Off-Target: How a U.S. retail giant misread the Canadian market

What the demise of Target’s Canadian stores says about the outlook for the country’s economy

LOS ANGELES, CA – SEPTEMBER 17: CNN reporter Soledad O’Brien poses with Bullseye, the Target dog, at the 2009 ALMA Awards held at Royce Hall on September 17, 2009 in Los Angeles, California. Chris Weeks/Getty Images

Share

On paper, at least, Target Corp.’s ill-fated 2011 decision to enter Canada by paying $1.8 billion for the leases of a few hundred Zellers stores seemed like a no-brainer. Canada, unlike the U.S. at the time, was a bastion of economic opportunity—or so it appeared. Our banks were healthy, house prices were rising and consumers were spending more on clothing and housewares than ever before. Best of all, Target’s own research showed that as many as 10 per cent of Canadians were already crossing the border to shop in its sprawling, red-and-white U.S. stores, and that 70 per cent were familiar with its “cheap chic” brand.

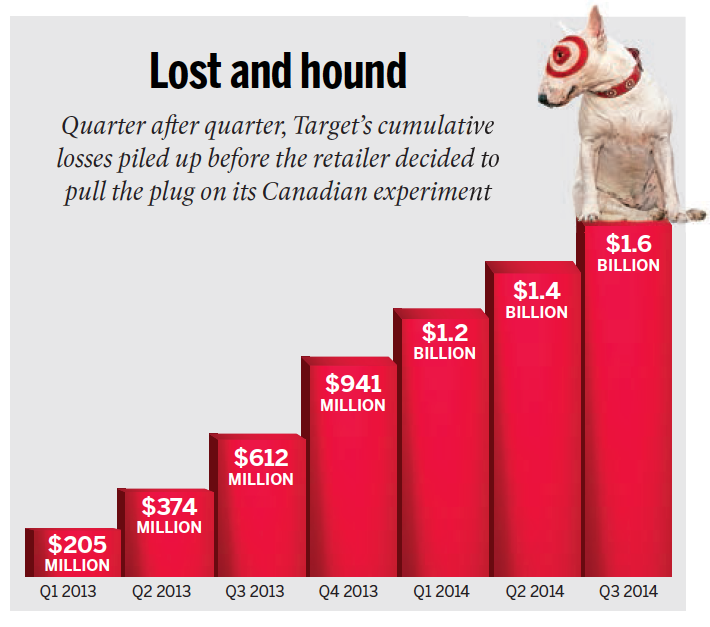

Less than two years later, the Minneapolis-based giant is pulling out of Canada after amassing $2.5 billion in pre-tax losses. The collateral damage: 133 stores closed across the country, 17,600 jobs lost and a huge, $5.4-billion write-down for the U.S. parent company. So much for Target’s much-ballyhooed bid to change the face of Canadian retail.

Target’s failure to take Canada has been chalked up to an overly ambitious launch, which included the rollout of 124 stores the first year, and problems with inventory control systems that left store shelves bare. Stores struggled to keep key items such as milk and eggs in stock, while photos on Twitter showed empty aisles, save for a few packages of men’s underwear. More harmful, though, was the perception—not always supported by fact—that Target was more expensive than rivals like Wal-Mart. Despite a concerted effort to get things back on track in 2014, Target CEO Brian Cornell said in recent blog post that executives were “unable to find a realistic scenario that got Target Canada to profitability until at least 2021.”

What’s surprising about Target’s Canadian misadventure isn’t that it ran into unforeseen problems. It’s that it didn’t think there was any point in trying to fix them. To be sure, the company was being pressured by investors to improve performance following an infamous data breach in 2013. But one could hardly imagine Target abandoning the state of California, with roughly the same population as Canada, just because it experienced a few teething problems.

