The national housing strategy promises big spending, but is it money well spent?

Opinion: With homelessness funding not tied to outcomes, tens of billions of new spending from Ottawa might not help nearly as much as it could

(Jae C. Hong/AP)

Share

Kevin Page is President and CEO of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa and Co-Chair of the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness. Randall Bartlett is the IFSD’s Chief Economist and Alannah McBride is a 4th-year economics student at the University of Ottawa.

National Housing Day is fast approaching and the National Housing Strategy is just around the corner. With this in mind, it’s a good time to do a stocktaking of how governments are doing with the billions of dollars already being spent on homelessness initiatives. The exercise was motivated by one fundamental question: Does the current funding structure for homelessness programs produce the desired results? Our full blogpost can be found here.

Hey big spender

At the federal level, the Government of Canada is currently planning to spend about $4 billion over the next 11 years on homelessness initiatives. Of course, this is all about to change with the announcement of the National Housing Strategy. While details are scant, what we’ve heard so far is that the federal government is planning to commit about $40 billion over the next decade to housing and homelessness.

READ: Liberals ready to make housing a right as part of national strategy

But the federal government isn’t the only level of government that spends on homelessness initiatives. The provinces and territories play a part as well. The Government of Ontario, for instance, also spends hundreds of millions of dollars annually on homelessness initiatives.

And while the numbers may be big when announced at the federal or provincial-territorial level, the rubber really meets the road when it trickles down to the municipalities. Take Ottawa as an example. From higher levels of government, it received over $73 million in the 2016-17 fiscal year, which it then topped up with an additional $9.3 million of its own funding.

Money for nothing and the cheques are free

Looking into the funding for homelessness initiatives and the associated outcome reporting, the IFSD found that funding from the Governments of Canada and Ontario do not generally appear to be tied to outcomes, best practices are not necessarily shared across jurisdictions, and data do not appear to be collected in a way that allows them to be used across programs and jurisdictions.

But just because funding isn’t tied to outcomes doesn’t mean that the outcomes themselves are poor. In order to evaluate that, you need to look to those programs where outcome reporting is required. Fortunately, there is a program to address chronic homelessness offered in Ottawa that does allow for comparisons. That is the Housing First program provided with federal funding as part of the Homelessness Partnering Strategy (HPS). (One of our coauthors, Randall Bartlett, wrote about Housing First in Maclean’s in August 2017.)

READ: There’s a better way to fight homelessness than emergency shelters

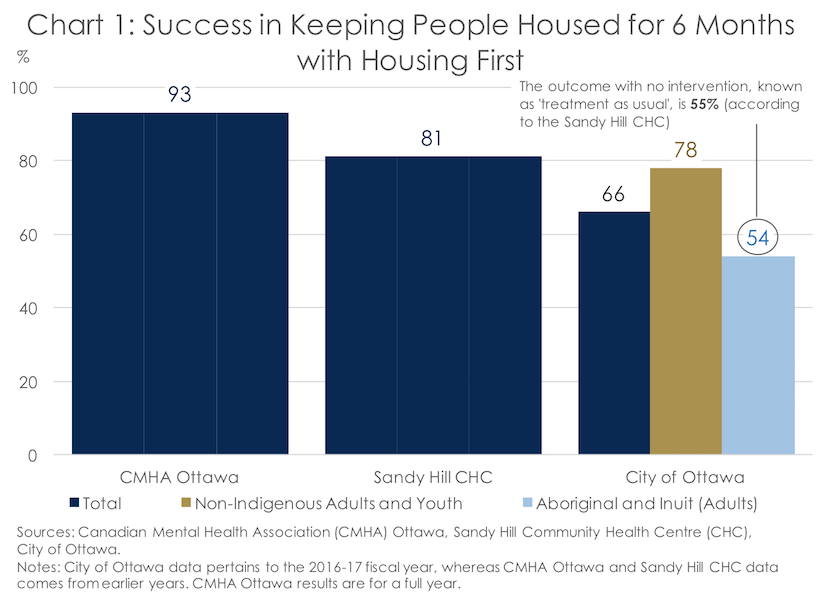

Again, similar to the broad conclusion about the link between homelessness program funding and outcomes, the City of Ottawa is receiving federal funds but not delivering results in line with its peers. In comparing the outcomes of various service providers, the differences are striking. The Canadian Mental Health Association Ottawa’s (CMHA Ottawa’s) Housing First program achieves a 93 per cent success rate in keeping single people stably housed for six months or more, while the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre’s (Sandy Hill CHC’s) program isn’t far behind at 81 per cent. However, the City of Ottawa Housing First program comes in at 66 per cent—well below the 80 per cent threshold seen as normal for Housing First (See chart 1 below). Further, among Aboriginal and Inuit adults, the success rate in keeping people housed for six months or more is a dismal 54 per cent—roughly equivalent to the outcome over the same period when there was no intervention. This means Aboriginal and Inuit adults who are chronically homeless end up no more likely to be housed after six months in the City of Ottawa’s Housing First program than out of it. Meanwhile, by all appearances, the City of Ottawa has continued to qualify for HPS-funding for Housing First from the federal government despite this poor outcome.

What this means

This analysis was intended to highlight the fact that much of the funding for homelessness initiatives—be it at the federal, provincial, and municipals levels—is not tied to outcomes. This is a problem, as well-intended funding to support our communities’ most vulnerable may be being spent in a manner which does not meaningfully help those people. And, with the National Housing Strategy just around the corner, this could mean tens of billions of dollars spent on programming that doesn’t help homeless people or people at risk of homelessness nearly as much as it could.

As legendary basketball coach John Wooden once said, “Never mistake activity for achievement.” Major announcements don’t mean major change. In order for the National Housing Strategy to meaningfully affect change, all levels of government must ensure that funding is tied to the desired outcomes. And as a reflection of the diversity of Canada, this funding must also take into consideration demographic, geographic, and other confounding factors.

It’s a long road ahead to eliminate chronic homelessness in Canada. It’s up to all levels of government to make sure that road is paved with more than good intentions.

MORE ABOUT HOMELESSNESS:

- Liberals ready to make housing a right as part of national strategy

- There’s a better way to fight homelessness than emergency shelters

- ‘Tell them Chrissy sent you’ resonates in shelters across Canada

- Liberals set homeless reduction targets ahead of provincial talks

- Victoria’s longstanding homeless camp has been demolished

- UN: Canada’s national housing strategy needs human rights pillar

- Why ‘kindness meters’ are a horrible way to deal with panhandlers

- Saskatchewan gives two homeless men bus tickets to B.C.