The loonie, oil’s crash, and why this isn’t anything like 2008

As you watch the oil price, keep the Canadian dollar in mind before you hit the panic button

Share

Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz, a master of the econo-metaphor, has described the relationship between the Canadian dollar and oil in many colourful ways—as oil drops, the impact on the terms of trade might not immediately impact the dollar, but, “like walking a dog on one of those leashes that stretch out and snap back,” the value of oil and the value of the dollar will be linked. Over the past couple of weeks, the dollar has been pulling a lot of leash off the reel, depreciating rapidly against the U.S. dollar as oil dropped. The impact has been stark, especially in the longer-term outlook for oil in Canadian dollar terms. The question producers must be asking is whether a sub-90-cent dollar is a long-term reality, or whether the leash will snap back and leave Canadian producers and governments feeling a much greater hit from the drop in world oil prices. Still, no matter what happens with the Canadian dollar as the oil shock propagates through the global economy, this is a long way from 2008.

Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz, a master of the econo-metaphor, has described the relationship between the Canadian dollar and oil in many colourful ways—as oil drops, the impact on the terms of trade might not immediately impact the dollar, but, “like walking a dog on one of those leashes that stretch out and snap back,” the value of oil and the value of the dollar will be linked. Over the past couple of weeks, the dollar has been pulling a lot of leash off the reel, depreciating rapidly against the U.S. dollar as oil dropped. The impact has been stark, especially in the longer-term outlook for oil in Canadian dollar terms. The question producers must be asking is whether a sub-90-cent dollar is a long-term reality, or whether the leash will snap back and leave Canadian producers and governments feeling a much greater hit from the drop in world oil prices. Still, no matter what happens with the Canadian dollar as the oil shock propagates through the global economy, this is a long way from 2008.