Although it wasn’t cited as a reason in Target Canada’s bankruptcy filing, Canada’s rapidly deteriorating economic climate almost certainly hastened Target’s decision to snap a leash on its bull-terrier mascot and head home. Target’s announcement came the same day that Sony Canada closed all 14 of its stores, and federal Finance Minister Joe Oliver announced he was delaying the federal budget because of collapsing oil prices, which threaten to erase surpluses and plunge parts of the country in recession. “They’re looking at a lot of different metrics, and consumer spending would be one of them,” says Peter Chapman, a former Loblaw executive and retail consultant in Halifax. “What we’re seeing in the oil industry and the ripple effect on the economy is huge.”

Related:

Why Target missed its mark so badly

Hey Target, here’s how you expand into Canada, courtesy of Wal-Mart

A saturation of the Canadian retail market may have also factored into Target’s decision. Twenty years ago, Wal-Mart, a discount chain whose arrival was more likely to generate protests than the fawning newspaper coverage enjoyed by Target, managed to successfully colonize Canada with a similarly rapid expansion after it bought 122 Woolco stores. But much has changed since. A long line of U.S. retailers, from J-Crew to Lowe’s, have followed Wal-Mart northward in recent years, each laying a claim to a piece of Canadians’ wallets. Target, in other words, may have simply come too late to the party (to the extent there ever was one)—a realization that should have other U.S. retailers thinking twice about tapping Canada for easy growth.

The outlook for the Canadian economy in early 2015 is far worse today than it was six months ago—around the time Target Canada president and company veteran Mark Schindele was readying a turnaround plan for the struggling Canadian operation. Citing the plunge in oil prices, U.S. investment bank Morgan Stanley, for example, recently downgraded its GDP growth forecast to 1.8 per cent this year and 1.5 per cent in 2016—a full percentage point lower than its previous estimates. By contrast, most economists expect the U.S. economy to grow at three per cent over the same period, with falling energy prices acting as a stiff tailwind. In the Prairies, where the collapse in oil prices is wreaking the most havoc, there is even talk about Alberta being thrown into recession, a marked turnaround from previous years when the province led the country in employment growth. Suncor Energy has already laid off 1,000 workers and there’s likely more pain to come with oil now below US$50 a barrel.

What’s more, the oil-induced hangover could be exported elsewhere, with Ontario having become more reliant on manufacturing specialized equipment for the oil sands in recent years. It all adds up to a rather alarming picture, given that Canadian households now owe a record $1.63 for every dollar they earn. Economists have frequently warned that elevated debt levels make Canada vulnerable to economic shocks—such as wild swings in energy prices.

Even before oil prices collapsed, U.S. retailers were taking an increasingly cautious approach to Canada. A report earlier this year by U.S. commercial real estate firm CBRE found that Canada went from being the sixth-most desirable market for global retail expansion in 2012 to not even on the list in 2014. Nordstrom, for example, decided earlier this year to delay the launch of its discount chain, the Rack, in Canada until 2017.

The growing trepidation is only partly due to the weakening Canadian economy. Foreign retailers—and U.S. chains, in particular—have long assumed Canada is under-served by retailers. The country currently has about 15 sq. feet of leasable shopping-centre square footage for every person in the country, compared to about 25 sq. feet per person in the U.S., according to Colliers International. But, despite all the recent arrivals to the Canadian retail scene since the recession, the gap between the two countries has remained fairly constant over the years. We simply don’t seem to need new retail space. For every shiny new J-Crew that’s popped up in the local shopping mall, there’s been a Jacob store that’s gone out of business. In recent years, the number of retailers that have announced store closures or ceased operations entirely in Canada include: Sony (14 stores), Smart Set (107 stores), Jacob (92 stores), Mexx Canada (95 stores), Sears Canada (five stores), Big Lots and Liquidation World (78 stores) and, of course, Zellers, which had its 22 locations sold to Target.

