Population growth isn’t driving Toronto house prices. So what is?

While Toronto house prices have soared, the latest census figures show population growth in the city has begun to slow

A construction crane stand in front of the CN tower in downtown Toronto on Saturday, February 4, 2012. The condo explosion is changing the shape and culture of Canada’s cities. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Pawel Dwulit

Share

Last summer, in the frankest terms possible, Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz warned home buyers, homeowners, mortgage lenders and the real estate industry that nothing justified Toronto’s skyrocketing house prices. Nothing. Zip. Zilch. Nada.

Toronto didn’t get the message.

In its recent outlook for 2017, the Toronto Real Estate Board said it expects the average house price in the greater Toronto area to surge by another $100,000 this year to $825,000. That would be on top of a $120,000—or roughly 20 per cent—increase in 2016. In making its forecast, the board repeatedly credited one factor for driving higher prices in Toronto: population growth.

Well, earlier this week Canadians got their first look at the results of the 2016 census, when Statistics Canada released population and dwelling counts for the country. And while the overall trend saw stronger population growth in urban centres, Toronto’s showing was rather middling.

The population growth of Toronto’s census metropolitan area slowed considerably between the last two census periods. The city grew by 6.2 per cent over the 2011 to 2016 period, compared to 9.2 per cent between 2006 and 2011. In fact, it was the slowest census-to-census growth rate Toronto has experienced in at least 40 years.

There’s a caveat to mention here. Over time the boundaries of Toronto’s census metropolitan area (CMA) have expanded, and so some of the population increases in the past were partly a result of this expansion. However StatsCan also said in an email that since the 1990s boundary changes have been minimal.

Yet despite the city’s modest population growth—Toronto only managed to top the national average by 1.2 percentage points—house prices have surged. Here’s that same chart, but this time including real (inflation-adjusted) house price growth between census years. Granted, the Toronto CMA covers a larger area than is captured by the Toronto Real Estate Board’s statistics, but as CMHC has noted, staggering price gains have spilled out of Toronto into its environs.

Never has there been a five-year stretch when Toronto house prices soared as fast as they did between 2011 and 2016.

(Post update: Below is a different version of the same chart showing totals, rather than percentage changes, since some have pointed out on Twitter that a smaller percentage change on a larger population base could still be a larger increase than in the past. However as the chart shows, the Toronto CMA population grew by the smallest number of people of any census period in decades. The disconnect between house price gains and Toronto’s slower population growth appears even starker.)

So what’s driving the market?

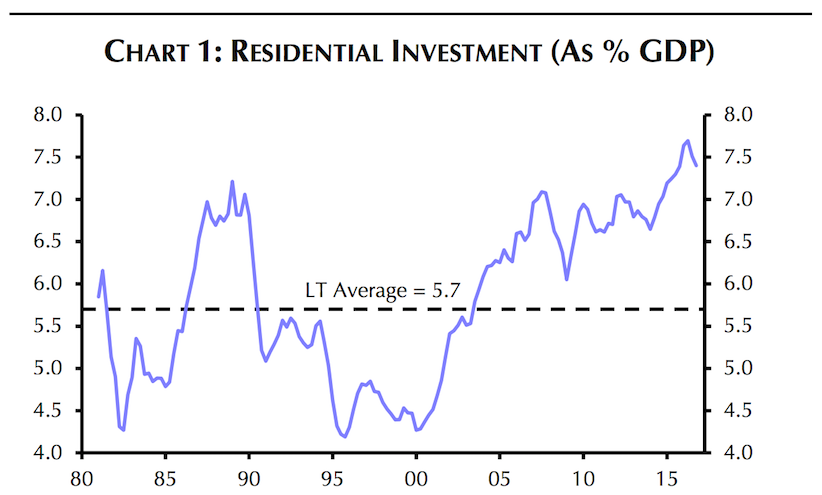

Wild-eyed speculation, according to David Madani, an economist at Capital Economics and a noted housing bear. Madani released a report Friday saying that imbalances in the housing market are worsening, and could become a drag on the nation’s long-term growth. Investment in housing, which has supported the Canadian economy through recent tough patches, has reached and remains near record highs.

However the peak may have come. Madani pointed to the steep decline in housing sales in Vancouver, which have fallen 44 per cent since February 2016, noting that no macroeconomic shocks explain the drop. Mortgage rates remain incredibly low, despite mortgage rules being tightened by Ottawa. Meanwhile, employment growth has been relatively strong in that city. He also argued that the foreign buyer tax, introduced last August, doesn’t fully explain the collapse in sales either. “We simply think the housing bubble has burst,” he wrote. “Housing bubbles are, of course, inherently unstable because they are largely driven by unpredictable investor mania.”

And that brings us back to Toronto’s housing market, which Madani believes is being driven by “increasingly riskier” lending practices; the average home loan has ballooned relative to household incomes, he said, while mortgage lending is shifting away from traditional banks to unregulated firms.

All of this should be a concern for Toronto, as well as the Canadian economy at large, he concludes. “The abrupt slowdown in Vancouver’s housing market should serve as a warning shot. As things stand now, the economy’s performance this year could hinge on Toronto’s overheated housing market.”