What weak inflation means for Canadian consumers

Econ-o-metric: Inflation isn’t an issue for most of us, so the Bank of Canada won’t rush to raise interest rates

Loblaw: The company has reduced the number of plastic bags by six billion since 2008. (Loblaw Companies Limited)

Share

The cost of living in Canada grew the least in six months in May, Statistics Canada reported on June 23. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 1.3 per cent from a year earlier, compared with a gain of 1.6 per cent in April. The three “core” measures of inflation used by the Bank of Canada to predict where prices are headed also were weak in May, averaging 1.3 per cent.

The trend: Inflation remains a theoretical concern in Canada. Despite ultra-low interest rates, the monthly year-over-year change in the CPI has grazed the central bank’s two per cent target only three times since the start of the 2016. When the cost of food and energy is removed from the equation, inflation is even weaker. StatsCan’s gauge of core inflation hovered around two per cent between the summer of 2014 and the summer of 2016. That number has been falling steadily since August, and now sits around one per cent.

Glass half full: The Bank of Canada served notice last week that it is getting ready to raise interest rates, yet the inflation data suggest policy makers needn’t feel pressed. Canada’s central bank essentially has one job: to keep the CPI increasing at an annual rate of around two per cent. Inflation currently is trending well below that target. That’s a bit odd, given Canada’s economy has been growing strongly since the latter part of 2016. Tame prices will be a relief to consumers, whose wages are growing at an even slower rate.

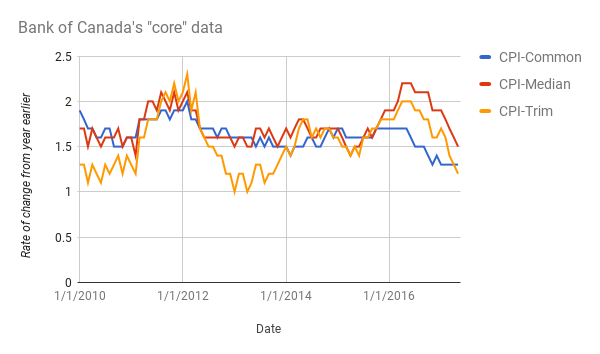

Glass half empty: There is a flip side to weak inflation. Consumers love it, but the companies that employ them—not so much. Canada’s GDP has been growing at annual rates in excess of three per cent since last autumn, but none of that growth is showing up in the inflation data. Key are the Bank of Canada’s three measures of core inflation. (For simplicity’s sake, the central bank names them CPI-trim, CPI-median, and CPI-common.) These gauges attempt to correct for the swings in the costs of items such as vegetables and gasoline. All three of those measures are trending away from the central bank’s two per cent target. They indicate economic weakness, not strength.

Also: something might be happening with the price of food. For the better part of a year, we’ve benefited from a vicious price war between Canada’s big grocers. StatsCan’s index of food prices has declined every month since October. But in May, the drop was only 0.1 per cent. That could signal a bottom. Dalhousie University, which publishes Canada’s Food Price Report, says StatsCan is behind the curve. Dalhousie’s Faculty of Management runs spot checks on grocery prices and publishes updated data and forecasts. The latest Food Price Report, published June 19, suggests meat prices have increased 11 per cent this year. By the end of 2017, Dalhousie forecasts that our groceries will be between three and four per cent more costly than they were at the start of the year.

Bottom line: Renters and home seekers in Toronto and Vancouver will protest, but inflation isn’t an issue for most of us. That means the Bank of Canada can wait before it starts its march to higher interest rates: watch for Bay Street’s expectations for the first increase to harden around policy meetings in September and October, rather than as soon as July. The weakness of core inflation is a puzzle, and it will give central bankers pause. But the U.S. Federal Reserve faced the same conundrum and it opted to start to raise interest rates. The Bank of Canada will do the same.

MORE ABOUT BANK OF CANADA:

- A national real estate crash isn’t in the cards

- Debt loads and soaring house prices a growing concern: Bank of Canada

- Hot real estate, high household debt create exposure to risk, says Bank of Canada

- Why Ottawa should bail out homebuyers if house prices tank

- The Bank of Canada interest rate decision shows Sunny Stephen is back

- Making sense of the economy’s mixed signals

- The risk of a financial crisis in Canada is growing

- Stephen Poloz’s journey from sunny to sour to so-so