The wishful thinking at the heart of the Alberta budget

The Alberta budget promises a return to balanced books by 2019/20 but relies on a big rebound in the price of oil to get there

Monster Truck in Alberta’s oil sands. Shutterstock.

Share

On Tuesday, Alberta’s first NDP government presented its first provincial budget. Government budgets are massive documents—this one clocks in at 128 pages—so there are far too many details to cover in one post. (And far too many for me to even understand.) But, here’s my take on the headline items that will likely be much discussed in the coming days and weeks.

In short, the deficit is big. This is neither surprising nor is it the result of the new government (as some might suggest). What’s more surprising, and a choice made by the government, is the lack of a concrete plan to eliminate the deficit. The government has a goal of balancing the books by 2019/20—and such a timeframe is reasonable—but the Alberta budget details only go out to 2017/18, so it’s tough to know what to make of their commitment. Changes in revenue are negligible, and rely on possibly optimistic oil price assumptions. Spending growth, while somewhat restrained, is still high in order to finance increased infrastructure investments. Based on Tuesday’s budget, the deficit over the next three years won’t shrink by much. Let’s get into some of the details.

How big is the deficit?

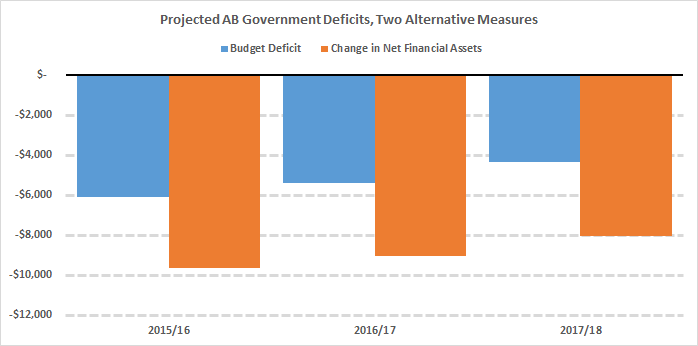

The Wildrose Shadow Minister of Finance, David Fildebrandt, said that the budget’s “real” deficit is $9.7 billion. But the budget (right on page 4) says the deficit is $6.1 billion. Who’s right? Both are. Let me explain.

If the government builds a hospital, a road, or some other piece of capital, it won’t record the cost right away, but will spread it out over the life of the project. That is, it will record the expense over many years, rather than the year in which the road was built. This is not at all unreasonable—and the way things probably ought to be done. But there are other measures. We could alternatively record as an expense the entire project right away. After all, the government needs money to pay for the hospital or the road. Why spread out the expense with book keeping entries when we need the money now? If we’re interested in the government’s revenue requirements, then we need another measure. In the budget, changes in “net financial assets” (basically just the government’s net worth) provides this alternative measure. They are both valid, and each is useful, though they can often be very different numbers. I plot them below. Mr. Fildebrandt is referring to the orange bars. The budget deficit is referring to the blue ones. They are both correct.

These are big numbers, to be sure, but no reason to panic. Alberta is in a very strong financial position and we should not have knee-jerk reactions to these deficit numbers. The important question is: What’s the plan to get out of deficit? Sadly, there isn’t much of one.

Oil prices and royalty revenues

Consider first the reason why we’re in this mess: low oil prices (and, of course, reliance on resource revenue as a source of government funding). If oil prices rise enough, the government is home free. Each dollar change in the benchmark oil price translates into a $170 million change in the budget’s balance. That is, if oil prices rise $10 (and this is sustained over a year) then Alberta’s deficit will shrink by $1.7 billion.

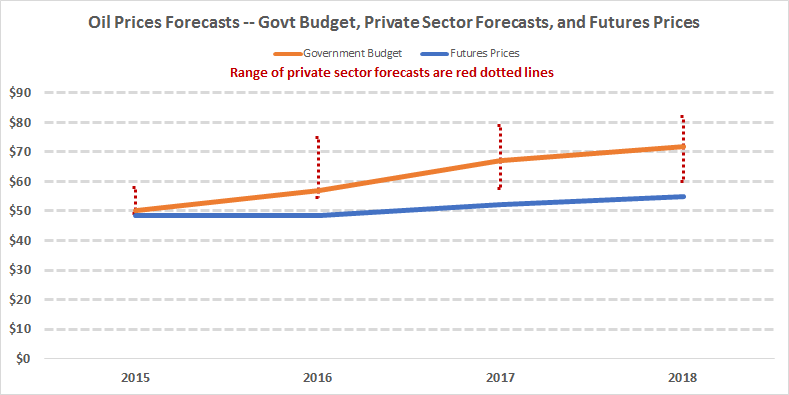

Getting price forecasts right is critically important, but an impossible task. So what can we do? The government turns to external private-sector forecasts and picks a value in the mid-range of those estimates. In Budget 2015, they choose a $50 per barrel price this year, rising to $72 by 2018. Below I plot this forecast against the range of private forecasts. The government is right in the middle of the pack.