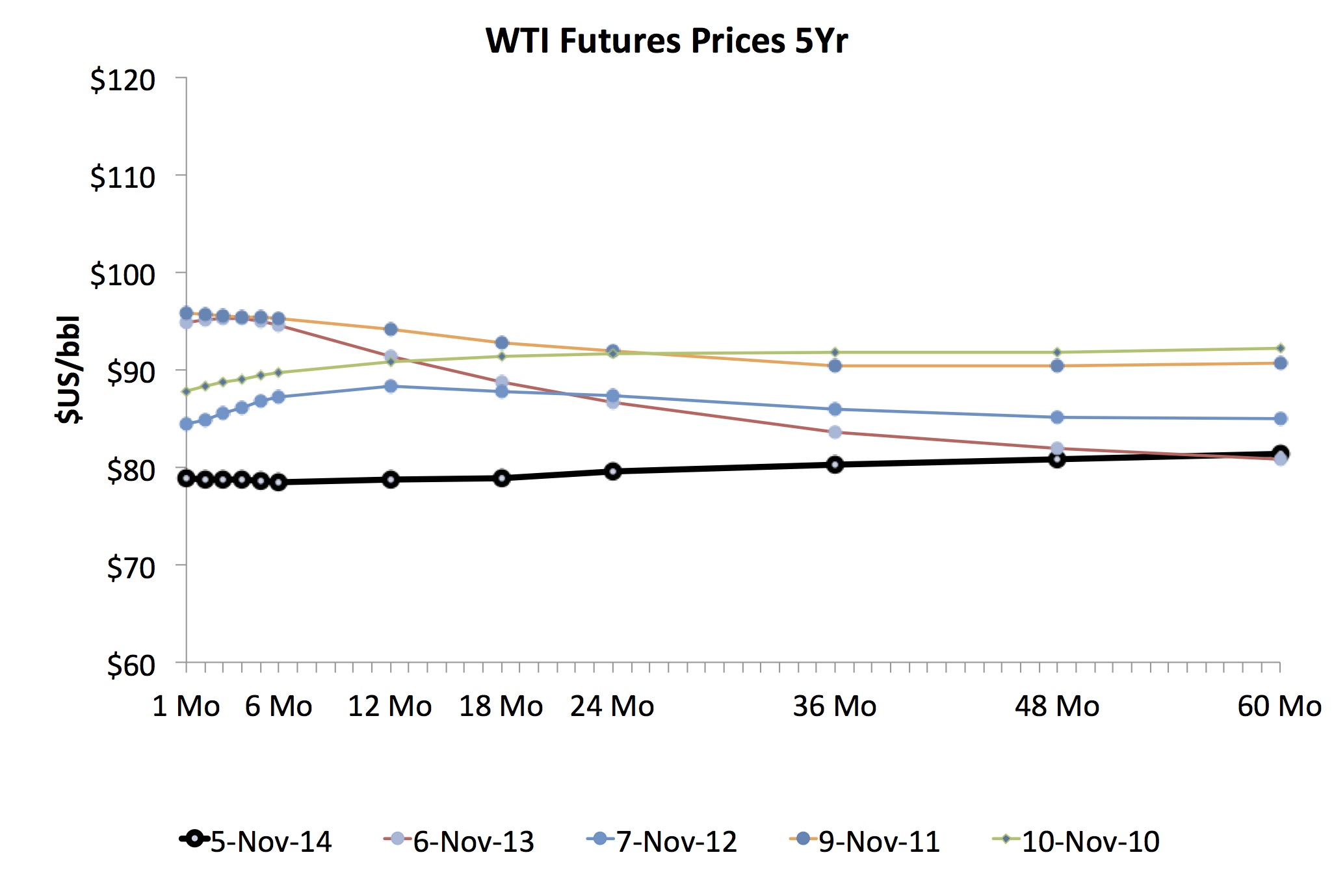

Let’s start with a look at oil in U.S. dollar terms—over the past month, we’ve seen oil prices for the West Texas Intermediate crude benchmark at their lowest point since mid-2010, with prices holding well-below $80 per barrel. As you can see in the graph below, this is not simply viewed as a short-term fluctuation—the futures market has oil barely above $80 60 months from now — a forward view of oil about as bearish as it has been over the past five years.

