempt to make these bold changes. His adjustments to the rules could engender an orderly transition to a more balanced system and soft landing for house prices. But, while hoping for the best, Canadians would be wise to prepare for something worse than the oft-touted transition to stability. A painful unwinding of elevated leverage in the Canadian financial system is the most likely outcome, based on observation of similar adjustments in the U.S., Ireland and Spain.

The good news is that the federal government still carries a triple-A credit rating and a relatively modest ratio of debt-to-GDP. The government has the financial resources to step in, if needed, to help buffer the inevitable fallout from the unwinding of the biggest private sector debt bubble in Canadian history. Taxpayers won’t like it, of course, if they are required to recapitalize the CMHC and some of the weaker lenders, but the system will survive.

In exchange for their involuntary financial contribution, Canadians should demand that the rules be changed permanently so that the financial system can never get so far out of balance again.

As the saying goes, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

Hilliard MacBeth is the author of “When the Bubble Bursts: Surviving the Canadian Real Estate Crash”. He lives in Edmonton, Alberta.