Another way to forecast prices is to just look at market prices. Want a barrel of oil delivered in 2017 for a pre-determined price? Well, there’s a market for that. If we look at these prices—called futures prices—we see far lower oil price projections into the future than either the budget or the private sector forecasters suppose. “Lower for longer” is the saying, and some forecasters are already updating their numbers. By 2018, the government is budgeting based on an oil price $17 per barrel higher than current futures prices—equivalent to a $2.9 billion swing in the budget.

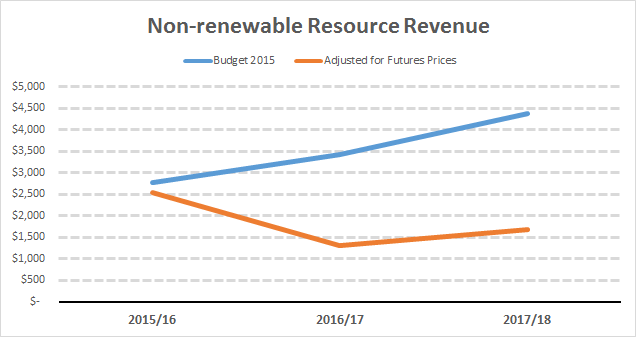

Just to illustrate the effect of such a difference in price, here’s the budgeted resource revenue versus what it would be if futures prices came true. (Not that they’re sure to come true, this just illustrates the importance of price changes.)

As futures prices reflect market prices of people placing actual trades with actual money, perhaps we should put more weight on futures prices than we do other forecasts. Of course, that doesn’t mean they are accurate predictors either. Two years ago, they certainly weren’t projecting our current low prices. So, no matter what the government does, they will be wrong. (For more on this, see this by Andrew Leach.)

Historically, these errors can be a huge fraction of government revenue. Below, I plot the deviation of budgeted revenue from actual resource revenues as a share of total government revenues. Sometimes, the actual revenues come in higher than forecast. In the 2005/06 budget, for example, the government budgeted $7.7 billion in resource revenue while the actual revenue was almost double that, at $14.7 billion. More recently, we’re seeing the flip-side of uncertainty, with far less resource revenues than we were counting on. These fluctuations are an important driver of overall surplus and deficit positions of the government—as is clear in the graph.

Does the budget help get us off volatile resource revenues? No. Albertans hopeful for a plan to move away from resources as a source of government funding will have to wait.

Government revenue and spending changes

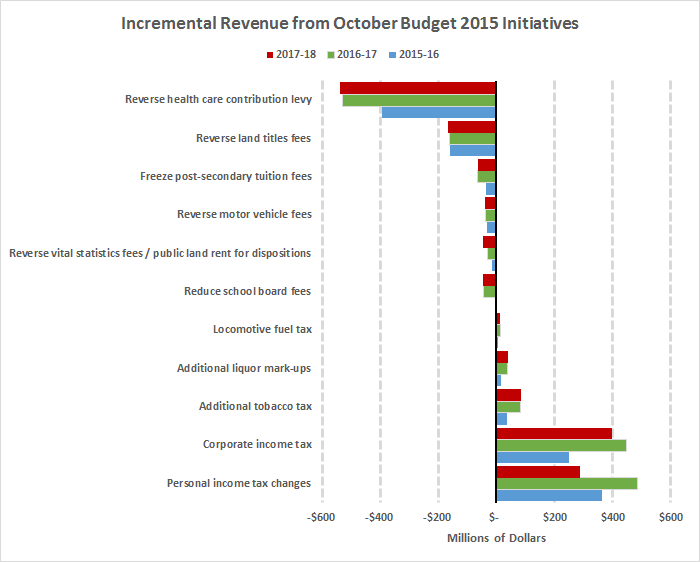

There are precious few options to close the gap left behind by low resource revenues. Increase other revenues (taxes), lower spending, or both. The budget does have tax changes (most of which were previously announced). The government increased corporate income taxes, raised personal income taxes on higher income individuals, and kept certain fee increases from the Prentice government (alcohol and gas taxes, for example). These raised revenue. But, the government also (sensibly) cancelled the planned Healthcare Levy, among other changes. Overall, the revenue increases are almost perfectly offset by the revenue decreases. Here’s the breakdown.

So, with little change on the tax revenue side of the ledger, what about spending restraint?