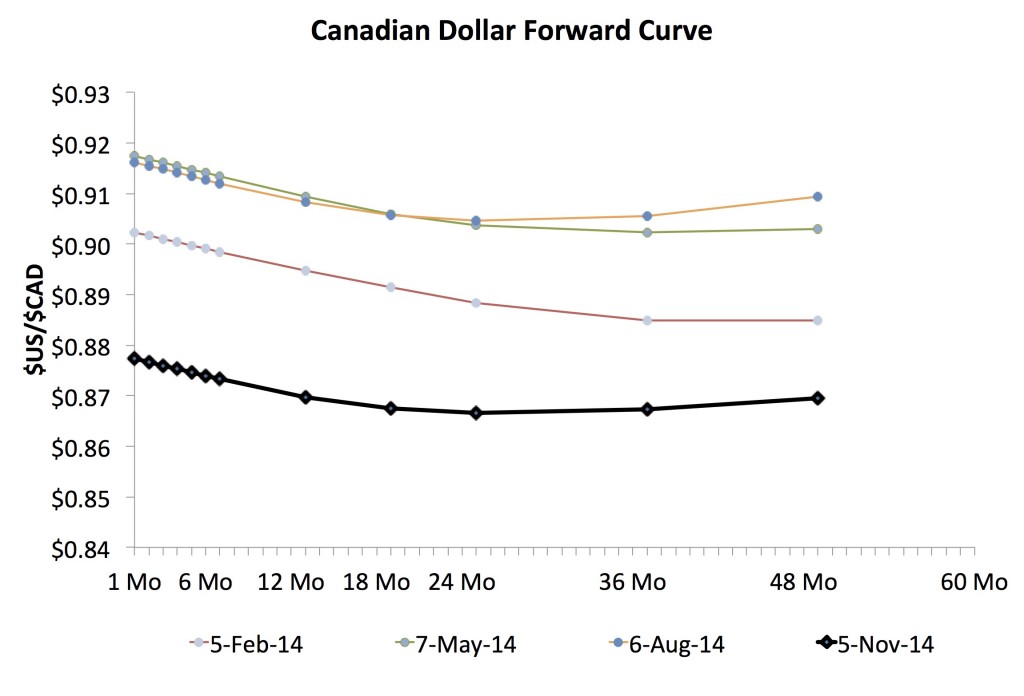

Over the same period of time as oil’s recent decline, the Canadian sollar has seen an equally rapid fall, as shown below. If we look just over the past year, the slide has been dramatic, with much of the drop happening since oil’s global slide started to accelerate in the late summer. In the first six months of the year, as oil was appreciating, the Canadian dollar had begun to climb slowly again.

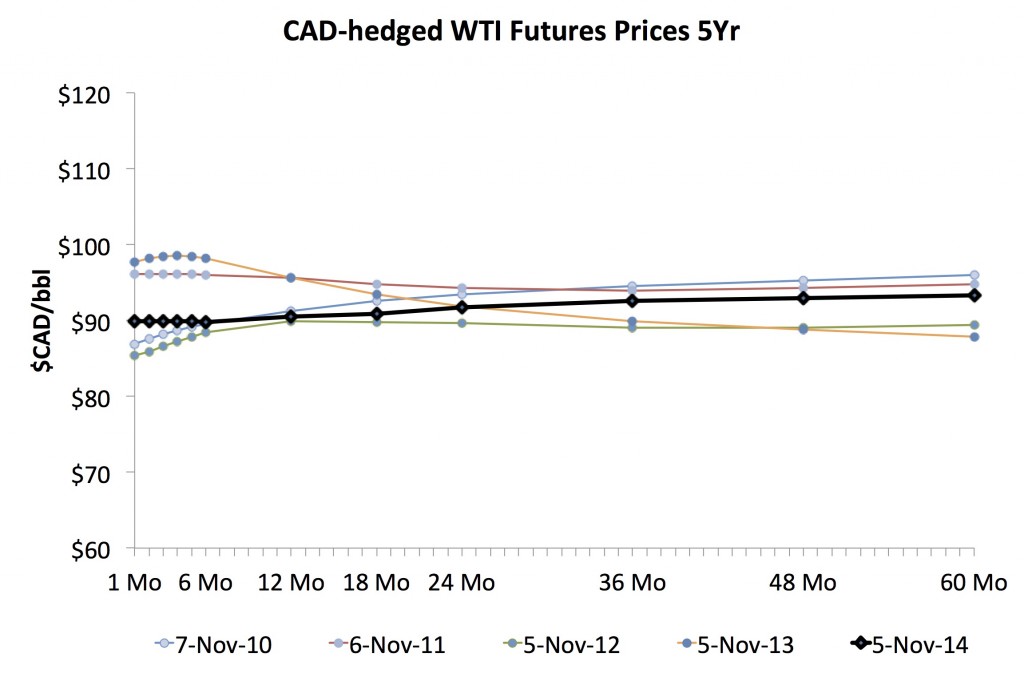

If you combine these two curves and ask what the $CAD-hedged future price of oil (the Canadian dollar price at which you could lock in future oil purchases or sales) has done over the past six months, you get a very different story than that which you’d see if you looked only at the WTI forward price alone.

With the impact of the Canadian dollar taken into account, the long view on oil in Canadian dollar terms is not anywhere near as bearish as you might think. In fact, looking three to five years out, which would be the relevant time horizon for the start-up of a new oil sands projects, the market is now reflecting expected future cash flows higher than we’ve seen in at the same period each of the last three years — the question, as I mentioned above, is whether the Canadian dollar has run too far, and that leash will snap back. However, it would have to snap back a fair bit, especially in the long term, to make this year’s oil prices look worse than 2012’s or even last year’s long view.

