Don’t look now, Canada’s economy is getting ugly

There’s been a lot of terrible economic news in recent weeks. At what point does this become a problem for Justin Trudeau?

Box turtle hiding in his shell on a white background. (Princessdlaf/Getty Images)

Share

Oooph. That’s about the best way to sum up the state of Canada’s economy after a barrage of awful economic reports in recent weeks.

First up was fresh evidence that Canada’s manufacturing sector is struggling, despite all the support it’s received from cheap oil, the low loonie and a strengthening U.S. economy. Factory sales fell in May by 1 per cent, the third monthly drop this year.

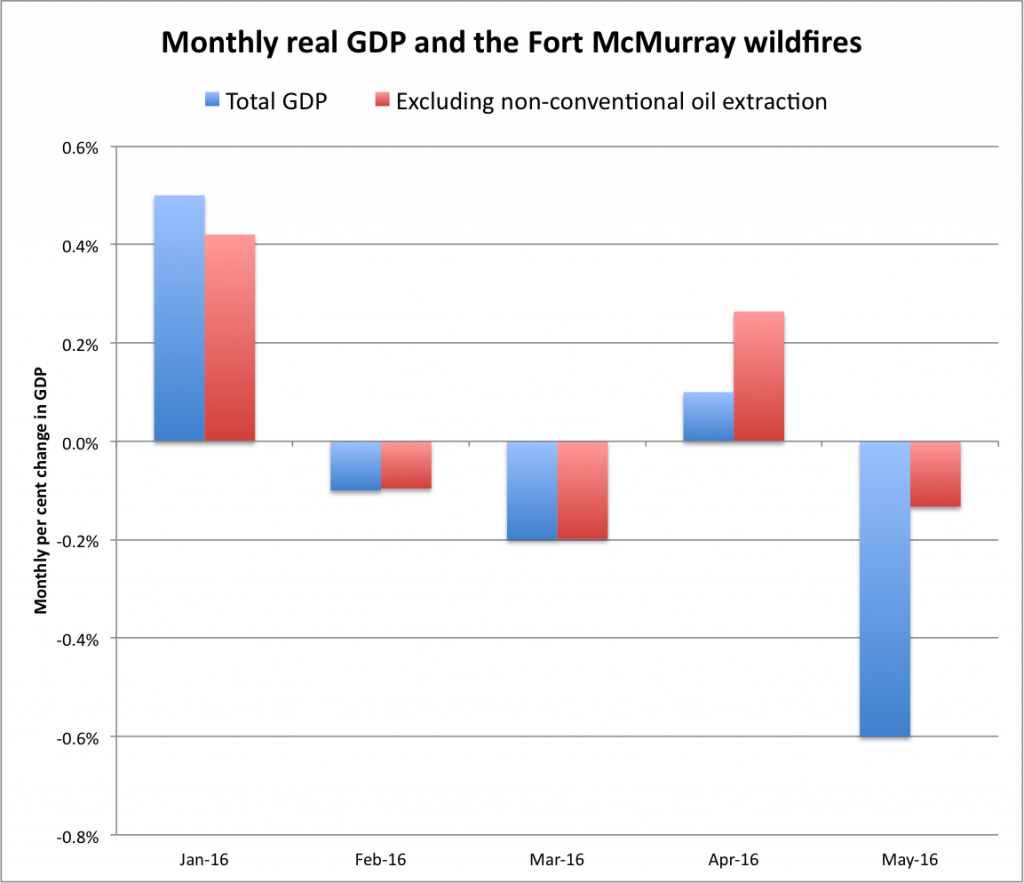

After that, we learned Canada suffered the steepest monthly decline in GDP since 2009, as the full impact of the Fort McMurray wildfires caused the economy to shrink by 0.6 per cent in May. As Statistics Canada noted at the time, the majority of the downturn was due to the fires, but not all of it. In fact, in three of the first five months of 2016 that we have data for, Canadian real GDP declined on a monthly basis, even when the beleaguered oil sands are taken out of the picture.

Then on Friday we got a double whammy of awful news on the jobs and exports fronts. First, the wallop from Statistics Canada’s labour force survey—the country lost 31,000 in July, a far, far cry from the 10,000 new jobs that were expected to be created. Ontario in particular was hit hard, losing more than 36,000 positions.

Then on Friday we got a double whammy of awful news on the jobs and exports fronts. First, the wallop from Statistics Canada’s labour force survey—the country lost 31,000 in July, a far, far cry from the 10,000 new jobs that were expected to be created. Ontario in particular was hit hard, losing more than 36,000 positions.