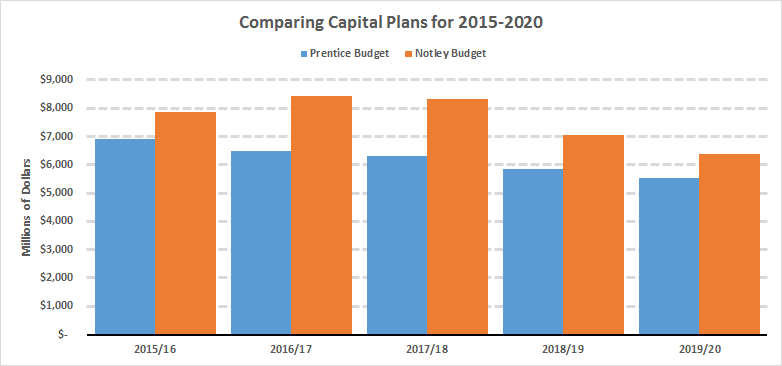

There are sizable increases in infrastructure spending. Relative to the Prentice budget earlier this year, there is an additional $6.9 billion in capital spending over the next five years.

What does this buy? There are lots of big ticket items planned over the coming years. The Edmonton and Calgary ring roads aren’t cheap (they’re allocated nearly $3 billion over the next five years). Then there is building 200 new schools ($3.8B), flood recovery and mitigation projects (almost $1B), or various municipal infrastructure projects ($8.6B).

The projects being funded may be entirely sensible. I have no idea. If a new bridge is needed, build it. If more schools are needed (which is absolutely true in Alberta), build them. This is a case-by-case decision that should be based on some reasonable cost/benefit estimates. But, if the aim of the new spending is to “create jobs” and “boost the economy,” then we have a problem. But, that’s a topic for another day.

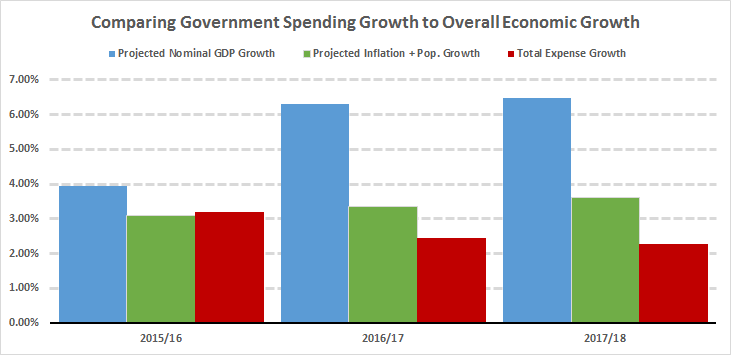

What about spending growth overall? The Alberta budget does have some fairly modest spending restraint. Over the next few years, spending is projected to grow at a slower rate than the combined rate of population growth and inflation—and much slower than the overall economy.

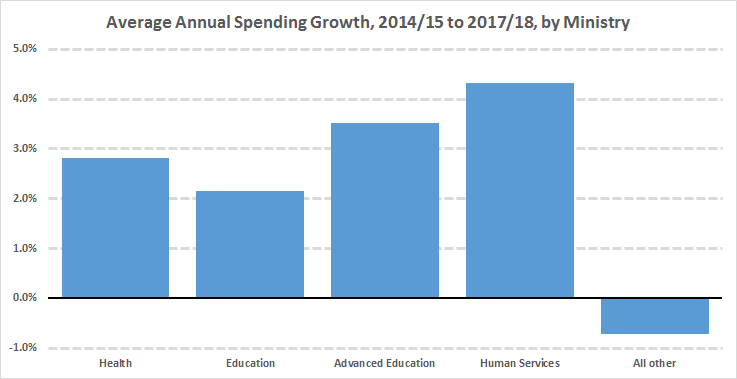

This is sensible though far less aggressive spending restraint than our current situation probably warrants. Since revenues tend to grow at the rate of nominal GDP, if we continue to hold spending at or below the rate of population plus inflation, then our deficit will gradually shrink—although far too slowly to have any hope of meeting the government goal of balancing the budget by 2019/20. With health spending, for example, accounting for 40 per cent of the budget, and with Alberta health expenditures per person among the highest in the country, surely there is room for improvement. The budget allows average annual health spending increases of 2.8 per cent per year to 2018.

Here’s the growth in the top four ministries (which together account for three-quarters of all expenses). Not a lot of spending restraint there.

All this being said, the government does reiterate a goal to balance the budget by 2019/20. But all of the important details in the budget end at the 2017/18 fiscal year. So it’s really hard to evaluate how realistic their balanced budget claim is. They basically presume revenue growth will jump to 7.3 per cent for 2018/19 and to 7.6 per cent in 2019/20 (without giving details), with spending growth of around 2 per cent (again, with no details).

I think they’re in for some difficult decisions ahead. We won’t have to wait long, though. The next Alberta budget is only five months away. Stay tuned.

Trevor Tombe is an assistant professor in the department of economics at the University of Calgary. Follow him on Twitter: @trevortombe