The risk we all face but aren’t talking about

Getting sick is something we all face. But, what happens to you in such a situation depends very much on where you work and who you work for.

Shutterstock

Share

Child benefits, income splitting, pensions, flexible work arrangements and compassionate care leave—this federal election is putting social policy in the window. But if we are going to have a much-needed conversation about how Canadians are dealing with the various demands of work, care, and aging then we are missing one very big element: what happens to you if you get sick.

By this, I am not referring to the health care system, but rather: what happens to your job, your income and your family’s standard of living if you become ill?

This isn’t a trivial question. In a given year, approximately six per cent of Canadian workers are forced to change their work status due to a personal illness or disability, either taking an extended leave from work, changing the number of hours they work, or leaving the labour market entirely.

Getting sick is a risk we all face. But, what happens to you in such a situation depends very much on where you work and who you work for.

First, there is a huge discrepancy between provinces in terms of the minimum amount of time employers must offer in terms of sick leave (almost uniformly unpaid). This can range from no entitlement in provinces like Alberta, to as much as 26 weeks in Quebec. Many employers accommodate employees with paid or unpaid leaves greater than the minimum required under labour law, but the point is that we have no common baseline.

Second, how much income and employment support you would receive during the period of illness is unclear. Canada’s approach to sickness and disability insurance assumes that all workers should be privately insured, and that private insurance will be the first payer before any public support program. While this is a perfectly acceptable approach, many workers are not adequately insured.

As of 2013, about 44 per cent of workers were not enrolled in a private, long-term disability benefit plan. As with pensions, group benefits and other characteristics of a “good job,” coverage for disability insurance varies significantly between those working full- and part-time, for large and small employers, and in high- and low-wage industries.

Though not without its own problems, private disability insurance often provides a higher level of income replacement and a wider suite of support services than is typically available in public programs. Unbeknownst to many, the sickness benefit offered under Employment Insurance (EI) only provides 55 per cent wage replacement, lasting no more than 15 weeks. Moreover, EI offers no active employment supports to help you or your employer ease your transition back to work; if you work even intermittently, every dollar you earn will be clawed back.

Aggravating this situation are other serious problems, including a significant lack of coordination from one program to the next, and an outdated concept of disability around which parameters of eligibility are set.

Approximately one in three workers who go on EI sickness benefits exhaust their claim after 15 weeks. Assuming their illness isn’t severe or prolonged enough to qualify as a permanent disability (think of someone with a cancer diagnosis) the worker likely won’t be eligible for the Canada Pension Plan Disability benefit. If they don’t have private LTD, three options remain: seek a paid leave from their employer; draw down on personal savings; or apply for general welfare. To these workers, we are saying, in effect: you are sick but not disabled enough.

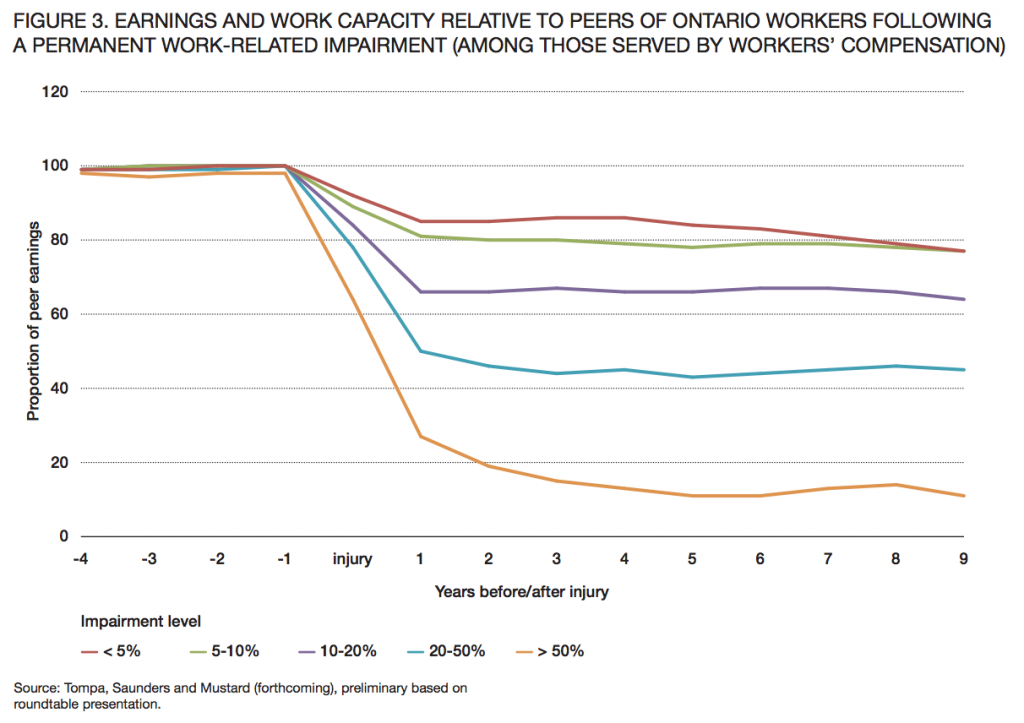

Failing to properly support workers and employers to navigate the difficult circumstances presented by an illness has long-term consequences. Emerging evidence from the related field of workplace injuries suggests that the drop in earnings and employment experienced by an affected worker is often disproportionate to the level of impairment.

The costs are broader still. In 2010, Canadian governments and insurance carriers spent nearly $30 billion in direct financial assistance to persons and families who got sick. Billions more are forgone in lost productivity, while, at a personal level, many families cope with the pressures of care and work.

In an aging population we can’t afford to ignore these issues. If good social policy is good economic policy then we need to hear from all of the political parties about how they propose to fix Canada’s system of sickness and disability supports.

Tyler Meredith is a research director at the Institute for Research on Public Policy, and co-author of the recently released paper, Leaving Some Behind: What Happens When Workers Get Sick.