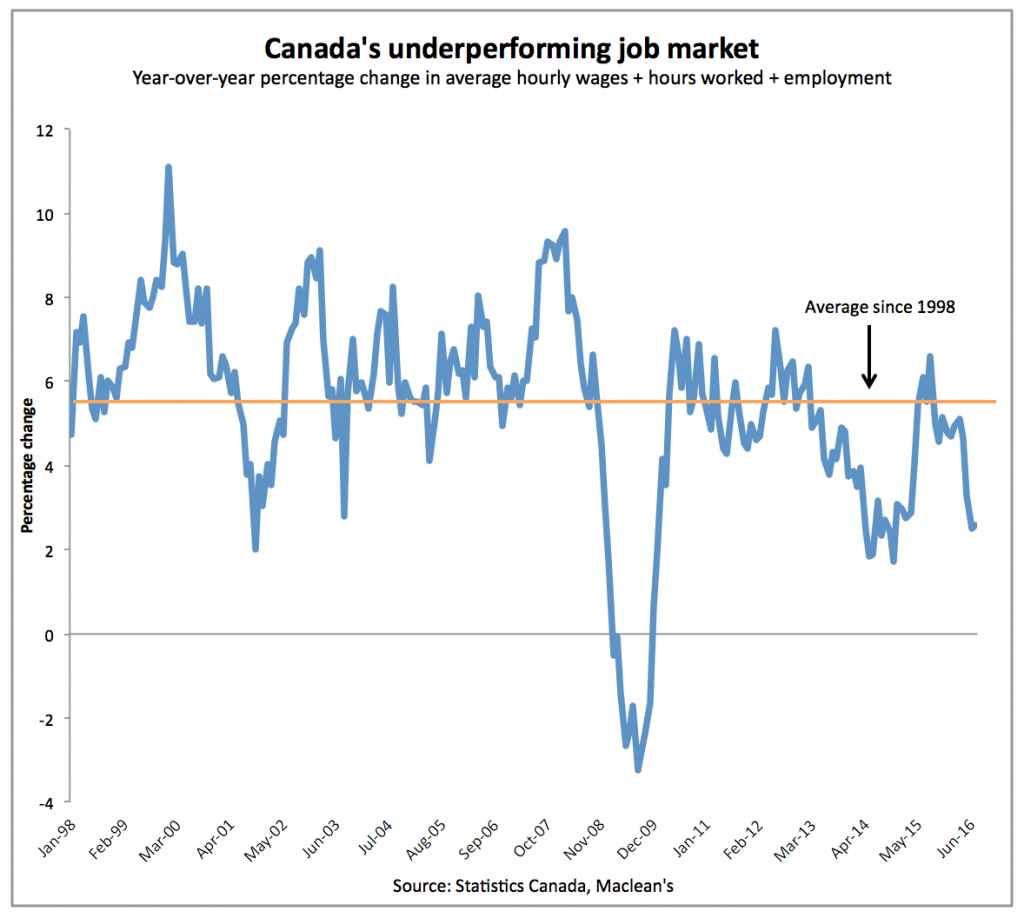

Perhaps one of the most troubling aspects of the jobs report, though, was that hourly wage growth has hit a wall, climbing just 1.8 per cent over last year, compared to an annual gain of 3.25 per cent in February. When combined together the drop in employment, slumping wage gains and stagnant growth in hours worked paint a picture of a labour market in distress.

