‘Tis the season: Indebted Canadians pull out the plastic

Canadians are among the world’s biggest users of credit cards. We make even Americans look prudent.

(Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press)

Share

As the holiday shopping season ticks down to its final minutes, many Canadians will make a flurry of last-minute pre-Christmas purchases before launching themselves into Boxing Day’s maw. And odds are, nearly all of those transactions will rung be up on credit cards.

The country’s love affair with borrowing—households in Canada owed a record $1.64 for every dollar of disposable income they earned in the third quarter, according to Statistics Canada data released this month—is matched only by our fondness for paying with plastic, despite interest rates on carried balances as high as 25 per cent.

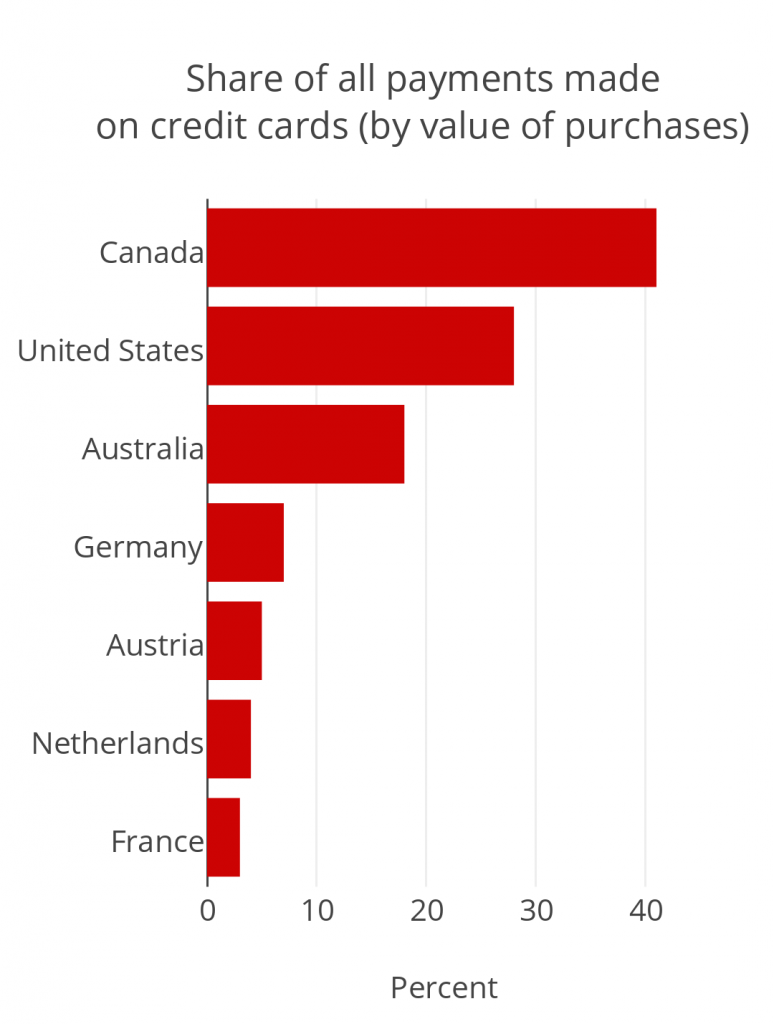

One Bank of Canada study last year found Canadians are among the world’s biggest users of credit cards, which account for more than 40 per cent of the value of their purchases. That’s even higher than in the United States, where President George W. Bush once famously urged Americans to demonstrate their resolve after the Sept. 11 terrorists attacks by going shopping.

Another study by Canada’s central bank earlier this year noted an 11 per cent increase in the volume of credit card transactions over the past five years, thanks to a “tripling of contactless credit card transactions.” In other words, the easier banks and credit card firms make it to swipe, insert or, now, wave their cards at the cash register, the more willing Canadians are to borrow and spend.

Not even Canada’s oil-shocked economy has caused Canadians to rethink the wisdom of buy-now, pay-later. If anything, the downturn has had precisely the opposite effect. An analysis earlier this month by credit agency TransUnion found average credit card balances heading into the holiday shopping season were at a two-year high at of $3,745. Jason Wang, the director of research and analysis for TransUnion Canada, cited a dearth of disposable income available to consumers in the oil patch (which may have resulted in more purchases being charged to cards) and the Bank of Canada’s two interest rate cuts this year (which makes carrying debt more affordable). However, Wang cautioned that, “In any economic environment, our advice to consumers is always to remember to spend within their means.”

The good news is most Canadians continue to make their monthly payments. In fact, the Bank of Canada’s recent financial system review found 55 per cent of Canadians view their credit cards as a convenient alternative to cash, paying off their balances in full each month. That’s up from 48 per cent of Canadians in the early 2000s. So while credit card spending has risen by about a third over the past 15 years, average outstanding balances have actually declined over the same period. One notable exception to the rule are wealthy households who rent their homes. This group is far more likely to carry balances on their credit cards—presumably because it’s more difficult for such households to access cheaper methods of borrowing like home-equity lines of credit.

Yet, despite increased evidence of responsible credit card use, the sheer number of credit cards in Canadian wallets and pocketbooks—about 72 million of them, complete with all manner of reward points and cash-back promises—serve as yet another example of this country’s love affair with debt, and our easy access to it. When coupled with more than $1 trillion in mortgage debt on the books, it’s no wonder Ottawa is worried about Canada’s ability to withstand another financial crisis. From the bank’s recent financial system review: the number of “highly indebted” Canadian households, meaning those with outstanding debts worth more than 350 per cent of gross income, has doubled to eight per cent since the 2008 financial crisis. Faced with a sudden drop in employment, many of these families could suddenly find themselves struggling to pay their mortgage, leading to a widespread downtown in the Canadian housing market. “The probability of this risk materializing is low, but the impact on the economy and the financial system would be severe if it were to materialize,” the central bank warned.

Already there’s evidence some Canadians are in over their heads. A recent survey by Manulife Bank suggested four of every ten Canadian homeowners were “caught short” at least once last year, meaning they had insufficient money in the bank to make their mortgage payment. And guess where a third of them turned? To the handful of high-interest credit cards burning a hole in their pockets.