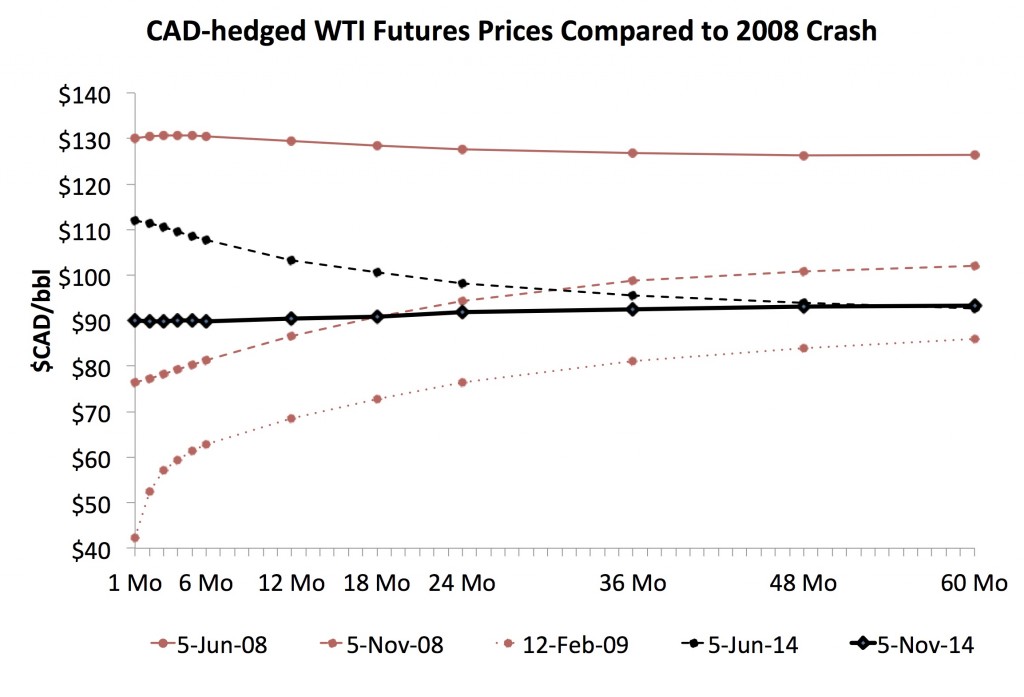

To put this recent drop in oil prices into perspective, the Canadian dollar doesn’t always buffer producers against a fall to the degree that it has this time around. In the figure below, you can see five forward curves, a comparison between this year’s June and November curves, hedged in Canadian dollar terms, compared to the same time periods in 2008 over which time the financial crisis was just beginning to take hold. For reference, I’ve also included the Feb. 12, 2009 curve, the week in which WTI hit its lowest value during the crisis.

In June, 2008, a Canadian producer could lock in future production at or around $130 Canadian dollars per barrel. Within five months, this had dropped to a little over $100 in the long term. Within another three months, crude bottomed out, with spot prices more than 50 per cent lower than those we see today, but with significant optimism looking ahead. Over the past five months, we’ve seen a drop a little less than half as large in the front end of the oil price curve as what was seen over the same period in 2008, and we’ve seen virtually no drop at all in the long-run view in Canadian dollar terms. That should give producers, and Alberta’s new premier, some relief.

So, what’s the bottom line? Over the past four months, the Canadian dollar has done what you’d expect it to do—it has acted as a shock absorber, buffering the Canadian economy from a significant commodity shock. Of course, this shock absorption isn’t free—it comes at the expense of our global purchasing power and, thus, Canadians’ real wages and real wealth, but it’s important to recognize nonetheless. The as-yet-unanswered question is whether, channeling governor Poloz, the shock absorber has bottomed out and we should expect a hard rebound, or whether there’s still travel left in the system. Over the coming weeks, as you watch the oil price, make sure to take a quick peek at the Canadian dollar as well before you hit the panic button.