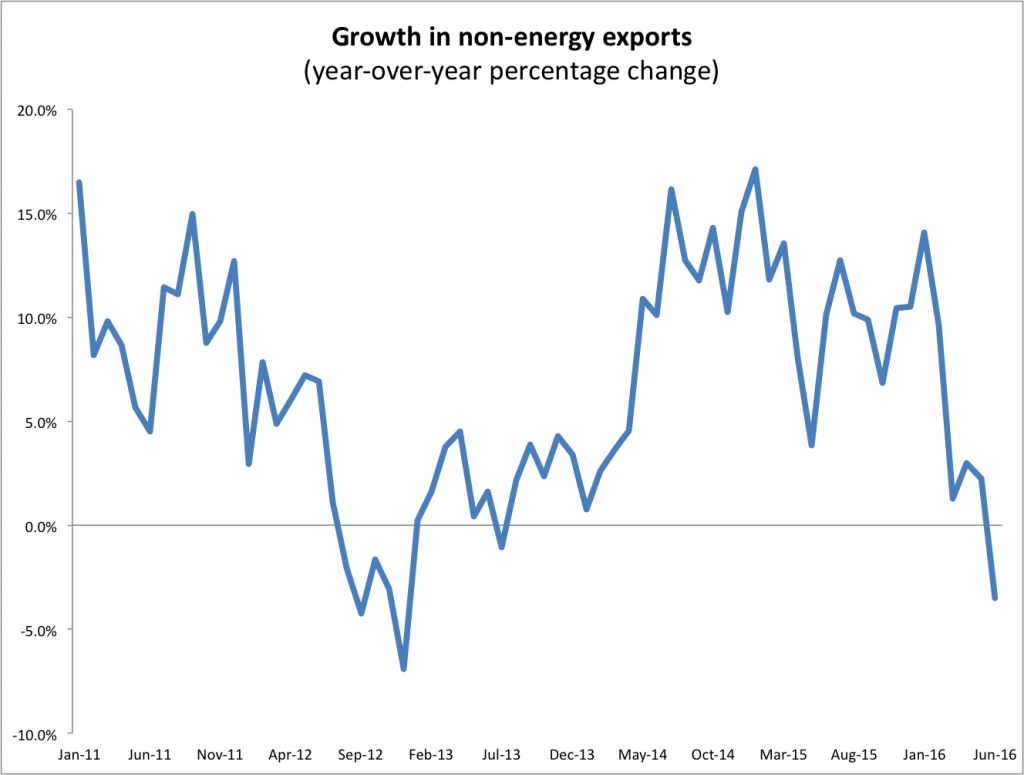

Friday also brought yet more dismal news about trade. Canada’s trade deficit—the gap between the value of the goods it buys from the rest of the world and what it sells—widened to its largest in history. The trade shortfall hit a record $3.6 billion in June—in fact, of Canada’s 10 largest monthly trade deficits of all time, five have occurred this year alone. Worst of all, non-energy exports suffered a fifth straight monthly decline, and fell 3.5 per cent from the year before, the biggest year-over-year decline since 2012.

That’s a lot of scary news for the economy to digest in a short period of time. The worry is this will create a feedback loop, where bad news begets more bad news. As it is, this has already been the weakest recovery for business investment in decades, with the private sector on track for its lowest share of capital construction expenditures in a quarter century. So it’s hard to see businesses opening up their wallets to invest, which is what’s sorely needed in order to reduce the economy’s over-reliance on consumer spending and real estate.

This is also likely to make the job of Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz a lot more difficult. The recovery in non-energy exports, driven by the weaker loonie and a strengthening U.S. economy, was an important part of his explanation for how Canada would finally move beyond the effects of low oil prices. At the very least, that recovery seems to be on hold, though perhaps continued improvements south of the border—a report on Friday showed the U.S. economy created 255,000 jobs, exceeding expectations of 180,000 new jobs—will boost Canada’s non-resource economy in the coming months. If that doesn’t happen, Poloz may feel he has to cut interest rates again, at the risk of further inflating housing bubbles in Toronto and Vancouver.

Before Poloz does that, though, he will want to see if the fiscal stimulus measures revealed in the Trudeau government’s first budget work as promised. Ottawa plans to run a $29-billion deficit in fiscal 2016-17 as it rolls out its stimulus measures, including spending on infrastructure and enhanced child benefits. Last month the first payments under the new Canada Child Benefit went out to households, with some economists predicting it will add 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points to GDP this year due to higher consumer spending. All told, the government forecasted that its budget measures would add 0.5 percentage points to GDP.

Which raises the question: At what point do the dismal jobs numbers, weak exports and slumping GDP become a political problem for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau?

The Conservatives are certainly trying to pin the blame for the stumbling economy on Liberal policies. “Canadians have no reason to trust the Liberal Government when it comes to Canada’s economy,” Lisa Raitt, the party’s finance critic, said in a statement on Friday. “The Liberal Government claimed that if it borrowed tens of billions of dollars, it could grow the economy and create jobs. In reality, the Liberals have failed to deliver results for middle-class families and the Canadian taxpayer will be left to pay the bill.”

In reality, the Trudeau government is only nine months into its first mandate, and less than five months have passed since the Liberals brought down their 2016 budget. For now, at least, the polls suggest Canadians are willing to accept the government’s position that it inherited a slow economy made worse by shocks like the Fort McMurray fires.

Yet a key plank in the Liberals’ election campaign was that Trudeau would bring a more activist government to Ottawa capable of engineering stronger growth through deficit spending—all in contrast to his predecessors low-tax, laissez-faire approach. (Never mind that there’s really little that any government can do in the short term to influence the economy.)

Whatever the polls say now, there’s a limit to how long Canadians will support the Trudeau government if its big deficits and bold promises don’t at least appear to deliver good news soon.