Target’s slogan is, “Expect more, pay less.” But Target Canada initially appeared to deliver on neither. Although the company’s Ontario stores attracted plenty of curious customers after opening in early 2013, it wasn’t long before shoppers complained about Target’s prices and analysts started asking tough questions. “While shoppers appreciate the higher quality assortment, especially in discretionary categories”—more KitchenAid mixers and cute area rugs—“the complaints on pricing were alarming,” Deutsche Bank securities analyst Paul Trussell wrote two years ago.

The problem, it turned out, was that shoppers weren’t comparing prices against Target’s Canadian competitors, but against its own U.S. stores, which was bound to be a recipe for disappointment in a country where many products can cost up to 25 per cent more than in the U.S. J-Crew, the popular U.S. clothing retailer, ran into a similar snag when it opened its Canadian stores in 2011 and immediately faced a pricing backlash from shoppers accustomed to buying through its U.S. website. The effect was magnified for Target, however, because there had been so much hype prior to the chain’s launch. “When Target was coming in, they were only too happy to get the media machine behind them,” says David Ian Gray, the founder of DIG360 Consulting in Vancouver. “But when they fell short, it created an even bigger perceptual gap.”

Target responded by making sure it was meeting or beating Wal-Mart Canada on everyday products such as toilet paper and breakfast cereal. Even so, Chapman says Target didn’t try hard enough to shake its pricey perception among Canadians. “If you’re a retailer teetering on the edge, you’ve got to pile it high at the front of those stores,” he says. “They might have narrowed the price with Wal-Mart, but they sure didn’t tell anyone about it.” In part, that’s because Target has traditionally eschewed the traditional discount approach in order to give its stores a more organized, higher-end feel—hence, the whole “Tar-zhay” moniker. But that only works if people are already walking through the doors, Chapman says. Another frequent complaint was empty shelves. A report by Reuters suggested that barcodes on products didn’t always match up with what was in the computer system, creating backlogs and shortages as staff attempted to sort things out. A post on the website Gawker, purportedly written by a “management-level employee,” also blamed Target’s Minneapolis headquarters for trying to force its processes and procedures on the Canadian operation despite evidence they weren’t working. Others, however, heard rumours Target Canada was reluctant to ask Minneapolis for help when it was in over its head. Either way, it was hardly the well-oiled machine many had expected.

Of course, supply chain snafus aren’t unheard of in the industry. Loblaws has suffered from them, and so has the Brick. Both recovered. And Target appeared to be on its way to doing the same after Schindele was brought in to replace Tony Fisher as Target Canada’s president last spring. But Target had left itself little margin for error after spending $1.8 billion for the Zellers leases and another $2.3 billion to renovate the stores themselves, about double the initial estimate. “The hole was too big,” says Scott Mushkin, an analyst at Wolfe Research in New York. He says Target Canada was only selling about US$140 worth of merchandise per square foot when it needed to be moving closer to US$250 a square foot to break even. By comparison, most of Target’s U.S. stores manage US$300 a square foot, which is the number Target Canada would have had to hit to realize its stated goal of reaching US$6 billion in sales by 2017.

Interestingly, however, Mushkin doesn’t believe Target’s supply-chain problems or pricing ultimately led to its undoing. Instead, he argues there simply wasn’t sufficient consumer demand for another big discount retailer in Canada, and that Target failed to provide consumers with a compelling reason to switch their shopping allegiances. The initial missteps and the deteriorating economic picture only served to hammer home the point sooner than might have otherwise been the case.

After visiting several stores in Toronto late last year, Mushkin wrote in a note to clients that, “Overall, we found the shopping experience in-store quite pleasurable and didn’t see any areas of major concern.” Similarly, he suggested that pricing comparisons with Wal-Mart Canada suggested Target shoppers were getting a “good deal,” once loyalty program discounts were included. Mushkin concluded that the only explanation for Target Canada’s poor performance was that Canadian consumers were already well-served by existing players, many of whom had upped their game in preparation for Target’s arrival, and that the operation should be mothballed. “In the end, Target is a great retailer,” Mushkin says. “But was there a real need in Canada? The answer is no.”